James Robert Oxford, Department of Defense, Washington, D.C., USA

Introduction

U.S. Special Operations Command (USSOCOM) seeks to understand the relationship between special operations and the cyber domain. This research narrows the focus to a single Special Operations Forces (SOF) core function—foreign internal defense (FID)—by proposing a novel framework for cyber-FID. According to the Joint Staff’s Joint Publication (JP) 3-05, Special Operations, “FID refers to U.S. activities that support a host nation’s (HN) internal defense and development (IDAD) strategy and program, designed to protect against subversion, lawlessness, insurgency, terrorism, and other threats to its security and stability.”[1]

Importantly, SOF employs FID to protect U.S. interests in foreign competition and conflict environments—not through resource-intensive military force, but by defending forward to equip allied forces to address these threats. Furthermore, over the past few years, the U.S. government has engaged in cyber capacity-building efforts with many foreign partners and allies, yet the Department of Defense (DoD) lacks a formal structure to guide these initiatives. Creating a cyber-FID framework will enhance USSOCOM’s understanding of this core function’s relationship with cyber, contributing to the “operational art” of FID in shaping operations and providing a structure that can be integrated into planning and training activities. [2]

CONTACT James Robert Oxford | jamesroxford@gmail.com

The views expressed in this work are those of the author(s) and do not reflect the official policy or position of the United States Military Academy, the Department of the Army, or the Department of Defense. © 2024 Arizona Board of Regents/Arizona State University

This article first explores the need for a cyber-FID framework and highlights the importance of defining one now within the current geopolitical environment. It then provides a brief overview of traditional FID and examines the effectiveness of cyber-FID in countering state-on-state cyber threats. Finally, the article proposes a cyber-FID framework aligned with the three categories of traditional FID: indirect support, direct support (excluding combat operations), and U.S. combat operations. The article concludes with final thoughts on future research.

Problem Statement

Colonel Patrick Duggan (USA), a career Special Forces officer with cyber expertise, emphasized the importance of this topic in a 2015 Joint Force Quarterly article, stating, “Today’s global environment impels the United States to adopt cyber-enabled special warfare as a strategic tool of national military strategy.”[3] Colonel (Ret.) Duggan argues that Iran and Russia surpass the U.S. in the strategic use of cyber-enabled special warfare. He presents three concepts of operation (CONOPs) for closing this gap, including one for cyber-FID. Despite a handful of references to the cyber-FID concept, the current literature offers no clear description of what cyber-FID should or could entail. In fact, the nearly 200-page Joint Publication 3-22, Foreign Internal Defense, mentions the term cyber only three times.[4] Since FID is a core activity of special operations and cyber is a critical warfighting domain, USSOCOM needs a cyber-FID framework.[5]

Working with partners and allies is imperative to achieving U.S. and partner interests and is emphasized in many official government documents, including the National Security, Defense, and Military Strategies. This article is not the first to suggest that these efforts should extend into the cyber domain. In 2019, William Smith of the U.S. Marine Corps Communications and Information Systems Division proposed the creation of Cyber Engagement Teams (CETs) to “expand on current Foreign Internal Defense (FID), Security Force Assistance (SFA), or other cooperation and engagement apparatuses.” He explained that “working ‘by, with, and through’ friendly nations, [and by developing] lasting relationships, CETs are a logical tool to contend with cyber adversaries through friendly engagement, collective security, and partnering.”[6] To better align these concepts, Smith’s CET construct would benefit from a cyber-FID framework.

Before introducing the cyber-FID framework, this article will set the stage by outlining key concepts of traditional FID. First, two critical questions arise and merit discussion: Why create a cyber-FID framework? And why now?

The Need for a Cyber-FID Framework

“Foreign internal defense capability sets must increase capacity-building efforts in areas such as cyber.”[7]— James M. DePolo, Former Director of Special Operations, U.S. Army Special Warfare Center

USSOCOM needs a cyber-FID framework for three reasons. First, a cyber-FID framework will outline a consistent approach to cyber-FID, ensuring continuity across theaters of operation and creating a foundation for advancing cyber-FID theory and best practices. The framework will be flexible enough to adapt to specific partner needs while remaining structured enough to provide a common operating concept that operational and tactical teams can use as a starting point.

Second, publishing a cyber-FID framework will reassure allies and partners of the U.S. commitment to global cyber resiliency and contribute to the layered cyber deterrence advocated in the Cyberspace Solarium Commission report. [8] Smith notes that it will:

signal to adversaries the close ties between the U.S. and a friendly nation… working continually ‘by, with, and through’ our allies and partners would establish and maintain the necessary habitual relationship required for continued shaping and posturing of the environment, provide a level of deterrence, and may even prevent open conflict between adversaries.[9]

The 2014 Quadrennial Defense Review’s executive summary stated, “Building security globally not only assures allies and partners and builds partner capacity but also helps protect the homeland by deterring conflict and increasing stability.”[10] This connection between FID and deterrence is also relevant in the cyber domain.

Lastly, defining a cyber-FID framework will communicate the importance of these efforts in addressing the changing character of war and enrich the public conversation on conflict in the gray zone—a term often used to describe “competitive interactions among and within state and non-state actors that fall between the traditional war and peace duality.”[11] Most cyber operations fall within this category. In the 2016 USSOCOM White Paper from which this definition is drawn, the author briefly explores the opportunity for a new lexicon, suggesting that it would “help us understand and engage challenges in the gray zone better… [and] help yield better decisions.”[12] The cyber-FID framework presented in this article takes a step in that direction.

