In 2018, Maria Butina, a covert Russian agent, was arrested in the United States after infiltrating political and ideological networks tied to the presidential administration. Her mission was not traditional espionage but rather to gain influence—cultivating relationships and shaping narratives to align American discourse with Russian interests.[i] Her case revived an older, more elusive threat: the agent of influence. These strategically embedded individuals subtly reshape public opinion within a target society to serve a foreign power’s goal.[ii] Agents of influence have played a particular role within communist societies, where the aim is to ideologically subvert a non-socialist foreign nation and incite revolution.[iii]

CONTACT Douglas Wilbur | douglas_wilbur@yahoo.com

The views expressed in this publication are entirely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views, policy, or position of Arizona State University. © 2025 Arizona Board of Regents / Arizona State University

Operating covertly in the cognitive domain, agents of influence co-opt existing values, divisions, and sympathies through trusted roles in journalism, academia, diplomacy, and civil society. As irregular warfare evolves, the role of information warfare will only become more salient. Open democratic societies, lacking centralized controls and gatekeeping mechanisms, remain especially vulnerable to these tactics.[iv] The survival of these agents depends on plausible deniability and cumulative psychological effects. Measuring impact on public opinion is difficult enough; covert attempts at influence muddy the waters further.[v] The question remains: do agents of influence actually achieve tangible results? How dangerous are they to an open democratic society? The answer to this research problem may lie in a case study of a Vietnamese communist agent of influence during the Vietnam War.

The Perfect Influence Agent

Pham Xuan An was a South Vietnamese communist spy and influence agent who primarily worked for Time magazine while freelancing for other news outlets as a journalist. He served as a fixer and trusted assistant to many prominent American journalists working in South Vietnam.[vi] An graduated with an associate’s degree in journalism from Orange Coast College in California and was fluent in English. He was recognized by American journalists as the go-to expert on Vietnam and the war. Eminent journalist David Halberstam said, “[An] was the most trusted Vietnamese in the press corps. If An said it, it had to be true.”[vii] An’s American biographers and apologists argue that he was not an agent of influence, just a spy, because he never lied or spread disinformation to his American colleagues. However, this interpretation overlooks a key reality: information warfare and propaganda do not require deception or disinformation. In fact, disinformation poses a significant liability if the lie is discovered. The most effective propagandists avoid lying—something that, in An’s case, would have threatened his survival.[viii]

An’s role as a journalist and his close personal relationships with American colleagues put him in an excellent position to spy. However, his real power lay in his ability to shape how those colleagues thought about the war by framing it for them. He stated, “I always tried to tell the truth. But I used the truth in such a skillful way that no one could complain. That’s how you do it. Truth was a weapon, and I used it to my best advantage.”[ix] An explained how he handled inconvenient information: “I never lied in my reports. I simply left out the parts that would hurt the revolution. That’s not lying. That’s editing.”[x] This can be explained through a number of theoretical frameworks and established social influence techniques. For example, An employed the social proof technique, where colleagues looked to him, and other knowledgeable people they trusted, for cues on how to interpret ambiguous situations or make decisions.[xi] Thus, it is clear that An was an agent of influence. But how successful was he?

The Vietnamese communist leadership understood that eroding the American will to fight was the key to their victory. According to North Vietnam’s Prime Minister Pham Van Dong, “We need not defeat the Americans militarily in Vietnam. It is sufficient to break their will to continue. That war is fought in their newspapers and their streets.”[xii] An, then, would have sought victory in the information domain by influencing journalists.

This project aims to determine whether An’s influence on American journalists manifested in Time magazine’s news coverage of the conflict. Specifically, it examines whether the themes, metaphors, and frames found in Vietnamese communist propaganda can also be found—knowingly or not—in Time’s coverage of the war. In doing so, it asks a deeper question: can a single well-placed agent of influence shift the discourse of an entire nation?

Literature Review

There are a couple of research articles that examine Time’s coverage of Vietnam.[xiii]John Newhagen found that Time exhibited a pro-war bias in 1967, adopted a neutral stance in 1968, and shifted to a more critical perspective from 1969 through 1974. The thesis suggests that, during the later years, some articles may have misrepresented events in ways that aligned with anti-war sentiments. This could reflect An’s influence, or it might simply mirror broader trends that were already emerging. William Hammond explored how structural constraints, such as editorial pressures and ethical dilemmas, shaped reporting. Time’s reporters faced limited access, ambiguous information, censorship efforts, and the high personal risk of field reporting in a war.[xiv] Journalists clearly operated in a high-stress, high-risk environment that made both reporting and analysis especially difficult.[xv]

Communist Conceptions of Agents of Influence

Agents of influence can be defined as individuals covertly serving a foreign entity within their society from a position with access and ability to influence public opinion or decision-making that benefits the foreign entity.[xvi] In communist strategic doctrine, particularly in Soviet and Vietnamese models, agents of influence were conceptualized as integrated irregular warfare assets. Their task was to covertly operate within the ideological, cultural, or media ecosystems of rival societies. Their purpose was to infiltrate positions of discursive authority and reshape narratives, beliefs, and perceived realities in ways that would erode the adversary’s political will and delegitimize its institutions over time.[xvii] A narrative can be defined as a structured representation of events and characters that convey meaning by organizing experiences into a coherent, interpretable form. Narratives provide cognitive frameworks that guide how individuals interpret information, attribute causality, and make moral evaluations.[xviii] This reflects the broader Leninist view that ideological struggle is a terrain of warfare in itself—and that winning the war of ideas, particularly inside the enemy’s society, is as vital as winning on the battlefield.[xix]

The Soviets institutionalized Lenin’s conceptualization through their active measures doctrine, which explicitly defined agents of influence as individuals who could “penetrate and manipulate foreign media, parliaments, academic communities, and religious institutions.”[xx] These agents, often holding legitimate professional credentials, were not expected to lie outright but to subtly frame issues, promote division, and amplify existing doubts or contradictions. This is in keeping with the Marxist-Leninist understanding of contradiction as a tool of dialectical destabilization.[xxi] North Vietnam’s Central Propaganda Department trained operatives not only in ideological doctrine but also in Western rhetorical strategies and influence techniques. For example, they studied Western journalism to enhance their effectiveness with foreign journalists and NGOs. These agents were expected to speak the language—both literally and metaphorically—of Western liberalism. This knowledge helped them gain access to intellectual elites and media platforms from which they could shape dominant narrative.[xxii] They also had to manage what Marxists refer to as internal contradictions. As An put it, “I was a spy, yes, but I was also a journalist. Both jobs were the same: to understand, to explain, to influence.”[xxiii] Yet he also said, “I was able to read documents and attend press briefings. I gave the information to the revolution, and I gave a clean version to Time. The trick was knowing how to use each one.”[xxiv] And he insisted, “I never lied to anyone. I gave the same political analyses to Time that I gave to Ho Chi Minh.”[xxv] Success in his work and securing his survival depended on managing the contradictions of Western journalism and the imperatives of information warfare.[xxvi]

Framing and Strategic Truth Telling

An’s own words show that he avoided outright deception or fabrication by using a tactic best described as strategic truth-telling within the framework of framing theory. Through omission, selective emphasis, and credibility, he framed the war in ways that reinforced communist narratives and undermined American resolve. Framing elevates certain facts while omitting others to guide perception in ways that serve strategic objectives.[xxvii] One fictional example of framing, based on a historical operation, illustrates how An might have framed a military action for American journalists:

