Robert S. Burrell, University of South Florida, Tampa, Florida, USA

Arman Mahmoudian, University of South Florida, Tampa, Florida, USA

INTRODUCTION

Since Vladimir Putin assumed power in 1999, Russia has witnessed significant civil unrest, demonstrating widespread dissatisfaction with the government and its policies. Putin’s harsh crackdowns have failed to quell the Russian population’s desire for increased transparency, government accountability, and economic equality. In this context, it is crucial to assess the potential for further civil unrest in Russia. This paper utilizes a data-centric methodology to examine Vladimir Putin’s governance and the opposition to it in terms of resilience and resistance. It leverages analytical data from top universities, financial institutions, governmental agencies, and non-governmental organizations to inform a four-phase process.

CONTACT Robert S. Burrell | robertburrell@usf.edu

The views expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views, policy, or position of the U.S. Government, the University of South Florida, or the Department of Defense. © 2024 Arizona State University

PHASE ONE: MEASURING RUSSIA’S RESILIENCE AND RESISTANCE

Phase one measures the Putin regime’s resiliency, as well as Russia’s resistance potential, and then assesses the likely success of external support for resilience or resistance. Phase two identifies prevalent resistance organizations within Russia, categorizes these organizations along a continuum, and classifies their general nature. Phase three assesses one resistance organization (Communist Party of the Russian Federation) by examining its leadership, motivation, operating environment, organization, and activities. Phase four rationally evaluates the gathered information to make recommendations concerning potential external support for Russia’s intrastate conflict.

Phase 1: Measuring Russia’s Resilience and Resistance

Phase one frames Russia in terms of resilience and resistance (resiliency refers to the Putin regime’s ability to overcome internal or external subversion, coercion, or aggression, while resistance refers to Russian society’s, the population’s, or a subgroup’s opposition to malign indigenous power structures). Russia’s resiliency and resistance metrics remain essential within the context of the current war in Ukraine, as well as Russia’s broader confrontation with Western nations, in addition to possible external support by allies or partners like India, Iran, or China. The study of resilience and resistance in Russia reveals potential for (a) possible uses of external support to increase the Putin regime’s resiliency, and (b) possibilities to subvert and destabilize Putin’s regime.

Measuring Russia’s Resilience

Russia is the largest nation on earth in terms of geography and nearly two times the size of the United States. Russia’s population is 140 million, slightly more than Mexico’s. The largest ethnic group is Russian at 78%, followed by smaller and varied ethnicities, the largest of which are the Tatars at 3.7%. The Russian diaspora includes 30 million living abroad, of whom 9 million live in Ukraine. In terms of language, the country is more unified with 86% speaking Russian as their primary tongue. The Central Intelligence Agency claims 15-20% of Russians practice the Orthodox faith and 10-15% are Muslim, with the majority nonpracticing believers or nonbelievers. In terms of governance, Russia officially abides by a semi-presidential administration but ostensibly acts as a dictatorship under President Vladimir Putin.[1]

Historical Factors

Alongside geography and demography, history plays an equally crucial role in Russian resilience. Unlike most European nations, which have deep cultural and civilizational ties with similar nations—for example, the Anglo-Saxon connections between the British, Canadians, Americans, and Australians, or the Germanic links among Germany, Switzerland, Austria, and the Netherlands—Russian kinship consists of Slavic or Russian-speaking peoples. Thus, Russia lacks a broader sense of historical ties with Western nations. This dynamic results in Russia as being not alone but a lonely civilization. This perceived isolation influences Russia’s resilience. The sense of uniqueness or separation prevents Russians from being inspired by Western forms of governance.

Russia’s national identity, shaped by its historical context, plays a vital role in its resilience. Since the formation of the Russian state following the Mongol invasion in the thirteenth century, Russia’s identity has been significantly influenced by its conflicts with Western civilization. Historically, Russia has viewed European powers such as Poland, Sweden, France, the United Kingdom, and Germany as adversaries. Western civilization, including its espousal of democracy, capitalism, and liberalism, is perceived by many Russians as a menace. This historical enmity undermines resistance against authoritarianism in Russia.