The Time for Cyber-FID Is Now

“Adapt Now, or Lose Later”[13] — General Mark A Milley, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff

It is helpful to consider an analogy to aviation FID. In his Spring 1997 Airpower Journal article, “Whither Aviation Foreign Internal Defense?” Wray Johnson wrote, “It is the identification of links between the past and present which enables us to comprehend our actions in context. In that light, the concept of aviation-centered FID is not original: it is a response to the void created in SOF FID capabilities following the Vietnam War.”[14] Johnson traces the history of aviation FID from its origins in “rudimentary counterinsurgency (COIN) doctrine” after the Second World War to its role in addressing the “low-intensity conflict” of post-Vietnam Central America, and ultimately to its formalization in Air Force Operational Doctrine in 1992. He makes the following salient point:

Although the Air Force nominally continued to perform the FID mission after Vietnam, it was as an adjunct to its conventional mission and was accomplished on an ad hoc basis. In other words, extant resources were tapped to perform FID activities. However, several studies had conclusively documented that ‘the lack of sustained, coordinated effort by individuals dedicated to the [aviation] FID mission is the principal reason we [AFSOC] have failed to achieve the long-term changes in the way developing countries support, sustain, and employ airpower.’[15]

Today, we see history beginning to repeat itself in the need to formalize cyber-FID.

Similar to aviation FID, this article argues that the concept of cyber-FID is not new; rather, it emerged from the void created in SOF FID operations toward the end of the Global War on Terror during the global shift to great power competition—particularly in the cyber domain.[16] It is at this critical inflection point, as the United States faces two cyber-capable superpowers and the character of war continues to evolve, that the nation must move beyond ad hoc efforts to achieve long-term, systemic changes in how developing countries support, sustain, and employ cyber defense capabilities. [17]

In his proposal to create Cyber Engagement Teams (CETs), Smith estimates that full implementation would likely take more than five years. He urges that a CET or similar construct be “incorporated at the earliest in all activities” because “cyber operations support and are complementary to all levels of war and warfighting functions.”[18]Thus, the time is now for a framework that can lead to a sustained, coordinated cyber-FID effort.

Unlike aviation FID, however, cyber-FID must account for the many unique challenges inherent in cyberspace. Cyber is now ubiquitous, reaching into all aspects of human society. Cyber threats are pervasive, and cyber actors range from individuals to nation-state-sponsored groups and everything in between. Aviation doctrine does not need to consider attribution and anonymity in the sky, and airspace and air capabilities do not evolve as rapidly as cyber does. Jurisdictional boundaries in cyberspace are not clearly defined, and even if they were, cyber actors frequently use infrastructure hop points between their command and control and their final target. These challenges, among many others, are unique to cyberspace. The cyber community continues to evolve and innovate to counter them effectively. A cyber-FID framework provides a tool to rapidly transfer these innovations to the host nation.

Literature Review

This article fills a gap in the current literature by proposing a new cyber-FID framework. In 2013, Colonel Brian Petit (USA, Ret.) made a seminal contribution to the Special Operations literature with his book Going Big by Getting Small, which examined the strategic use of SOF in peaceful, left-of-boom engagements. In the book’s foreword, Admiral Eric Olson (USN, Ret.) explains, “Much of the literature on special operations is dominated by headline-making missions: deep raids, harrowing firefights, close combat actions… yet there is another narrative on special operations [of strategic peacetime engagements] told less often and with greater difficulty.”[19] Although the former still dominates special operations literature, there is now a substantial body of work on special operations strategy, including Special Operations: Out of the Shadows, edited by Christopher Marsh et al.[20] There is also a growing body of literature on cyber strategy, such as Cyber Persistence Theory by Michael Fischerkeller and Cybersecurity and Cyberwar by P.W. Singer.[21]

However, literature on the intersection of cyber and special operations strategy remains limited. Most existing work consists of operational doctrine and contemporary news cases. Colonel (Ret.) Patrick Duggan wrote several articles on this topic between 2014 and 2016, Colonel the one referenced above. A few other works, such as Expanding the Menu: The Case for CYBERSOC by Benjamin Brown, argue for the creation of a cyber-SOF component and explore organizational design considerations. [22] Additionally, the article The Integration of Special Forces in Cyber Operations by LTC Jonas van Horen of the Netherlands Ministry of Defense examines, using the Netherlands as a case study, three roles in which SOF could support the cyber domain, as well as three potential models for a SOF-cyber organization. [23]

Methodology

Extensive academic research was conducted to determine whether a cyber-FID framework already exists—whether codified across multiple documents or referred to by a different name. Finding no such evidence, over a dozen SOF and/or cyber practitioners were interviewed to develop a deeper understanding of traditional FID and current capacity-building efforts in the cyber domain. Finally, leveraging personal cyber expertise and building on JP 3-22, this research proposes a new cyber-FID framework.

The Cyber-FID Framework

“I use the term ‘framework’ because it is less deterministic than a theory and not as prescriptive as a method. It is messy, full of contradictions, and much more art than science… There is nothing parsimonious about the cyber-FID framework I present.” [24] — Marko Papic, Author (modified quote)

This section begins with the doctrinal definition of traditional FID and a brief explanation. It then addresses common critiques encountered during the research process regarding why cyber-FID is the appropriate construct for countering today’s threat of future global power conflict. Finally, the section concludes by defining the cyber-FID framework.

An Overview of Traditional FID

The Joint Staff’s JP 3-22, Foreign Internal Defense, is a 200+ page publication detailing the FID mission. This article does not attempt to cover all aspects of JP 3-22 but instead establishes a baseline of traditional FID concepts as a foundation for exploring its extension into cyber-FID. From JP 3-22:

FID is the participation by civilian agencies and military forces of a government or international organization in any of the programs or activities taken by a host nation (HN) government to free and protect its society from subversion, lawlessness, insurgency, violent extremism, terrorism, and other threats to its security. The United States Government (USG) applies FID programs or operations within a whole-of-government approach to enhance the IDAD program of the HN by specifically focusing on an anticipated, growing, or existing internal threat.[25]