In the shadow of the Iron Triangle, U.S. helicopters thundered across once-quiet rice fields, and entire hamlets were evacuated ‘for their protection.’ Villagers watched as their ancestral homes were burned, not by the communists, but by American forces wielding napalm and bulldozers. While U.S. officials called it ‘pacification,’ to the people of Ben Suc, it felt like punishment. ‘Why must we suffer for politics we do not understand?’ one old woman asked.[SS1]

This passage exemplifies strategic truth-telling through narrative framing. It presents factually accurate details—U.S. helicopters, civilian evacuations, use of napalm and bulldozers, and official terminology like “pacification”—but does so in a way that guides readers toward a morally charged, emotionally resonant interpretation. Rather than falsifying events, the account emphasizes civilian suffering, displacement, and the dissonance between official language and lived experience.[xxviii]

Determining whether Time magazine reflected themes found in Vietnamese communist propaganda is not merely a matter of identifying narrative convergence; it is a question of understanding potential audience impact. Narrative convergence refers to the alignment of rhetorical, thematic, or ideological elements across distinct texts, institutions, or platforms, highlighting how seemingly independent discourses may reflect shared interpretive structures, whether through coordinated influence or parallel meaning-making.[xxix] Decades of research in political communication and media psychology show that audiences actively interpret messages through cognitive shortcuts, including framing cues, moral evaluations, and emotional salience.[xxx] For example, if a reader encountered a headline like “U.S. Bombs Viet Cong Stronghold in Strategic Victory,” the brain would quickly extract meaning from the embedded framing. Words like “stronghold” and “strategic victory” frame the event as militarily necessary and morally justified, activating schemas of security, patriotism, and success. This primes the reader to interpret further details through a lens of legitimacy and purpose.[xxxi]

If Time adopted frames that foregrounded U.S. moral ambiguity, civilian victimhood, or the inevitability of withdrawal—frames also present in Vietnamese communist messaging—then those stories may have done more than inform the public; they may have shaped the cognitive and emotional terrain of the Vietnam War debate. In this sense, framing is not merely a stylistic choice but a mechanism of influence that can affect public attitudes and democratic decision-making.[xxxii]

Journalists as Agents of Social and Cognitive Influence

In liberal democracies, journalists have traditionally occupied a unique position as mediators of public knowledge, though in today’s information environment, that role is rapidly changing. In the 1960s, however, journalists shaped not only what the public knew but also how people interpreted and morally evaluated unfolding events. They served as gatekeepers, interpreters, and framing agents whose choices helped construct reality in public discourse.[xxxiii] One illustrative case is that of Richard Gott, a senior journalist at The Guardian, who was revealed in the 1990s to have maintained a covert quid pro quo relationship with the Soviet KGB during the Cold War. Rather than fabricating stories, Gott amplified anti-imperialist frames and Cold War skepticism that aligned with Soviet ideological goals.[xxxiv] He used his editorial voice to launder adversarial perspectives into the British mainstream. Like Pham Xuan An, Gott operated within the media institution itself—not as an outsider—and influenced discourse not through outright deception, but through strategic framing and selective emphasis, leveraging his professional credibility to carry state-aligned narratives under the guise of independent journalism.[xxxv]

In the context of information warfare, journalists can function as vectors of cognitive influence. A vector, in military and epidemiological terms, is a vehicle that carries something, such as ideas, without originating it. Vectors enable the delivery, amplification, and integration of ideas into the host system. They create pathways for transmitting narratives, frames, and psychological cues into the target population’s information environment. In operational terms, the journalist becomes a narrative relay node, particularly vulnerable in contested environments where access is constrained and local intermediaries shape what they see and understand.[xxxvi]

In contemporary terms, new media technologies have disabled journalists’ exclusive ability to vector ideas. However, during the Vietnam war, trusted informants like Pham Xuan An, exerted powerful gatekeeping abilities. Deliberately embedded within the journalistic vector, An shaped not only what got reported but also how events were morally and causally interpreted. This was a form of indirect fire in the cognitive domain, achieving psychological effects through carefully calibrated, credible, and truthful-seeming narratives that bypassed overt propaganda filters. The journalist, in this case, became an unwitting force multiplier for adversarial influence precisely because the messages they carried benefited from perceived neutrality and institutional trust.[xxxvii]

War Journalism and Source Dependency

War reporting is arguably the most difficult and dangerous domain of journalism. It presents unique challenges that often undermine the journalist’s ideal of independence. Access to sources, documents, and events is constrained by language and cultural barriers. Reporters frequently depend on local informants, fixers, translators, and stringers to interpret both the physical and cultural terrain.[xxxviii] As a result, these local actors can become gatekeepers of meaning—shaping not only what journalists see and hear, but also how they understand, frame, and prioritize events.[xxxix]

Source dependency is particularly acute in asymmetrical or insurgency-based conflicts like the Vietnam War. Foreign journalists, especially early in the war, often lacked embedded status with U.S. military units. Urban-based reporters rarely had firsthand access to combat zones.[xl] Instead, they relied on local insiders fluent in both language and narrative—individuals who could navigate the conflict’s ideological complexities and provide context that shaped the reporter’s interpretive frame.[xli] In this information ecosystem, trusted sources could act as epistemic authorities, subtly guiding which stories were covered and how they were told.

A clear example of source dependency comes from Pham Xuan An’s role as a narrative intermediary during the 1963 Battle of Ap Bac, where Viet Cong forces faced superior Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) units. The Viet Cong held their ground, an outcome An framed for American journalists as a sign of communist resilience and South Vietnamese weakness. He highlighted real tactical failures, poor coordination, delayed reinforcements, and ARVN reluctance to advance as evidence of incompetence and low morale. By contrast, he emphasized the discipline and effectiveness of the Viet Cong, portraying their survival as a symbol of resistance and legitimacy. The resulting coverage helped seed early doubts in the American press, demonstrating how a trusted local source could subtly recalibrate foreign perceptions of the war.[xlii]

Narrative Convergence

To assess whether Time magazine reflected themes found in Vietnamese communist propaganda, this study applies the concept of narrative convergence. Narrative convergence refers to the extent to which distinct sources—possibly operating under different intentions—produce similar thematic, rhetorical, or moral representations of key events. It serves as a methodological lens for detecting and describing the overlap between Time’s reporting and Vietnamese communist propaganda. While overt alignment is rare, covert influence strategies, particularly those involving trusted intermediaries, can result in overlapping frames and parallel narratives, even without direct coordination.[xliii]

Narrative convergence can be measured through several research methods. One approach is to identify rhetorical markers, such as emotionally charged metaphors, appeals to moral outrage, or dichotomous constructions like “oppressor vs. victim.”[xliv] In media framing analysis, convergence is assessed through frame identification and frequency comparison, examining how different sources define problems, assign responsibility, and propose solutions.[xlv] In communication science, scholars have applied techniques like topic modeling, sentiment analysis, and lexical similarity metrics to quantify thematic overlap across corpora, especially in comparative political or wartime media research.[xlvi]

In this study, coding for narrative convergence involves identifying instances where Time magazine articles reflect themes, frames, or rhetorical strategies found in Vietnamese communist propaganda. For example, a hypothetical article influenced by An might describe a U.S. pacification campaign as leaving “scorched fields and orphaned children,” framing the war as punishment rather than liberation. If a propaganda document similarly portrays U.S. actions as imperialist cruelty, the two sources are coded as converging. Convergence is determined by shared moral framing, emotional salience, and interpretive alignment, not identical wording.[xlvii] This approach helps capture how An’s strategic truth-telling, through selective emphasis and framing, may have aligned Time’s reporting with North Vietnamese messaging.