Russia’s historical narrative emphasizes resilience and survival in the face of external threats. This narrative fosters a sense of unity and a collective identity centered around the idea of a besieged fortress, reinforcing the nation’s resolve to withstand external pressures. Throughout history, Russian governments have tried to solidify their grip on power by portraying Western influence as a destabilizing force, as many Russians equate stability with the preservation of their unique identity and sovereignty.

Political Factors

Russia’s political spectrum is profoundly shaped by a combination of geography, demography, history, and identity. Putin’s emphasis on traditional values and national pride serves as a counterbalance to Western liberal ideals. By promoting a distinct Russian identity rooted in historical experiences and cultural heritage, the state strengthens its position and minimizes the appeal of foreign ideologies. This deliberate cultivation of a unique Russian identity not only bolsters internal cohesion but also legitimizes Putin’s authority and makes it harder for external influences to inspire change.

The nation’s perceived isolation, historical antagonism towards the West, and emphasis on a unique national identity contribute to its resilience against external influences and internal resistance to authoritarianism. Understanding these factors is essential for comprehending the complexities of Russia’s political landscape and its enduring sense of uniqueness in the global arena. Additionally, it also remains important to consider the historical memory of civic movements in Russia. Russians have not had favorable experiences with attempts to democratize the country, which has left a significant imprint on their collective consciousness. There have been two major efforts in Russian history to establish a democratic system, both of which ended in disappointment and turmoil (the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917 and the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991).

The other political factor contributing to the Russian regime’s resilience is Putin’s carefully cultivated persona of strength in the face of adversity. Since his entrance on the political scene, Putin has consistently portrayed himself as a strongman by (a) decisively putting oligarchs in their place, (b) forcefully quelling the Chechen insurgency, and (c) standing firm against international sanctions. By curbing the power of the oligarchs, he reasserted state control over key economic sectors, signaling that no individual or entity could challenge his authority. His brutal military campaign in Chechnya demonstrated his willingness to use overwhelming force to maintain territorial integrity and suppress separatism. Additionally, Putin’s defiant stance against Western sanctions, imposed in response to actions such as the annexation of Crimea and interference in Ukraine, has further solidified his image as a resilient leader who can navigate and withstand external pressures. This combination of domestic control and international defiance has bolstered the Russian government’s stability and resilience, reinforcing the perception of Putin as an indispensable and invincible leader.

Vladimir Putin’s political persona, characterized by his strongman image and Napoleonic charisma, has significantly contributed to the resilience of the Russian government.[2] This cultivated image of invincibility and decisive leadership has allowed Putin to centralize power and maintain tight control over the Russian state. His approach, marked by the suppression of dissent, extensive propaganda, and an appeal to nationalism, fosters a collective identity that prioritizes state survival over individual freedoms. This consolidation of power, akin to historical fascist regimes, has enabled the Russian government to navigate internal crises and external pressures with a semblance of unity and stability. Despite economic sanctions and international condemnation, Putin’s ability to project strength and resolve has fortified the regime’s endurance, effectively manipulating public perception and stifling opposition.

Economic Factors

The ability to generate significant revenue is a crucial component of Putin’s power, as it enables his regime to finance its operations and maintain public services, even in times of crisis. In 2022, the World Bank estimated Russian gross domestic product as the eighth largest in the world at $2.2 trillion, comparable to Canada’s.[3] Having a relatively large GDP and robust revenue generation capability provide a foundation for the government’s power and stability, enabling it to withstand various internal and external pressures. It also allows Putin to maintain a high level of government spending on military, security, and social programs, which in turn bolsters his regime’s resilience. The Federation’s primary export remains mining and extractive industries (coal, oil, gas), but supplemented by a large defense industry and other types of industrial applications with sales worldwide.[4] Russia’s reliance on fossil fuel exports strengthens Putin’s resiliency by providing a steady stream of income for governance functions that are relatively independent of direct taxation on its citizens. This fiscal buffer helps the government maintain social stability and mitigate the potential for civil unrest.