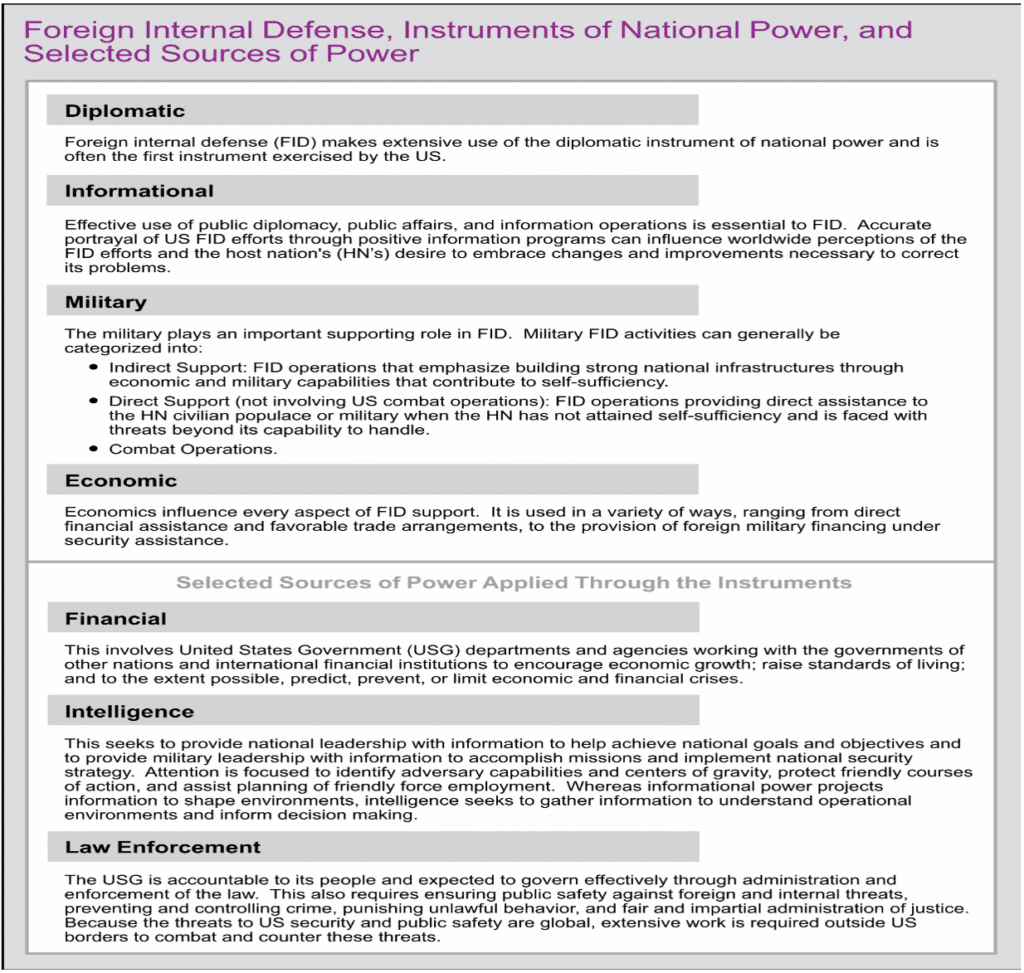

There are two key components to emphasize in this definition. First, FID is conducted to “enhance a HN’s IDAD program”—the sole purpose of FID should never be solely about U.S. objectives, though it should always align with U.S. interests. Second, FID requires a whole-of-government approach and is not solely the domain of SOF or even the Department of Defense (DoD). In fact, FID involves all instruments of national power, as illustrated in JP 3-22‘s Figure 1: FID Instruments and Sources of National Power. However, for simplicity, this article focuses exclusively on the military instrument.

Cyber FID and the State-on-State Threat

During the research for this article, practitioners held competing views on whether protecting against a state-on-state cyber threat truly falls under FID. Two main arguments suggest it does not.

The first argument centers on the stark contrast between traditional FID threats—terrorists, insurgents, and violent extremists—versus the stereotypical hackers in hoodies located somewhere in dark basements. However, as Mikko Hypponen highlights in his linux.com blog post, this stereotype obscures the significant threat posed by highly sophisticated, well-trained, and often state-funded cyber professionals.[26] Similarly, excluding cyber from the FID discussion simply because it operates in the digital rather than the physical realm would be a mistake, as modern conflicts increasingly span both physical and digital domains.

Figure 1 – FID Instruments and Sources of National Power[27]

The need for convergence between the cyber and physical domains—both in practice and in thought—is discussed in a Spring 2021 Military Review article by Maj. Anthony Formica, U.S. Army. He warns, “The United States has run out of time for developing approaches to compete in the cyber domain, and it must use the assets and forces currently available to prevent future strategic setbacks.”[28] Formica makes two key points. First, he concludes that the initial effects of future wars will occur in the digital information environment, as demonstrated by Russia’s annexation of Crimea. Second, he draws an analogy to Germany’s superior tank power in the Second World War, arguing that Russia has similarly embraced the cyber domain—adapting its entire concept of conflict around it—while the United States, in contrast, is slow-rolling convergence[29] and continuing “to focus on the men with guns and the tanks… and not on the host of hostile actions [in cyberspace] that precede them.”[30] Therefore, advancing the concept of cyber-FID is a necessary response to the growing cyber threat.

The second argument against classifying this as an FID problem focuses on the external nature of the threat, particularly within the context of great power competition. However, David Ucko addresses this concern in his article The Role and Limits of Special Operations in Strategic Competition:

In recent years, SOF has broadened its thinking on foreign internal defense (FID)… whereas FID traditionally meant aiding a friendly government against an insurgency, SOF now looks upon [FID] to boost a country’s ‘resilience’ against foreign-sponsored proxies, modes of disinformation, or political infiltration.[31]

This shift toward resilience is equally necessary in the cyber domain, which is not constrained by borders and serves as a primary medium for disinformation.

Bradenkamp and Grzegorzewski effectively argue in their 2021 Special Operations Journal article that Russia has long employed cyber gray zone tactics to wage unconventional warfare (UW), first in Estonia (2007), then Georgia (2008), and most recently in Ukraine (2014 and 2022).[32] The authors emphasize that Russia “used hackers, both native and foreign… to slow down [the defending] response to Russia’s conventional invasion… [and] could use virtual applications and proxy forces to have real-world effects.”[33] Not only do cyber operations have tangible implications for a country’s internal security, but Russia’s UW tactics and advance preparation of the battlefield allowed them to “quickly activate opposition groups within Ukraine to achieve strategic objectives before anyone could respond.”[34] Since cyber clearly poses a direct threat to a host nation’s internal security, advancing the concept of cyber-FID is both relevant and necessary.