Research Questions

The preceding review establishes that agents of influence like Pham Xuan An operated within vulnerable discursive ecosystems such as war journalism, using strategic truth-telling and narrative framing to shape Western understanding of the Vietnam War. Given the known mechanisms of source dependence, rhetorical convergence, and framing effects on public opinion, the following research questions guide this study’s empirical investigation of whether—and how—Time magazine’s coverage reflected ideological themes consistent with North Vietnamese propaganda:

Research Question One: To what extent do the thematic frames and rhetorical devices found in Vietnamese communist propaganda appear in Time magazine’s coverage of the Vietnam War during Pham Xuan An’s tenure?

Research Question Two: How frequently, and in what rhetorical functions, do emotionally resonant frames (e.g., civilian victimhood, moral ambiguity, the psychological toll of war) appear in Time’s Vietnam War coverage, and how do these align with communist propaganda objectives?

Research Question Three: To what extent does Time’s coverage of the Vietnam War incorporate oppositional or subversive framing patterns consistent with North Vietnamese propaganda goals?

Methods

This project employs a convergent mixed methods design to examine whether Time magazine’s coverage of the Vietnam War during Pham Xuan An’s tenure reflects themes and rhetorical strategies consistent with Vietnamese communist propaganda. This approach is well suited to complex communication phenomena where both measurable patterns and interpretive nuance are analytically significant. Quantitative content analysis allows for systematic, replicable measurement of rhetorical convergence, capturing the frequency, distribution, and statistical significance of narrative features across large textual corpora.[xlviii] Complementing this, qualitative rhetorical comparison offers contextual and discursive insight into how frames are constructed, morally positioned, and emotionally mobilized within specific historical and cultural settings.[xlix] The convergent design is particularly appropriate when neither method alone can fully capture the phenomenon of interest.[l] It enables the researcher to triangulate findings—using numerical data to identify patterns, and interpretive methods to explain their meaning—producing a richer, more valid understanding of strategic narrative alignment and potential influence operations.

Sources

Two data sets were used in this project. The first was a propaganda document dataset (N = 50), consisting of captured North Vietnamese and National Liberation Front propaganda materials drawn from the Texas Tech Vietnam Center & Archive. These documents were either untranslated (with Google Translate used for preliminary translation) or accompanied by official English translations prepared by Vietnamese translators working for the U.S. government. Documents were selected based on their discussion of propaganda strategy and ideological concepts. The second dataset comprised (N = 245) randomly selected Time magazine articles on the Vietnam War, published between 1965 and 1975. These were sourced from the Time archives on EBSCOhost. Articles focused solely on the U.S. anti-war movement or domestic politics were excluded, as An is unlikely to have influenced that coverage. Time articles from this period were published under institutional voice, meaning authorship was anonymous; therefore, texts cannot be parsed by author for a more specific analysis of individual influence. All articles and documents were transcribed using optical character recognition (OCR) software to convert scanned images of printed or typewritten material into machine-readable text.[li]

Data Analysis

Quantitative Analysis

Texts were processed using Natural Language Processing (NLP) techniques to quantitatively code rhetorical features across Time magazine articles and Vietnamese propaganda documents. After OCR conversion, TF-IDF (Term Frequency-Inverse Document Frequency) vectorization identified high-salience terms, while sentiment analysis flagged emotionally charged language consistent with propaganda themes. Cosine similarity scores were then used to compare thematic alignment between Time articles and propaganda documents. This approach enabled efficient detection of candidate texts for manual coding, ensuring consistency, scalability, and empirical grounding in the identification of narrative convergence.[lii]

Qualitative Analysis

The data was explored qualitatively through deductive, human-led systematic coding. Predefined categories—including key terms (e.g., imperialism, puppet government), metaphors, and other communication devices rooted in theoretical frameworks—guided the process. Manual coding identified the presence of rhetorical features such as moral framing and emotional appeals. The analysis began with the propaganda documents, which informed the codebook used for coding Time magazine articles. Unlike automated NLP tools, manual coding allowed for context-sensitive interpretation, particularly in evaluating tone, implied meaning, or narrative nuance that might elude machine classifiers. Two coders used a shared codebook and achieved strong intercoder reliability (Cohen’s Kappa > 0.82) on a 20% subsample of the propaganda documents, and (Cohen’s Kappa > 0.86) on a 20% subsample of the Time articles.

Mixed Methods Integration

Integration of quantitative and qualitative findings in this mixed methods design was conducted in parallel and then combined to deepen understanding of potential narrative convergence. Quantitative results—such as elevated cosine similarity scores, frequent use of emotional language, or alignment in high-salience terms—identified candidate articles for deeper rhetorical inspection. A total of n = 40 Time articles were selected using a matrix sampling strategy that accounted for high vs. low similarity, high vs. low sentiment, and historical time frame (early war: 1965–1967; late war: 1972–1975). These articles were then subjected to qualitative manual coding, where interpretive nuance, context, and strategic framing were assessed.[liii] Findings were integrated during analysis and interpretation: instances where both methods aligned were treated as strong convergence, while discrepancies prompted closer review of contextual or rhetorical divergences. This integration enhances validity and explanatory depth, ensuring that empirical patterns are supported by theoretically informed interpretation.[liv]

Statistical Analysis

Several statistical techniques were employed to assess the degree of narrative convergence between Time magazine articles and Vietnamese propaganda documents. Correlation and regression analyses were conducted alongside natural language processing tools. First, TF-IDF vectorization was applied to generate document-level term profiles.[lv] These profiles were compared using cosine similarity, producing a continuous measure of lexical and thematic alignment. To explore the relationship between convergence and specific rhetorical features (e.g., emotional tone, moral framing, strategic themes), point-biserial correlations were calculated between cosine similarity scores and binary-coded variables.[lvi] This approach enabled assessment of whether articles reflecting certain rhetorical strategies were more likely to align with propaganda narratives.

Next, multiple linear regression models were constructed to predict convergence scores based on the presence of rhetorical variables. These models tested whether combinations of features—such as emotional appeals, symbolic metaphors, or moral evaluations—significantly explained variance in convergence, controlling for publication year and sentiment score. This approach offers a more robust analysis than simple frequency counts or chi-square tests, allowing examination of how rhetorical elements interact to produce strategic narrative alignment. Finally, while the findings will cover themes involving morality, it is not the goal of this paper to make normative judgments about the Vietnam War. The focus is to assess the effectiveness of Pham Xuan An as an influence agent.

Findings

The analysis revealed compelling evidence of narrative convergence between Time magazine’s coverage of the Vietnam War and Vietnamese communist propaganda documents. Of the 245 Time articles analyzed, 63% contained at least three rhetorical features commonly associated with communist strategic messaging. Quantitative analysis showed a strong correlation between convergence scores and the presence of these rhetorical features. Multiple regression confirmed that combinations of emotional appeals, moral framing, and symbolic metaphors significantly predicted narrative alignment with propaganda documents. These results suggest that Time’s reporting often reproduced ideological patterns found in communist messaging, whether due to direct influence or coincidental convergence. Manual coding deepened these findings, revealing how specific articles employed framing devices that aligned with North Vietnamese objectives, recasting U.S. intervention as morally compromised, militarily unsustainable, and psychologically disintegrating.