Despite the historical, political, and economic factors supporting the Putin regime, the analytics demonstrate that the Russian Federation has both low and below-average indicators of resiliency. The following percentiles rank Russia relative to other countries worldwide with 0% as the lowest and 100% as the highest. According to the World Bank, and in comparison, with other nations, Russia ranks at 14.49% in government accountability; 16.04% in political stability; 25.94% in government effectiveness; 13.21% in regulation efficiency; 12.26% in rule of law; and 19.34% in control of corruption.[5] The Fund for Peace’s state fragility index, ranks Russian fragility as above average in comparison with others at 53 of 179 (or 29.31%), between that of Turkey and Cambodia.[6] Additionally, the Swiss Re Institute’s macroeconomic resilience index showcases Russia’s resiliency as low (22 of 31 developed countries analyzed) at 29.03% In order to measure Russia’s national will in support of Putin’s regime, we have chosen to rely on a framework developed by Delbert C. Miller.[7]

The following table utilizes Miller’s analysis methods (as closely as possible in line with available polling) and five categories to determine national morale of the Russian Federation. (1) We consider Russians as the ingroup, in which, when polled, 65% were proud of their nationality.[8] (2) In the same study, about 36% were optimistic or excited about the prospects of Russia’s political system over the next 10 years.[9] (3) In the third category concerning the competency of national leaders, Vladimir Putin’s approval rating is soaring at 85%.[10] (4) In terms of Russian confidence in current resources to defend the interests of the state, about 77% of those polled support the war in Ukraine.[11] Lastly, (5) 52% of those polled believe “Russians are a great people of particular significance to the world,” which likely aligns with the Putin regime’s national goal.[12] All five factors are outlined in Table 2 to assess national morale, which we assess collectively as 63%.

| FIVE FACTORS | RATING | % |

| Belief in the Superiority of the Social Structure in the Ingroup | Above Average | 65% |

| Degree and Manner by Which Personal Goals Are Identified with National Goals | Low | 36% |

| Judgments of the Competence of National Leaders | High | 85% |

| Belief that Resources Are Available to Hurl Back Any Threats to the Ingroup | High | 77% |

| Confidence in the Permanence of the National Goal | Average | 52% |

| TOTAL | Average | 63% |

Table 1: Basic Factors of National Morale in the Russian Federation

Tallying the six factors of governance from the World Bank, national morale, and state fragility equally (eight metrics in total), the resiliency of the Russian Federation is estimated at 23.89%, with obviously weak and below-average governance factors but coupled with above-average national morale.[13] This dichotomy between weak governance combined with above-average patriotism indicates a ripe possibility for increasing resiliency in the Russian Federation but lesser opportunities, possibly, for resistance to opposition to the existing governance in the current environment.

Measuring the Potential for External Support to Putin’s Resiliency

A variety of external actors have an interest in the stability of the Russian Federation. This is due to several factors including abundant natural resources, Russia’s geostrategic position, its massive nuclear arsenal, and a desire to maintain Russia’s role as an antagonist to the current international order. Consequently, external support for the Putin regime could include China, Iran, and North Korea but also possibly European states and even the United States. In other words, external support for the Putin regime’s resiliency has real incentives that align with the national security interests of an eclectic group of diverse nations. We have determined the potential success of external support for the Russian Federation’s resiliency on three factors: (1) the strength of Putin’s diplomatic relations, (2) the self-reliance of Russia in terms of meeting its human security obligations in the absence of nonviolent assistance, and (3) the self-reliance of Russia in meetings its national security requirements in the absence of violent aid.

While the United States and much of Europe have imposed sanctions on Russia and provide lethal aid to the defense of Ukraine, in the long term, these same countries could attempt to reinforce the resiliency of governance in Russia in the future (or at least should maintain contingency plans to do so).[14] Meanwhile, North Korea, China, and Iran all have interests in a stable Russian Federation as well, and each of these has provided diplomatic support to Russia following its invasion of Ukraine and is likely to continue to do so.[15] Subjectively, the possibility of an external support strategy for Russian stability is high, estimated at 75%.[16]