Details of Traditional FID

“Although on the surface, FID appears to be a relatively simple concept, that appearance is deceptive; FID is [more] nuanced and complicated… often confused [with] training foreign forces, when in reality, there is much more to it.”[35] — Colonel (Ret.) John Mulbury, Army Special Operations Forces”

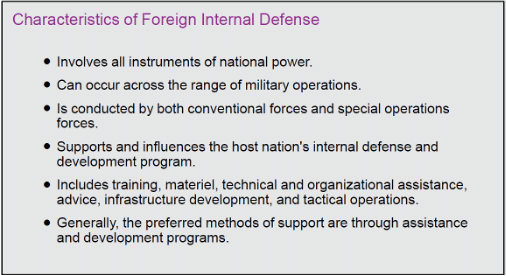

According to JP 3-22, as multi-domain transregional threats continue to grow, geographic combatant commanders rely on FID to “counter these threats in multiple countries, organized from an ideological credence [to support] each affected nation’s security.”[36] FID may take the form of a program, an operation, or a combination of both, integrated with interagency efforts as necessary and operating under the coordination of the U.S. embassy country team, as authorized by the Chief of Mission. Traditional FID falls into three categories, all requiring close coordination with interagency and international partners: direct support, indirect support, and U.S. combat operations. While FID is a core SOF function, it is not exclusively a military operation. Requiring a whole-of-government approach, it is also supported by conventional and multinational forces, as well as other U.S. Government (USG) departments and agencies.[37] The key characteristics of FID are illustrated in Figure

2 – Characteristics of Foreign Internal Defense.

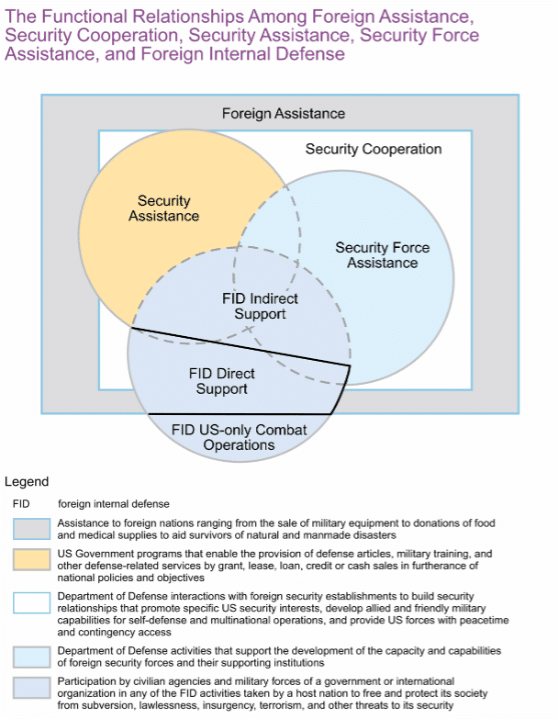

Figure 2 – Characteristics of Foreign Internal Defense[38]

It is important to define where FID sits in relation to several related concepts, as illustrated in Figure 3 – Functional Relationship of Concepts Related to FID. Security cooperation is fully encompassed within foreign assistance. As a broad term describing all DoD efforts to “develop foreign defense and security capabilities and build defense security relationships,”[39] security cooperation addresses the root causes of violent extremist organizations. It includes security assistance activities conducted under U.S. Code Title 22 (which covers diplomatic efforts) and forms a key element of FID by “providing many of the resources in the form of funding, materiel, and training.”[40] These efforts make up a significant portion of FID’s indirect support activities. Another major component of FID’s indirect support is security force assistance, which describes activities to “organize, train, equip, rebuild/build, advise, and assist” [41] foreign forces. Together, security cooperation and security force assistance provide the foundational support structure for FID operations.

Figure 3 – Functional Relationship of Concepts Related to FID[42]

FID also includes direct support activities short of combat operations. According to JP 3-22, direct support involves:

use of US forces to provide direct assistance to the HN civilian populace, or military. They differ from [security assistance] in that they are joint- or Service-funded, do not usually involve the transfer of arms and equipment, and do not usually (but may) include training local military forces. Direct support operations are normally conducted when the HN has not attained self-sufficiency and is faced with social, economic, or military threats beyond its capabilities to handle. Assistance normally focuses on civilian-military operations (primarily, the provision of services to the local populace), military information support operations (MISO), operations security (OPSEC), communications and intelligence cooperation, mobility, and logistics support. In some cases, training of the military and the provision of new equipment may be authorized.[43]

Notably, this section of JP 3-22 includes cybersecurity assistance as a component of direct support activities but does not provide details on what form this assistance might take. This article expands on that assistance, incorporating cyber’s role in all three categories of FID: indirect support, direct support, and U.S. combat operations, forming the foundation of the cyber-FID framework.

The final category of FID, U.S. combat operations, requires a Presidential decision to introduce U.S. combat forces as a temporary measure until host nation (HN) forces regain the capacity to conduct independent operations. These efforts typically take the form of one or more of the following: counterinsurgency (COIN), counterterrorism (CT), counter-drug (CD), or stabilization operations. [44]Importantly, the HN maintains overall responsibility and initiative for all U.S. FID operations to “preserve its legitimacy and ensure a lasting solution to the problem.” [45] Command and control in these operations is complex and requires “judicious and prudent rules of engagement” to maintain the perceived legitimacy and sovereignty of the HN government. [46]

According to JP 3-05, Special Operations:

FID operations are planned at the national and ministerial levels… in support of the HN IDAD strategy and in coordination with the [Chief of Mission],” who leads the overall FID effort. “FID planning is complex… FID planners must understand US foreign policy, focus to maintain or increase HN sovereignty and legitimacy, and understand the strategic implications and sustainability of US assistance to an HN… Military planning for unified action is essential to build unity of effort in the USG approach to FID.” [47]

The same principles apply to cyber-FID, reinforcing the need for cohesive, well-planned integration of cyber capabilities into the broader FID mission.