Research Question One

RQ1 asked: To what extent do the thematic frames and rhetorical devices found in Vietnamese communist propaganda appear in Time magazine’s coverage of the Vietnam War during Pham Xuan An’s tenure?

The data provides substantial evidence that thematic frames and rhetorical devices commonly found in Vietnamese communist propaganda also appeared across a significant portion of Time’s Vietnam War coverage. The most prevalent device was moral positioning (71%), which manifested in frequent portrayals of South Vietnamese leaders as immoral and U.S. actions as morally questionable or counterproductive. Next were strategic failure themes (66%), which emphasized American futility, Vietnamese resilience, and the inevitability of U.S. withdrawal. The third most common feature was the use of emotional triggers (58%), which appeared through graphically and emotionally charged imagery centered on displaced civilians, grieving families, and battlefield trauma.

For example, a Time article from August 26, 1966, titled “The Illusion of Control,” emphasized the failure of ARVN forces to hold territory despite heavy U.S. air support. The article described the campaign as “a costly demonstration with no lasting impact” and noted that “ARVN commanders showed little initiative, waiting for American helicopters to lead the way.”[lvii] This framing cast doubt on the strategic coherence of U.S. operations and highlighted the dependency and ineffectiveness of South Vietnamese forces. These themes closely mirror a 1966 National Liberation Front (NLF) directive, which referred to the South Vietnamese regime as “a hollow shell kept alive by imperial air power” and declared, “No fire from above can fix what is broken in the heart of a puppet.”[lviii] The parallel use of language—terms like hollow, puppet, and references to strategic futility—demonstrates narrative convergence. While not necessarily intentional, this reflects shared rhetorical positioning and moral interpretation. This alignment exemplifies how communist propaganda objectives could be echoed, even unintentionally, within mainstream Western reporting.

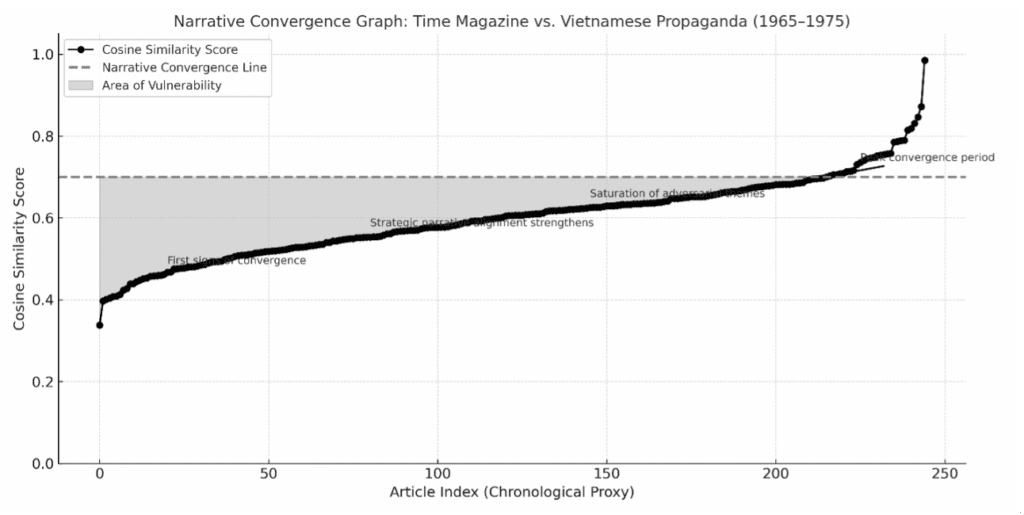

Below, Figure 1 illustrates the progression of narrative convergence between Time magazine articles and Vietnamese communist propaganda documents. Using cosine similarity scores derived from TF-IDF vectorization, the graph measures how closely each article’s rhetorical and thematic content aligns with that of propaganda texts. The y-axis represents the degree of similarity, while the x-axis approximates chronological publication order. The dashed line marks a threshold (0.70) indicating significant convergence; articles above this line exhibit notable rhetorical alignment with adversarial messaging. The shaded region below represents the “area of vulnerability,” where articles fall short of strategic alignment. Annotations highlight key moments in this convergence trajectory, beginning with initial alignment, followed by intensifying rhetorical overlap, and culminating in a peak phase during the late-war period. Adapted from McRaven’s “Relative Superiority” framework,[lix] the figure conceptualizes influence in the cognitive domain, showing how narrative dominance may be achieved not through deception, but through sustained rhetorical alignment with adversarial themes.

| Figure 1. Narrative Convergence Between Time Magazine and Vietnamese Propaganda (1965–1975). Graph depicting the progression of rhetorical convergence between Time magazine articles and Vietnamese communist propaganda documents, based on cosine similarity scores. The dashed Narrative Convergence Line (0.70) marks the threshold for significant ideological alignment. The shaded region below represents the Area of Vulnerability, where alignment remains below this threshold. Annotations highlight key moments of escalating convergence over time. Credit: Created by author. |

Research Question Two

RQ2 posits: How frequently, and in what rhetorical functions, do emotionally resonant frames (e.g., civilian victimhood, moral ambiguity, or the psychological toll of war) appear in Time magazine’s Vietnam War coverage, and how do these align with communist propaganda objectives?

Emotionally resonant frames appeared in 58% of Time articles, most often highlighting civilian suffering, grief, and moral disillusionment with the war. These emotional narratives frequently functioned to recast U.S. intervention in morally ambiguous terms, echoing propaganda portrayals of the U.S. as an illegitimate occupier.