Today, Russia appears self-sufficient in terms of meeting its human security obligations without the need for nonviolent aid. At its peak in 2007, the United States provided $1.6B in aid, almost all of it delivered to the energy and military sectors to ensure the safety of Russian nuclear programs. Since 2019, U.S. nonviolent aid to Russia has dropped precipitously, with only $110,000 in 2023 for wildlife conservation programs.”[17] As opposed to needing assistance, Russia has a recent history of contributing external support to the stability of other nations. In 2017, Russia contributed to large-scale developmental assistance programs with “the World Bank Group, the United Nations, major global initiatives, and special-purpose funds” totaling $1.18B.[18] Based on the Putin regime’s self-reliance in meeting the human security requirements of the Russian population, the Russian Federation appears a good candidate for additive stability efforts made by external supporters, with success estimated at 75%.[19]

Like its strong economic factors, Russia has demonstrated self-reliance in terms of national defense. Instead of importing lethal means, Russia has developed into one of the world’s largest exporters. In 2011, Russia provided military sales to 35 countries and nearly matched the arms export material of the United States. Starting in 2019, however, Russian defense industry sales have fallen sharply, particularly after the invasion of Ukraine, which isolated Moscow from some of its former customers. While Russia’s most important importers of lethal means remain China and India, it has also expanded its relationship with others like Turkey and Indonesia.[20] In the short term, the Ukraine War has forced Russia to import war materials from North Korea and Iran, but the Federation will likely continue to produce most of its security needs. With a self-reliant and world-class capacity, external support to Russian military security remains a sound wager with an estimated 75% chance of successfully increasing resiliency.[21]

Averaging all three metrics (Russia’s bilateral relations with potential sponsors, its innate ability to secure human security requirements, and its ability to arm, train, and equip its military) to an external actor choosing to bolster the Russian Federation’s resiliency equates to 75%, which makes this foreign policy decision decisive if the stability of the regime remains the desired end state. China, in particular, has the resources and proximity to effect positive strength to Putin’s Russia if needed, as a counterbalance to the aspirations of the West.

Measuring the Potential for Resistance in the Russian Federation

Over the past two decades, nonviolent and violent resistance in Russia has proven endemic. Between 2019 and 2024, 6,063 acts of violence occurred inside Russia with 1,452 fatalities. In the same period, eleven significant nonviolent protests mobilized in Moscow, four of which garnered a violent response from the regime.[22] Five of the eleven protests lasted longer than a month and one had more than 100,000 participants. Terrorist acts in Russia have proven historically horrendous. Between 2015 and 2020, the Global Terrorism Database records 157 acts of terrorism, perhaps the most predominant during this period conducted by the Caucasus Province of the Islamic State (IS-CP).[23] While IS-CP activities have diminished since 2017, Islamic extremism in opposition to the Russian Federation remains a serious threat to its internal security. Recently, in March 2024, the attack by ISIS-Khorasan at the Crocus City Hall in Moscow killed over 130 people.[24]