The Cyber-FID Framework

“We have learned that we cannot live alone in peace. We have learned that our own well-being is dependent on the well-being of other nations far away. We have learned to be citizens of the world, members of the human community”[48] — President Franklin Delano Roosevelt

This article now turns to the creation of the cyber-FID framework. The old adage that people are our greatest asset is particularly relevant in this context, as in all others. SOF are often best positioned for FID operations “due to their extensive language capability, cultural training, advising skills, and regional expertise.”[49] This applies to the cyber domain as well. As one Cyber National Mission Force (CNMF) officer observed during Hunt Forward operations in Ukraine: “[Ukrainian partners] will have a certain way of drawing a network object, and the terminology gap had to be beaten before we could proceed [with the operations].”[50] In addition to personnel, physical hardware is also necessary and may be obtained through host nation purchase or U.S. security assistance as part of the cyber-FID effort. As with other SOF initiatives, cyber-FID requires time to mature the HN cybersecurity posture and to achieve IDAD objectives through a whole-of-government, multi-stakeholder effort.

Figure 4 – The Cyber-FID Framework

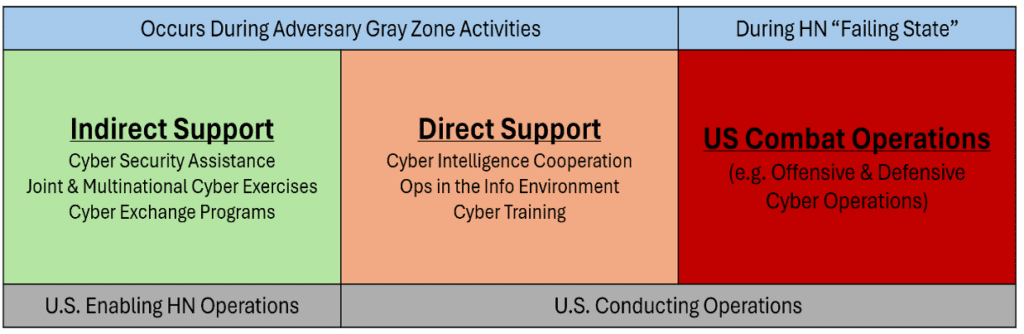

Summarized in Figure 4 – The Cyber-FID Framework, the framework is structured similarly to traditional FID, dividing operations into three categories: indirect support operations, direct support operations, and U.S. combat operations. As illustrated in blue across the top of the figure, indirect and direct support operations may take place during adversary gray zone activities, whereas U.S. combat operations can only occur when the host nation is in a failing state. Additionally, as shown in gray at the bottom of the figure, indirect support operations are solely intended to enable the HN, whereas U.S. forces may conduct operations on behalf of the HN as part of direct support or U.S. combat operations.

The following sections explore how the traditional FID categories outlined in JP 3-22 are adapted to the cyber context.

Indirect Support Operations

This category of cyber-FID focuses on providing equipment and training to enable the host nation (HN) to secure itself in cyberspace and conduct its own cyberspace operations (CO). It can be divided into three broad approaches, adapted from JP 3-22: (1) cyber security assistance, (2) joint and multinational cyber exercises, and (3) cyber exchange programs.[51]

The first approach, cybersecurity assistance, includes the provision of cyber equipment, training, and services to the HN. Cyber equipment may consist of computing and networking hardware for end users and national communications infrastructure. Unlike traditional FID, which covers mostly specialized defense articles, cyber-FID relies heavily on commercially available hardware, highlighting the crucial role of the private sector in cyber-FID operations. Cyber-FID efforts will train HN forces to conduct cyberspace operations, including network security operations and cyber threat hunting. Additionally, it will include “train the trainer” courses to teach HN personnel how to conduct future cyber training independently. Services encompass any: “service, test, inspection, repair, [or] training publication… used for the purpose of furnishing military [cyber] assistance… usually integrated with equipment support… to ensure the equipment is suitable for HN needs and the HN is capable of maintaining it.”[52]

The next approach, joint and multinational cyber exercises, “offer the advantage of training US forces while simultaneously increasing interoperability with HN forces.”[53] Since 2016, the NATO Cooperative Cyber Defense Centre of Excellence (CCDCOE) has hosted Crossed Swords, an annual cyber training exercise encompassing various cyber disciplines.[54] This complex exercise covers multiple geographic areas, involves critical information infrastructure providers, and integrates cyber-kinetic engagements,[55] drawing participation from over 100 experts across more than two dozen countries. According to the CCDCOE’s report from Crossed Swords 2020, “the focus is on advancing cyber Red Team members’ skills in preventing, detecting and responding to an adversary in the context of full-scale cyber operations.” The report goes on to explain, “the main task and lesson is to understand the coordination between multiple disciplines… link cyber elements with conventional force… [train] penetration testers, digital forensic professionals, and situational awareness experts.”[56] U.S. cyber-FID efforts would benefit greatly from participating in and/or organizing similar exercises, enhancing both HN capabilities and interoperability with U.S. and allied forces.

The final approach to indirect support operations is cyber exchange programs, which may occur at an individual or unit level. These programs serve to: “foster greater mutual understanding and familiarize each force with the operations of the other.”[57] As described in JP 3-22, commanders can maximize the benefits of exchange programs by combining them with joint and multinational exercises. For example, in a cyber exercise such as Crossed Swords, key cyber personnel could be exchanged to work alongside the partner nation’s cyber and conventional forces. This approach is likely to be far more effective for improving interoperability than exchanges conducted during routine operations

Direct Support Operations

Unlike indirect support operations, which focus on enhancing the host nation’s (HN) self-sufficiency, direct support operations involve U.S. forces actively conducting operations in support of the HN.[58] Under traditional FID, as discussed earlier, direct support is typically employed when the HN faces threats—such as ongoing kinetic attacks—beyond its ability to handle. [59] In the cyber domain, however, the threshold that shifts an HN’s FID need from indirect to direct support may be less clearly defined.