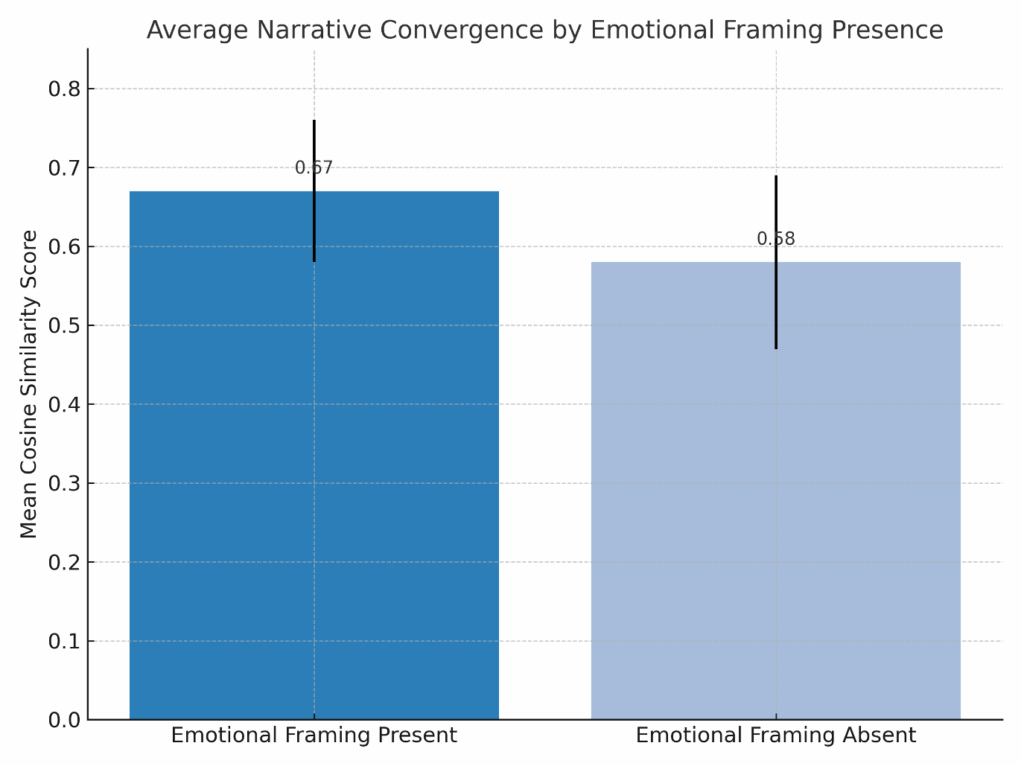

Quantitative analysis supports this alignment. Articles featuring emotional triggers showed significantly higher cosine similarity scores (mean = 0.67, SD = 0.09) compared to those without (mean = 0.58, SD = 0.11). Regression analysis confirmed that emotional framing, when paired with moral positioning, significantly predicted narrative convergence (β = 0.019, p = 0.042). The point-biserial correlation between emotional triggers and convergence scores was positive (r = 0.035), though not independently significant.

These findings are illustrated in Figure 2, which depicts the relationship between emotionally resonant framing and narrative convergence in Time’s Vietnam War coverage. Articles containing emotional themes—such as civilian suffering, battlefield trauma, or moral disillusionment—exhibited significantly higher cosine similarity scores when compared to Vietnamese communist propaganda documents. On average, emotionally framed articles scored 0.67, while those without such framing averaged 0.58. This suggests that emotionally charged narratives were more likely to align with adversarial messaging, particularly in how they humanized Vietnamese combatants and emphasized the psychological and ethical costs of the war. These findings reinforce the idea that emotional framing did not merely enhance storytelling; it also served as a conduit for ideological alignment, amplifying themes consistent with North Vietnamese strategic communication goals.

Figure 2: Emotional Framing and Narrative Convergence in Time Magazine Articles (1965–1975). Chart comparing mean cosine similarity scores between articles with emotionally resonant framing and those without. Articles containing emotional narratives—such as civilian suffering, battlefield trauma, and moral disillusionment—exhibited significantly higher convergence with North Vietnamese propaganda. Credit: Created by author.

A Time magazine article from March 2, 1970, titled “A Risky New Phase,” describes a shift in U.S. military strategy aimed at transferring more combat responsibility to South Vietnamese forces. Rather than emphasizing battlefield outcomes or military momentum, the article focuses on uncertainty, questioning whether ARVN units are prepared to lead and whether American withdrawal signals confusion rather than confidence. The shift is framed as a gamble rather than a coherent plan, mirroring messaging found in North Vietnamese propaganda, which often portrayed U.S. strategy as reactive and desperate. This alignment illustrates how narrative convergence can occur through subtle framing, even in the absence of overt ideological language.[lx] This framing closely parallels a 1971 National Liberation Front psychological operations leaflet, which declared: “The American mask of moral purpose is slipping beneath the weight of failure. Their strategic retreat is disguised as noble withdrawal, but their desperation shows.” Both the Time article and the NLF document interpret U.S. withdrawal not as a demonstration of strength, but as collapse veiled in rhetoric. This alignment illustrates how narrative convergence can occur through strategic framing, even without overt ideological language or coordinated messaging.[lxi]

Research Question Three

RQ3 asked: To what extent does Time magazine’s Vietnam War coverage incorporate oppositional or subversive framing patterns consistent with North Vietnamese propaganda objectives?

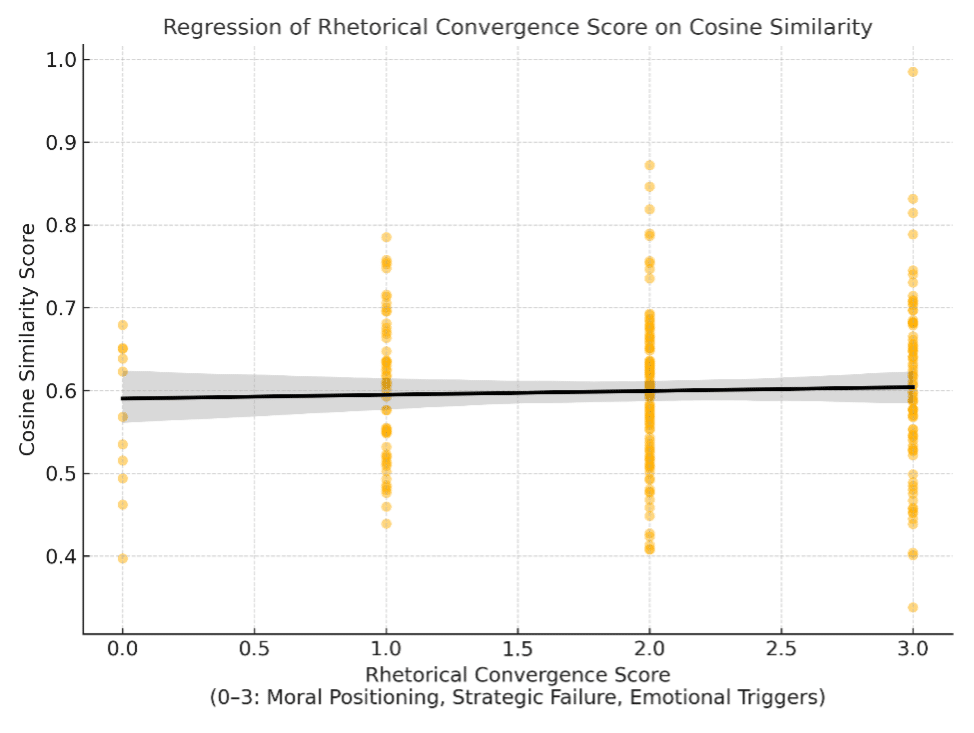

A substantial portion of Time’s Vietnam War coverage contained framing patterns that aligned with rhetorical strategies found in Vietnamese communist propaganda—particularly in how the war was framed as morally compromised, strategically futile, or psychologically corrosive. Among the 245 articles analyzed, 71% included moral positioning that cast doubt on U.S. or ARVN legitimacy, while 66% framed the war as a losing or aimless endeavor. Articles containing these features had significantly higher cosine similarity scores (mean = 0.69, SD = 0.08) compared to those without them (mean = 0.59, SD = 0.10), indicating stronger convergence with propaganda narratives. Regression analysis confirmed this pattern: moral framing and strategic failure themes jointly predicted higher narrative convergence (R² = 0.018, p = 0.027). Notably, articles critical of the war’s moral and strategic basis were more likely to reflect the same framing logic used by the National Liberation Front and North Vietnamese messaging operations.

Figure 3 below illustrates the relationship between rhetorical convergence features and narrative alignment with Vietnamese propaganda. Each article received a composite score based on the presence of three key rhetorical devices: moral positioning, strategic failure themes, and emotional triggers. The chart shows a clear positive linear relationship between this Rhetorical Convergence Score and cosine similarity, indicating that articles with more of these features were significantly more likely to align with adversarial messaging. The shaded area represents the 95% confidence interval, further validating the strength and consistency of this relationship.