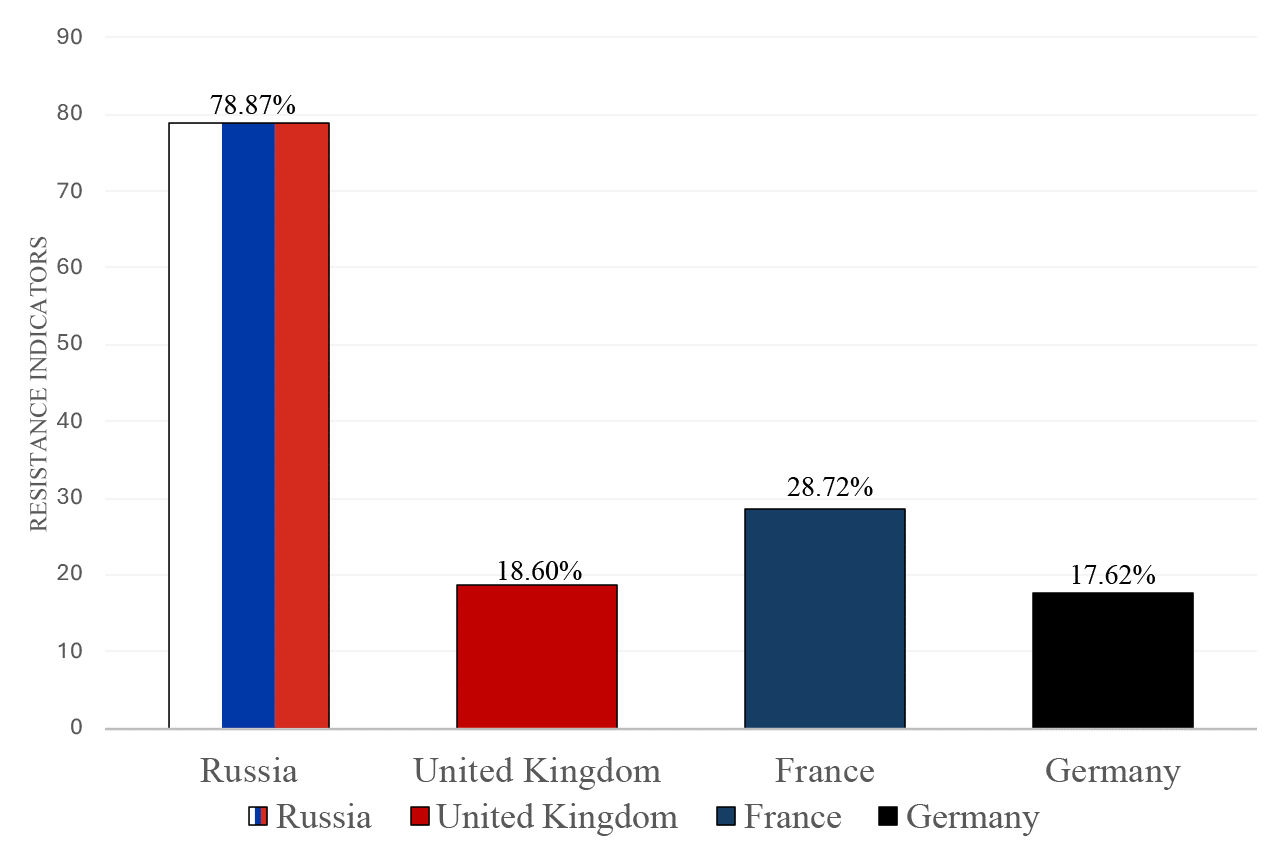

Objective data exist to measure the potential for internal resistance to current governance in the Russian Federation. We start with data derived from the Global Economy. This data ranks Russia in comparison with other nations, with 0% indicating little to no potential resistance to authority and 100% indicating the highest. Using this dataset: (a) in terms of current governance not adhering to the rule of law, 87.05%; (b) in political instability, 82.90%; (c) in the perception of the Federation not controlling corruption, 77.40%; (d) in a poor record on political rights, 86.17%; (e) in not respecting civil liberties, 84.57%, and (f) in its inability to regulate the shadow economy, 71.52%.[25]

For additional indicators, we evaluate liberty, crime, and food security. Vision of Humanity maintains a global peace index which places Russia as 158 out of 163 (or 96.93% unpeaceful in comparison with others).[26] Also, Freedom House ranks Russia as categorically “unfree” and one of the worst at 87% in comparison with others.[27] In terms of organized crime, Russia ranks the 19th worst among 193 states (placing it in the 90th percentile).” Lastly, food insecurity does not appear a relevant factor in the Russian resistance environment, assessed as a 25% potential contributor.[28] Averaging all nine of the preceding data figures equally, the Russian Federation scores high in resistance potential at 78.87%, implying ample opportunity for resistance to change or reform current forms of governance. The following figure illustrates Russia’s resistance potential in comparison with other European states.

Figure 1: Comparison of Russian Resistance Potential with the UK, France, and Germany[29]

In comparison with the United Kingdom, France, and Germany, Russian resistance potential is over two and a half times that of France, and over four times that of the United Kingdom and Germany. The Russian Federation exudes corruption, crime, unrest, and oppression far more than its neighbors in Europe and appears ripe for resistance.