According to Formica, citing the 2017 National Security Strategy:

America’s rivals have ‘become skilled at operating below the threshold of military conflict… with hostile actions cloaked in deniability.’ Cyberspace operations… not only [set] the conditions for the employment of traditional forces but also [complement] their efforts by weaving a web of muddled facts and plausible deniability.[60]

By the time an adversary has set the conditions to employ traditional forces against the HN, the U.S. may have little time to respond. To protect against a fait accompli attack, such as Russia’s 2014 annexation of Crimea, direct support operations should be considered and conducted concurrently with indirect support operations. [61] Cyber-FID direct support can be categorized into three areas: (1) cyber intelligence cooperation, (2) operations in the information environment, and (3) cyber training.

The bedrock of any cyber operation, including cyber-FID, is intelligence. As stated in JP 3-22, the following principles apply to cyber-FID and cyber intelligence:

The sharing of US intelligence is a sensitive area that must be evaluated based on the circumstances of each situation. Cooperative intelligence liaisons between the US and HN are vital; however, disclosure of classified information to the HN or other multinational FID forces must be authorized. Generally, assistance must be provided in terms of evaluation, training, limited information exchange, and equipment support.”[62]

This assistance is tailored to the HN’s specific needs and capabilities, with the goal of helping the HN achieve self-sufficiency.

A notable example of cyber-FID intelligence cooperation, though not previously categorized as such, is USCYBERCOM’s Hunt Forward Operations (HFO). In December 2021, Lt. Gen. Hartman, then head of the Cyber National Mission Force (CNMF), discussed HFO deployments to Ukraine weeks before the Russian invasion. What was intended as a standard initial assessment before deploying the full CNMF team for the HFO was quickly deemed insufficient: “Instead of executing the normal plan, the team lead immediately got on the phone and asked to deploy the rest of the team, and we immediately went into a hunt operation.”[63] HFO are only conducted at the request of the HN, and it’s easy to see how these conditions, with the imminent threat of 130,000 Russian soldiers amassed on the border, would classify this as a cyber-FID direct support operation.

In an interview, Lt Gen Hartman described the way intelligence “fits in for [the CNMF] first and foremost,” stating that the CNMF “wants to execute an intelligence-driven mission.” He also highlighted the role of private-sector cyber intelligence, calling it “extraordinarily powerful” in helping U.S. cyber forces locate adversaries. According to Hartman, all cyber intelligence gathered during HFOs is shared directly with the HN. On the ground in Ukraine, whenever the CNMF found evidence of a Russian cyberattack, the team immediately shared the information with Ukrainian counterparts. This intelligence-sharing partnership has continued even after the U.S. team left. As of the interview, Hartman estimated that “we’ve shared over 6000 indicators of compromise… that’s all stuff we’ve been able to see from industry partnerships… from activity on the ground.”[64] HFOs are an established practice of cyber intelligence cooperation with host nations and fit perfectly within the cyber-FID direct support framework.

Formica described another example of cyber intelligence cooperation, which would be the bedrock of what he referred to as a convergence fusion cell. The fusion cell would deploy the right personnel, resources, and authorities to, for example, establish NATO Force Integration Units as an early warning of adversary convergence between cyber and physical domains

The primary mission of convergence fusion cells would be to combine intelligence from cyberspace and the information environment with developing events in the physical world to detect a fait accompli attack in its infancy and to have the ability to respond quickly enough to prevent the attack from being carried out.[65]

This intelligence cooperation model would broadly encompass multiple data streams across the U.S., HN, and regional intelligence and law enforcement agencies.

The second category of cyber-FID direct support is operations in the information environment.[66] Information is a main component of any military operation, and cyber-FID forces can leverage it to achieve national objectives in support of the HN Internal Defense and Development (IDAD) strategy. JP 3-22 lays out considerations for the role of Military Information Support Operations (MISO) in traditional FID, which also applies to cyber-FID direct support operations. As in traditional FID, MISO can be used for cyber-FID direct support operations to “gain, preserve, and strengthen civilian support for the HN government and its IDAD program,” and “build and maintain the morale of HN forces” in the face of cyberattack. [67] MISO can also be employed to persuade the adversary that cyberattacks will fail or will not be worth the cost to carry out. It can be used to “project a favorable image of the HN government and the US… inform the international community of US and HN intent and goodwill… [and] develop HN information capabilities.”

The final category of cyber-FID direct support operations is cyber training. According to JP 3-22, “the HN FID situation may intensify and increase the need for training beyond that of indirect support. Direct support operations should provide more immediate benefit to the HN and may be used in conjunction with various types of SA indirect support training.”[68] The illegal invasion of Ukraine and the associated Russian cyberattacks provide an example of conditions suitable for cyber-FID direct support cyber training. In an October 2023 article, the SOFREP News Team reported that Estonia and the European Union recently established a cyber classroom and military cyber facility in Kyiv, both designed to: “[prepare] Ukrainian specialists to defend against sophisticated cyberattacks and ensure the stability and functionality of the nation’s digital society during times of conflict.” Additionally, “the United States and Denmark announced a collaborative effort… [to] develop a skilled [Ukrainian] cybersecurity workforce.”[69] The article did not provide details on the specifics of the cyber training, but this effort could be better coordinated within the broader cyber-FID framework proposed in this article.

U.S. Combat Operations

Finally, according to JP 3-22: “U.S. participation in combat operations as part of a FID effort requires Presidential approval” and may occur if “the condition of the [HN]… descend[s] into a failing state.” More information about defensive and offensive cyberspace operations (CO) that may be conducted can be found in JP 3-12, Cyberspace Operations:

Cyberspace capabilities are integrated into the Joint Force Commander’s plans and synchronized with other operations across the range of military operations… Effective integration of CO with operations in the physical domains requires the active participation of CO planners and operators… in coordination with other USG departments and agencies and national leadership.[70]

Nothing in the unclassified literature suggests that Presidential approval was granted for Ukraine, or that the U.S. has participated in cyberspace operations associated with this conflict. However, such participation could be an option under the cyber-FID framework.