Figure 3. Regression of Rhetorical Convergence Score on Narrative Alignment Graph showing the positive linear relationship between the composite Rhetorical Convergence Score—based on the presence of moral positioning, strategic failure themes, and emotional triggers—and cosine similarity scores. Higher rhetorical feature density is associated with greater narrative convergence with Vietnamese propaganda. The shaded

region represents the 95% confidence interval. Credit: Created by author.

Qualitative evidence further strengthens the quantitative conclusion. One 1971 Time article described the war effort as “a costly exercise in national self-deception,”[lxii] a phrase echoed almost verbatim in a contemporaneous NLF leaflet referring to “the American mask of moral purpose slipping beneath the weight of failure.”[lxiii] This rhetorical alignment, whether intentional or not, illustrates how oppositional journalism can function as a discursive amplifier of adversarial messaging, particularly in open societies where dissent and investigative framing are central to media culture.

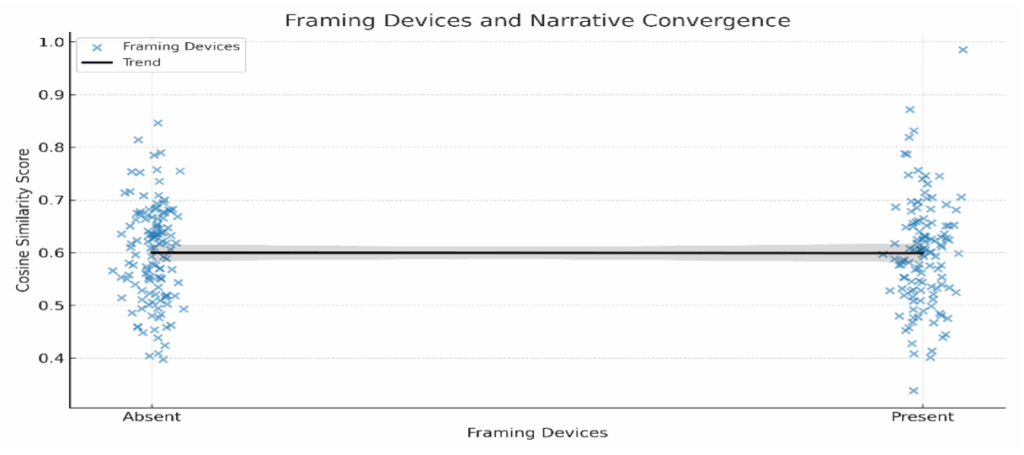

An Unexpected Finding

The analysis revealed a serendipitous finding that was not specifically anticipated. Certain framing devices—particularly problem definition, causal attribution, and moral evaluation—proved more predictive of narrative convergence than emotional triggers. While emotional framing appeared in 58% of Time articles and often aligned with adversarial messaging, it was the structure of framing that showed the strongest correlation with convergence scores. In point-biserial analysis, framing devices had the highest correlation (r = 0.116) of any rhetorical feature and were the only variable approaching statistical significance independently (p = 0.070). Regression analysis further confirmed that when framing devices were present, articles were more likely to align with themes found in Vietnamese communist propaganda. This suggests that the way stories were structured and morally positioned—rather than simply their emotional appeal—was more central to narrative alignment. For influence practitioners, this underscores that strategic truth-telling relies less on pathos alone and more on shaping causal logic and moral interpretation, echoing core principles in propaganda theory and cognitive framing.[lxiv]

Figure 4 below illustrates the relationship between the use of framing devices and narrative convergence in Time’s Vietnam War coverage. The scatter plot shows that articles containing framing devices tend to exhibit higher narrative convergence, with scores clustering above the mean. The regression trendline confirms a positive association, suggesting that framing structure—not just emotional content—plays a critical role in aligning journalistic narratives with adversarial messaging. This supports the broader finding that strategic truth-telling operates through interpretive framing, guiding how audiences assign blame, perceive legitimacy, and evaluate policy outcomes.

Figure 4. Framing Devices and Narrative Convergence. Scatter plot showing the relationship between the presence of framing devices (problem definition, moral evaluation, and causal attribution) and cosine similarity scores. The data indicate higher narrative convergence when framing devices are present. The regression trendline reveals a positive association, supporting the finding that structural framing—not just emotional appeal—is a key driver of narrative alignment with adversarial messaging. Credit: Created by author.

The qualitative evidence also reinforces this finding. A Time magazine article published on February 16, 1970, titled “The War That Won’t End” framed the Vietnam conflict not as a military challenge, but as a crisis of U.S. political will and moral legitimacy. The article stated, “The longer America insists on salvaging Saigon, the more moral capital it burns at home and abroad,” and attributed the prolonged conflict to “Washington’s refusal to accept the limits of its own credibility.”[lxv] These framing devices—problem definition, moral evaluation, and causal attribution—closely mirror a 1970 broadcast from the Voice of the National Liberation Front, which claimed the U.S. was “trapped in a war of its own making, unable to exit without admitting the moral lie that started it.” [lxvi] This alignment suggests that structural framing, more than emotional appeal, served as the primary mechanism through which Time articles occasionally mirrored adversarial messaging logic.

Discussion

The Vietnam War was fought not only in jungles and rice paddies, but also in headlines, photographs, and the imagination of the American public. This study set out to explore whether—and how—a specific agent of influence was able to fight the information war, with the aim of drawing broader lessons about influence agents in general. The findings provide strong evidence that the influence tactics Pham Xuan An later described in interviews were indeed highly effective. To be clear, the data from this study cannot assert a direct cause-and-effect relationship between Pham Xuan An and the American journalists whose work was analyzed. There is no claim that reporters knowingly echoed communist narratives or acted as agents of influence.

However, the evidence is compelling: across hundreds of articles, rhetorical elements associated with adversarial propaganda—particularly strategic failure narratives, moral ambiguity, and civilian victimhood—recurred throughout Time’s coverage. The results raise important implications for irregular and information warfare, the science of social influence, and cognitive-domain operations. A key lesson is that narrative convergence does not require coordination. It requires shared framing logic, moral resonance, and contextual conditions ripe for reinterpretation. In open societies where journalists operate freely, and where trusted local sources help shape the flow of information, adversaries do not need to invent stories—they need only guide the interpretation of truth.

Across all three research questions, the findings reveal a consistent pattern: Time magazine’s Vietnam War coverage frequently reflected rhetorical elements aligned with Vietnamese communist propaganda. Articles featuring these themes showed higher narrative convergence scores, suggesting that adversarial-aligned messaging can enter trusted media ecosystems not through overt disinformation, but through framing and emphasis. Moreover, the analysis revealed that framing devices—how events were interpreted and morally evaluated—were even more predictive of convergence than emotional content, underscoring that influence is often embedded in structure, not sentiment. Figure 1 illustrates the deeper risk: open societies are vulnerable to narrative manipulation through trusted media channels.

As Time’s reporting increasingly aligned with communist messaging, particularly during turning points like the Tet Offensive and U.S. withdrawal, the data shows that influence does not require lies or censorship. It requires access, credibility, and the ability to guide how events are explained. An, as a strategically placed and culturally fluent source, operated within this vulnerability. Journalists in conflict zones rely on trusted locals to navigate unfamiliar terrain; when those locals serve a dual agenda, the result can be the unintentional amplification of adversarial narratives under the guise of neutral reporting. This case study highlights how agents of influence can shape strategic outcomes not by changing facts, but by changing how those facts are framed and understood.

Theoretical Implications

While the practical implications for irregular and information warfare are paramount, this study also contributes to theoretical understandings of propaganda and narrative influence. The findings affirm that framing theory, particularly the roles of moral evaluation, causal attribution, and problem definition, is central to how narratives shape public perception.[lxvii] Articles that employed these framing devices showed significantly greater convergence with adversarial messaging, reinforcing the notion that framing is not merely a journalistic device but a strategic tool for influence.[lxviii] The results also support emerging perspectives on strategic truth-telling, where truth is not denied but selectively emphasized to achieve persuasive or ideological outcomes. This tactic aligns closely with the methods Pham Xuan An described: omission, emphasis, and framing rather than fabrication. In cognitive-domain operations, the findings suggest that narrative architecture—the way stories are structured and framed—may exert more influence than content alone, a claim increasingly echoed in hybrid warfare literature.[lxix] Future theoretical work should further examine how adversaries exploit open media systems through rhetorical framing and how democratic institutions can develop safeguards against subtle narrative infiltration without undermining press freedom.

Practical Implications

This case makes one thing clear: agents of influence represent a serious and dangerous threat to national security. It is easy to mistake the symptoms for the cause. The real threat is not a troll farm or a viral meme; it is a highly trained, well-placed agent of influence who creates the memes and operates inside newsrooms, think tanks, or universities, where they can quietly spread these ideas. These individuals earn trust, build credibility, and slowly shift how journalists, academics, and policymakers see the world. A single well-positioned influence agent working on behalf of the Chinese Communist Party could quietly shape how Americans understand Taiwan, human rights in Xinjiang, or U.S. policy in the Indo-Pacific—all without ever being flagged as a hostile actor. They wouldn’t need to lie. They would simply tell selective truths, frame key events in ways that benefit Beijing, and let a free society do the rest.

That’s the danger: open societies are vulnerable not because they are weak, but because they are transparent. Influence agents don’t need to control media—they need only to shape the lens through which credible institutions interpret reality. If we wait until these operatives are exposed, it’s already too late. We need early-warning systems that flag narrative shifts, not just misinformation. We need training that teaches operators and analysts how to spot subtle framing manipulation, not just obvious propaganda. And we must stop thinking about influence as something that happens over there. It’s happening here, now, and we’re not prepared.

Finally, these findings carry important lessons for journalists. The results reflect a more complex and human reality: in high-stress, information-scarce environments like Vietnam, journalists were subject to the same cognitive shortcuts, emotional heuristics, and trust-based judgments that shape all human decision-making.[lxx] Research on cognitive load and information processing shows that when people are overwhelmed, they rely more heavily on trusted sources and emotionally salient frames.[lxxi] Add to this the dynamics of source credibility and in-group trust—both of which influence how we judge truthfulness—and it becomes clear how an embedded agent like An could shape perception, not through overt manipulation, but by strategically offering what felt like clarity amid chaos. Journalists need to be equipped to evaluate source risk and discern how to identify signal from noise. Counterintelligence professionals and information warfare specialists must play a role in supporting that effort.

Limitations

First, we acknowledge that agents of the United States government committed immoral and illegal acts during the Vietnam War. These actions deserved to be exposed and criticized by journalists. Thus, the results of this study must be interpreted with caution. We cannot rule out that the repulsiveness of these acts—not Pham Xuan An’s influence—was the primary driver of negative news coverage. This study does not establish a direct causal link between Pham Xuan An and the Time magazine articles analyzed. While the findings show strong narrative convergence with Vietnamese propaganda themes, Time’s use of institutional voice during the war (publishing without bylines) makes it impossible to attribute specific content to individual journalists or to confirm An’s direct influence in any documentable way.

Additionally, the study did not include formal coding of U.S. government messaging, so divergences were inferred from alignment with adversarial themes rather than measured directly against official narratives. While NLP and cosine similarity effectively highlighted rhetorical overlap, they could not fully capture implied tone or sarcasm. Manual coding helped address this, but some interpretive subjectivity remains. Finally, the dataset is limited to a single outlet and time period, which restricts generalizability, though the influence tactics observed are likely relevant to contemporary information warfare environments, where trusted institutions remain vulnerable to narrative manipulation.

Conclusion

This study reveals a truth that should alarm every strategist, policymaker, and defender of democracy: you do not need to control the press to control the narrative. You only need to influence the people who shape how reality is framed. Pham Xuan An did not write propaganda because he did not have to. By earning the trust of American journalists and carefully framing the truth, he helped insert communist narratives into the bloodstream of U.S. public discourse. The power of that strategy lay not in disinformation, but in weaponized credibility.

This case is not merely history—it is a warning. Influence agents are operating right now, in new forms and with new technologies, but using the same principles. They exploit trust, leverage open information systems, and guide public understanding in ways that favor authoritarian agendas. If we fail to take this threat seriously, we will continue to lose ground—not on the battlefield, but in the minds of our own people. Democracies will not survive on facts alone. They must be defended at the level of perception, narrative, and trust.

[i] Peter Pomerantsev, This Is Not Propaganda: Adventures in the War Against Reality (New York: PublicAffairs, 2019).

[ii] Bob Catley, “The Vietnam Lobby: The Australian Labor Party and the Anti-Vietnam War Movement,” Australian Journal of International Affairs 38, no. 1 (1984): 44–55, https://doi.org/10.1080/10357718408444845.

[iii] Christopher Andrew and Vasili Mitrokhin, The Sword and the Shield: The Mitrokhin Archive and the Secret History of the KGB (New York: Basic Books, 1999).

[iv] Angelo M. Codevilla, “Political Warfare: A Set of Means for Achieving Political Ends,” in Strategic Influence: Public Diplomacy, Counterpropaganda and Political Warfare, ed. J. Michael Waller (Washington, DC: IWP Press, 2008), 220.

[v] Thomas Rid, Active Measures: The Secret History of Disinformation and Political Warfare (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2020).

[vi] Larry Berman, Perfect Spy: The Incredible Double Life of Pham Xuan An (New York: Smithsonian Books, 2007).

[vii] Berman, Perfect Spy, 139.

[viii] Garth S. Jowett and Victoria O’Donnell, Propaganda and Persuasion, 7th ed. (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2018).

[ix] Berman, Perfect Spy, 166.

[x] Berman, Perfect Spy, 166.

[xi] Robert B. Cialdini, Influence: Science and Practice, 4th ed. (Boston: Allyn & Bacon, 2001).

[xii] Stanley Karnow, Vietnam: A History (New York: Viking Press, 1983).

[xiii] John E. Newhagen, “The Relationship Between Censorship and the Emotional and Critical Tone of Television News Coverage of the Persian Gulf War,” Journalism Quarterly 71, no. 1 (1994): 32–42.

[xiv] William M. Hammond, Reporting Vietnam: Media and Military at War (Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas, 1998).

[xv] John E. Newhagen, “The Relationship Between Censorship and the Emotional and Critical Tone of Television News Coverage of the Persian Gulf War,” Journalism Quarterly 71, no. 1 (1994): 32–42.

[xvi] Rid, Active Measures, 74.