Conclusion

For USSOCOM, understanding the role of cyber in its FID mission is a crucial evolution in how the United States competes with its adversaries. The cyber-FID framework presented in this article provides a structured approach for U.S. forces, reassures allies and partners, and highlights the importance of cyber-FID efforts in addressing the changing character of war. As seen in the aviation FID case study examined earlier, the concepts of cyber-FID are not new—but formalizing them into a single framework is now necessary to compete and win in this era of great power competition.

The framework proposed in this article follows the same structure as traditional FID, divided into three main categories. First, indirect support operations, which include activities such as cybersecurity assistance, joint and multinational cyber exercises, and cyber exchange programs. Second, direct support operations, which encompasses cyber intelligence cooperation, operations in the information environment, and cyber training. Finally, U.S. combat operations, which require Presidential approval and may include offensive or defensive cyber operations.

This framework should be viewed as a starting point for the cyber-FID discussion. It needs to be debated, operationalized, and refined. The framework was developed from a single, biased, American perspective, so evolving it with input from the partners it is meant to support will be critical to its success. Additionally, this article does not address the current legal and policy constraints on cyber operations, how these constraints may shift in times of competition, crisis, or conflict, or their potential impact on cyber-FID—particularly regarding host nation consent and compliance. Clearly, these issues require further research.

Finally, while this article focuses on cyber-FID within the military instrument of power, it is important to recognize that FID extends across all instruments of power. Future work should examine the role of other DIME-FIL instruments and interagency partners in cyber-FID efforts—perhaps starting with the U.S. Department of State and its existing cyber capacity-building initiatives. Further, USSOCOM should explore how private sector activities—particularly recent efforts to support Ukraine[71]—could be incorporated into the cyber-FID model.

James Robert Oxford has been a civilian employee in the Department of Defense since 2010 and has held both technical and supervisory positions in operations, analysis, and cybersecurity. He holds a Master of Science in Strategic Information and Cyberspace Studies and a concentration in Strategic Leadership Studies from the National Defense University’s College of Information and Cyberspace.

[1] Joint Chiefs of Staff, Special Operations, JP 3-05 (Washington, DC: Joint Chiefs of Staff, 2020), II–10.

[2] Brian S. Petit, Going Big by Getting Small: The Application of Operational Art by Special Operations in Phase Zero (Parker, CO: Outskirts Press, 2013).

[3] Patrick Duggan, “Strategic Development of Special Warfare in Cyberspace,” National Defense University Press, October 1, 2015, https://ndupress.ndu.edu/Media/News/News-Article-View/Article/621123/strategic-development-of-special-warfare-in-cyberspace/.

[4] Joint Chiefs of Staff, Foreign Internal Defense, JP 3-22 (Washington, DC: Joint Chiefs of Staff, 2018), https://www.jcs.mil/Portals/36/Documents/Doctrine/pubs/jp3_22.pdf.

[5] Joint Chiefs of Staff, Special Operations, II–4.

[6] William R. Smith, “Bytes, With, and Through: Establishment of Cyber Engagement Teams to Enable Collective Security.,” Special Operations Journal 5, no. 2 (July 1, 2019): 151, https://doi.org/10.1080/23296151.2019.1658056.

[7] James M. DePolo, “Foreign Internal Defense and Security Force Assistance,” in Special Operations: Out of the Shadows, ed. Christopher Marsh, James D. Kiras, and Patricia J. Blocksome (Boulder, Colorado: Lynne Rienner Publishers, 2019), 164.

[8] Cyberspace Solarium Commission, “Final Report,” March 2020, https://www.solarium.gov/report.

[9] Smith, “Cyber Engagement Teams,” 154.

[10] U.S. Department of Defense, 2014 Quadrennial Defense Review (Washington, DC, 2014), V–VI, https://dod.defense.gov/Portals/1/features/defenseReviews/QDR/2014_Quadrennial_Defense_Review.pdf.

[11] U.S. Special Operations Command, “White Paper: The Gray Zone,” September 9, 2015, 1, https://publicintelligence.net/ussocom-gray-zones/.

[12] U.S. Special Operations Command, 8.

[13] Mark A. Milley, National Military Strategy of the United States of America (Washington, DC: Joint Chiefs of Staff, 2022), 1, https://www.jcs.mil/Portals/36/NMS%202022%20_%20Signed.pdf.

[14] Wray R. Johnson, “Whither Aviation Foreign Internal Defense?,” Airpower Journal, March 1, 1997, 2–3, https://archive.org/details/DTIC_ADA360614.

[15] Johnson, 5. This author quotes from a third source that could not be located and was cited as follows: “AFSOC Foreign Internal Defense (FID) Capability,” position paper, 25 November 1991.

[16] See: Laura Jones, “The Future of Warfare Is Irregular,” Fletcher Forum of World Affairs, July 1, 2022, https://static1.squarespace.com/static/579fc2ad725e253a86230610/t/633fae96d4791b16affa5288/1665117846643/Jones-2a_APPROVED.pdf.

[17] Milley, National Military Strategy of the United States of America, 1.

[18] Smith, 161.

[19] Eric Olson. Forward to Going Big by Getting Small: The Application of Operational Art by Special Operations in Phase Zero, by Brian Petit. (Parker, CO: Outskirts Press, 2013), iii-iv.

[20] Christopher Marsh, James D. Kiras, and Patricia J. Blocksome, eds., Special Operations: Out of the Shadows (Boulder, Colorado: Lynne Rienner Publishers, 2019).

[21] P. W. Singer, Cybersecurity and Cyberwar: What Everyone Needs to Know (Oxford University Press, 2014).

[22] Benjamin Brown, “Expanding the Menu: The Case for CYBERSOC,” Small Wars Journal, January 5, 2018, https://smallwarsjournal.com/jrnl/art/expanding-menu-case-cybersoc.

[23] Jonas van Hooren, “The Integration of Special Forces in Cyber Operations,” 2022, https://nps.edu/documents/110773463/135759179/The+Integration+of+Special+Forces+in+Cyber+Operations.pdf.