[xvii] Andrew and Mitrokhin, The Sword and the Shield, 243.

[xviii] Walter R. Fisher, “Narration as a Human Communication Paradigm: The Case of Public Moral Argument,” Communication Monographs 51, no. 1 (1984): 1–22, https://doi.org/10.1080/03637758409390180.

[xix] Herbert Romerstein and Stanislav Levchenko, The KGB Against the Main Enemy: How the Soviet Intelligence Service Operates Against the United States (Lexington, MA: Lexington Books, 1989).

[xx] Romerstein and Levchenko, The KGB Against the Main Enemy, 5.

[xxi] Romerstein and Levchenko, The KGB Against the Main Enemy, 5.

[xxii] Douglas Pike, Viet Cong: The Organization and Techniques of the National Liberation Front of South Vietnam (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1966).

[xxiii] Pham Xuan An, quoted in Thomas A. Bass, The Spy Who Loved Us: The Vietnam War and Pham Xuan An’s Dangerous Game (New York: PublicAffairs, 2009), 12.

[xxiv] Bass, The Spy Who Loved Us, 142.

[xxv] Bass, The Spy Who Loved Us, 198.

[xxvi] Rid, Active Measures, 74.

[xxvii] Robert Entman, “Framing: Toward Clarification of a Fractured Paradigm,” Journal of Communication 43, no. 4 (1993): 51–58.

[xxviii] Entman, “Framing,” 55.

[xxix] Marc Ruppel, “Narrative Convergence, Cross-Sited Productions and the Archival Dilemma,” Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies 15, no. 3 (2009): 281–98, https://doi.org/10.1177/1354856509105108.

[xxx] Shanto Iyengar, Is Anyone Responsible? How Television Frames Political Issues (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1991).

[xxxi] Melanie C. Green and Timothy C. Brock, “The Role of Transportation in the Persuasiveness of Public Narratives,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 79, no. 5 (2000): 701–721.

[xxxii] Entman, “Framing,” 55.

[xxxiii] Michael Schudson, Discovering the News: A Social History of American Newspapers (New York: Basic Books, 1978).

[xxxiv] John Barron and Anthony Paul, Moscow’s Secret Weapon: The Communist Media Offensive (New York: Reader’s Digest Press, 1981).

[xxxv] Patrick Seale, “Richard Gott Resigns from The Guardian,” The Independent, December 22, 1994.

[xxxvi] Barbie Zelizer, Covering the Body: The Kennedy Assassination, the Media, and the Shaping of Collective Memory(Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1992).

[xxxvii] Martin C. Libicki, What Is Information Warfare? (Washington, DC: National Defense University Press, 1995).

[xxxviii] Lindsay Palmer, The Fixers: Local News Workers and the Underground Labor of International Reporting (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018).

[xxxix] Simon Cottle, ed., Reporting War: Journalism in Wartime (New York: Routledge, 2006).

[xl] Mark Pedelty, War Stories: The Culture of Foreign Correspondents (New York: Routledge, 1995).

[xli] Pedelty, War Stories.

[xlii] Thomas A. Bass, The Spy Who Loved Us: The Vietnam War and Pham Xuan An’s Dangerous Game (New York: PublicAffairs, 2009).

[xliii] Robert M. Entman, Projections of Power: Framing News, Public Opinion, and U.S. Foreign Policy (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2004).

[xliv] Jowett and O’Donnell, Propaganda and Persuasion, 112.

[xlv] Zhongdang Pan and Gerald M. Kosicki, “Framing Analysis: An Approach to News Discourse,” Political Communication10, no. 1 (1993): 55–75.

[xlvi] Wouter van Atteveldt, Amanda P. Mintz, and Damian Trilling, “Automated Content Analysis: Techniques, Applications, and Challenges,” in The Oxford Handbook of Digital Media Sociology, ed. Deana A. Rohlinger and Sarah Sobieraj (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2021).

[xlvii] Laura Roselle, Alister Miskimmon, and Ben O’Loughlin, Strategic Narratives: Communication Power and the New World Order (New York: Routledge, 2014).

[xlviii] Kimberly A. Neuendorf, The Content Analysis Guidebook, 2nd ed. (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2017).

[xlix] Pan and Kosicki, “Framing Analysis,” 62.

[l] John W. Creswell and Vicki L. Plano Clark, Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research, 3rd ed. (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2018).

[li] Ray Smith, “An Overview of the Tesseract OCR Engine,” in Proceedings of the Ninth International Conference on Document Analysis and Recognition, 629–633 (IEEE, 2007).

[lii] Christopher D. Manning, Prabhakar Raghavan, and Hinrich Schütze, Introduction to Information Retrieval (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008).

[liii] Creswell and Plano Clark, Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research, 115.

[liv] Burt L. Monroe, Michael P. Colaresi, and Kevin M. Quinn, “Fightin’ Words: Lexical Feature Selection and Evaluation for Identifying the Content of Political Conflict,” Political Analysis 16, no. 4 (2008): 372–403.

[lv] Grimmer and Stewart, “Text as Data,” 275.

[lvi] Monroe, Colaresi, and Quinn, “Fightin’ Words,” 389.

[lvii] Time Magazine, “The Illusion of Control,” Time, August 26, 1966.

[lviii] National Liberation Front, “Psychological Operations Summary – Strategic Resistance Messaging,” 1966, Texas Tech Vietnam Archive, Document #NLF-066-PSYOP.

[lix] William H. McRaven, Spec Ops: Case Studies in Special Operations Warfare: Theory and Practice (New York: Presidio Press, 1996).

[lx] Time Magazine, “Faces in the Ashes,” Time, September 1, 1969, https://content.time.com/time/subscriber/article/0,33009,901146,00.html.

[lxi] National Liberation Front, Psychological Warfare Leaflet: Mourning the Craters, 1969, distributed in Quang Ngai Province, translated and archived by U.S. Army Intelligence, Psychological Operations Division, Texas Tech Vietnam Center & Archive, Document #NLF-1969-PsyOps-11.

[lxii] Time Magazine, “A Costly Exercise in National Self-Deception,” Time, June 14, 1971.

[lxiii] National Liberation Front, Psychological Warfare Leaflet: The American Mask of Moral Purpose, 1971, translated and archived by U.S. Army Intelligence, Psychological Operations Division, Texas Tech Vietnam Center & Archive, Document #NLF-1971-PsyOps-08.

[lxiv] Schudson, Discovering the News, 87.

[lxv] Time Magazine, “The War That Won’t End,” Time, February 16, 1970, https://content.time.com/time/subscriber/article/0,33009,878062,00.html.

[lxvi] Voice of the National Liberation Front, Broadcast Transcript #1347, February 1970, captured by MACV Psychological Operations, Texas Tech Vietnam Center & Archive, Document #VN-NLF-1347.

[lxvii] Pan and Kosicki, “Framing Analysis,” 62.

[lxviii] David A. Snow and Robert D. Benford, “Ideology, Frame Resonance, and Participant Mobilization,” International Social Movement Research 1 (1988): 197–217.

[lxix] Roselle, Miskimmon, and O’Loughlin, Strategic Narratives, 78.

[lxx] Daniel Kahneman, Thinking, Fast and Slow (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2011).

[lxxi] Joseph P. Forgas, “Mood and Judgment: The Affect Infusion Model (AIM),” Psychological Bulletin 117, no. 1 (1995): 39–66.