[24] Marko Papic, Geopolitical Alpha: An Investment Framework for Predicting the Future (Hoboken, New Jersey: Wiley, 2020), 3. The original quote: “there is nothing parsimonious about the constraint framework I present.” I liked how the author described the term ‘framework,’ so I modified the quote to apply to cyber-FID.

[25] Joint Chiefs of Staff, Foreign Internal Defense, ix.

[26] Mikko Hypponen, “Real Hackers Don’t Wear Hoodies: Cybercrime Is Big Business,” Linux.Com (blog), June 8, 2016, https://www.linux.com/news/real-hackers-dont-wear-hoodies-cybercrime-big-business/.

[27] Source: Joint Chiefs of Staff, Foreign Internal Defense, I–9.

[28] Anthony M. Formica, “From Cambrai to Cyberspace: How the U.S. Military Can Achieve Convergence between the Cyber and Physical Domains,” Military Review (U.S. Army CGSC, March 1, 2021), 101, Gale Academic OneFile.

[29] Formica, 103.

[30] Formica, 106.

[31] David H Ucko, “The Role and Limits of Special Operations in Strategic Competition: The Right Force for the Right Mission.,” RUSI Journal: Royal United Services Institute for Defence Studies 168, no. 3 (May 1, 2023): 12, https://doi.org/10.1080/03071847.2023.2219701.

[32] Nicholas Bredenkamp and Mark Grzegorzewski, “Supporting Resistance Movements in Cyberspace,” Special Operations Journal 7, no. 1 (January 2, 2021): 17–28, https://doi.org/10.1080/23296151.2021.1904570.

[33] Bredenkamp and Grzegorzewski, 23.

[34] Bredenkamp and Grzegorzewski, 23.

[35] Joint Chiefs of Staff, Foreign Internal Defense, I–1.

[36] Joint Chiefs of Staff, I–1.

[37] Joint Chiefs of Staff, I-1-I–3.

[38] Source: Joint Chiefs of Staff, I–8.

[39] Joint Chiefs of Staff, I–14.

[40] Joint Chiefs of Staff, I–16.

[41] Joint Chiefs of Staff, xxii.

[42] Source: Joint Chiefs of Staff, I–15.

[43] Joint Chiefs of Staff, I–18.

[44] Joint Chiefs of Staff, I–24.

[45] Joint Chiefs of Staff, I–25.

[46] Joint Chiefs of Staff, I–25.

[47] Joint Chiefs of Staff, Special Operations, II–11.

[48] Quoted by: E. John Teichert, “The Building Partner Capacity Imperative,” DISAM Journal of International Security Assistance Management (Defense Institute of Security Assistance Management, August 1, 2009), https://www.proquest.com/docview/197766575.

[49] Joint Chiefs of Staff, Foreign Internal Defense, xviii.

[50] Ryan, interview by Dina Temple-Raston, “Exclusive: Inside an American Hunt Forward Operation in Ukraine,” June 20, 2023, in Click Here, produced by Recorded Future News, podcast, loc. 12:42-53, accessed May 10, 2024, https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/72-exclusive-inside-an-american-hunt-forward/id1225077306?i=1000617669131.

[51] Joint Chiefs of Staff, Foreign Internal Defense, chap. VI sec. B “Indirect Support.”

[52] Joint Chiefs of Staff, VI–10.

[53] Joint Chiefs of Staff, VI–12.

[54] NATO Cooperative Cyber Defense Centre of Excellence, “Crossed Swords,” CCDCOE, accessed March 15, 2024, https://ccdcoe.org/exercises/crossed-swords/. According to the CCDCOE website, “recent iterations” have been jointly organized with CERT.LV which is the national cyber incident response institution of the Republic of Latvia.

[55] NATO Cooperative Cyber Defense Centre of Excellence. No US participation in this exercise could be found.

[56] NATO Cooperative Cyber Defense Centre of Excellence, “Exercise Crossed Swords 2020 Reached New Levels of Multinational and Interdisciplinary Cooperation,” CCDCOE, accessed March 15, 2024, https://ccdcoe.org/news/2020/exercise-crossed-swords-2020-reached-new-levels-of-multinational-and-interdisciplinary-cooperation/.

[57] Joint Chiefs of Staff, Foreign Internal Defense, VI–13.

[58] Joint Chiefs of Staff, VI–13.

[59] Joint Chiefs of Staff, chap. VI sec. C “Direct Support (Not Involving United States Combat Operations).”

[60] Formica, “From Cambrai to Cyberspace,” 104.

[61] Formica, 104.

[62] Joint Chiefs of Staff, Foreign Internal Defense, VI–27.

[63] Dina Temple-Raston, “Q&A With Gen. Hartman: ‘There Are Always Hunt Forward Teams Deployed,’” The Record, June 20, 2023, https://therecord.media/maj-gen-william-hartman-interview-ukraine-russia-click-here.

[64] Temple-Raston.

[65] Formica, “From Cambrai to Cyberspace,” 107.

[66] For more information see: U.S. Department of Defense, Strategy for Operations in the Information Environment (Washington, DC, 2023), https://media.defense.gov/2023/Nov/17/2003342901/-1/-1/1/2023-DEPARTMENT-OF-DEFENSE-STRATEGY-FOR-OPERATIONS-IN-THE-INFORMATION-ENVIRONMENT.PDF.

[67] Joint Chiefs of Staff, Foreign Internal Defense, VI–21.

[68] Joint Chiefs of Staff, VI–23.

[69] SOFREP News Team, “Ukraine Enhances Cyber Defense with New Training Facility,” October 13, 2023, https://sofrep.com/news/ukraine-enhances-cyber-defense-with-new-training-facility/.

[70] Joint Chiefs of Staff, Cyberspace Operations, JP 3-12 (Washington, DC: Joint Chiefs of Staff, 2018), I–8.

[71] For example, see the work done by the Cyber Defense Assistance Collaborative, which “came together to provide operational czyber defense assistance to Ukraine during the 2022 Russian invasion.” (https://crdfglobal-cdac.org/) How can USSOCOM leverage similar processes to respond to future crises?