Measuring the Potential for External Support to Resistance in Russia

In this last step of phase one, we analyze the potential success of an external actor in supporting Russian resistance to the Putin regime. While the United States maintains diplomatic relations with the Russian Federation, it also lists Russia as a competitor and an antagonist to the current world order in its National Military Strategy.[30] Considering Russia’s unfriendly and confrontational relations with the West, we rank the Russian Federation as a possible target of external support to resistance from an adversary as 100% plausible.[31]

The historical case study analysis completed by the Study of Internal Conflict at the Army War College poses four important questions to indicate the possible success or failure of an insurgency.[32] (1) Firstly, 15% or more of Russia’s population does not identify as a citizen of the state. The answer to this is clearly no, as an opinion poll in 2024 revealed “94% expressing pride in their identity” as Russians.[33] (2) Secondly, 15% or more of the population does not acknowledge the legitimacy of the regime. With 85% of Russians approving of Vladimir Putin, it remains clear that most Russians find the regime legitimate.[34] (3) 15% or more of the population have meaningful communication with a resistance movement. No violent resistance groups currently have sustained communication to this extent.[35] (4) Sanctuary exists for an armed component of resistance in a neighboring state. The answer here is likely no. Russia could be expected to use economic, military, and diplomatic means to ensure any Russian guerilla movement could not move back and forth across international boundaries (cyber offers access across international boundaries previously unrealized, which could prove important and in need of further study).

Examining all the data points presented regarding resistance potential, we assess that external support to a Russian-based resistance movement within the Federation has a possible success rate of 33%, with nonviolent and cyber-centric movements offering distinct advantages over those utilizing violent methods but also vulnerable to violent suppression by the totalitarian regime.

Phase One: Summary

In summation of phase One, based upon the information presented, the Russian Federation can be judged as having fundamental flaws in its current resiliency, primarily due to its poor metrics in governance (24.46%). Meanwhile, strategic partners of Russia, particularly China, have a good chance to reinforce the resiliency of the Putin regime should they desire to do so (75%). At present, the potential for internal resistance to the Putin regime is high due to poor indicators of proper governance (78.87%). Simultaneously, external support for resistance appears possible but risky, with a 33% probability of success.

Phase Two: Identifying Russia’s Resistance Movements

While Russia has a low record of success regarding resistance movements, since the collapse of the Soviet Union, Russia has experienced civil unrest, generally emerging in waves, highlighting dissatisfaction with the government and its policies. From anti-corruption rallies to anti-war demonstrations, the country’s streets have echoed with the voices of dissent, despite the government’s stringent measures to curb such activities. During the period from 1990 through 2019, major outbreaks of Russian resistance mobilized six times, with only one success (the pro-democracy movement 1990-1991), a success rate in the post-Soviet period of 17%.[36]

Nonviolent Resistance

Despite the pro-democracy movement’s triumph, most Russians view the changes it brought as a disaster. During the Presidency of Boris Yeltsin, the new Russian Federation embarked on a series of radical economic and political reforms intended to transition Russia to a market economy and democratic governance. This period was characterized by widespread corruption, economic hardship, and substantial political instability – paving the ground for the rise of newcomers, and oligarchs, to take over a large portion of Russia’s economy and financial resources. Additionally, the vacuum of power left behind by the collapse of the Soviet Union triggered major disruptions to national security, including two generations of brutal wars in Chechnya, which further entrenched the perception that democracy has brought disorder and suffering.

Thus, for many Russians, the concept of democracy is indelibly linked with instability, economic collapse, and social unrest. The collective memory of the hardships endured during these periods has led to a preference for stability and security over the uncertainties of democratic change. This perspective is often reinforced by Putin’s narratives that any attempt to undermine the state’s authority, not only would destabilize the current affairs and livelihood of Russians, but it also could endanger Russia’s territorial integrity and its very existence. As a result, the idea of a stable and secure Russia, even under an authoritarian regime, is more appealing to many Russians than the perceived chaos of a democratic system. Understanding this historical context is crucial for comprehending the complexities of Russia’s political landscape and the deep-seated resistance to democratization efforts within the country.

Between 1999 and 2020, approximately 2.2 million people mobilized on more than a hundred occasions in nonviolent protests during Vladimir Putin’s dictatorship.[37] Between 2020-2024, eleven protests and demonstrations occurred, which add up to an additional 187,302 protesters seeking changes in governance.[38] In total, during Putin’s regime, nonviolent protesters opposed to his leadership or policies totaled 916,876 mobilized. For contemporary events, we highlight a few recent waves against the Putin Regime, starting with the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2014.

First Invasion of Ukraine: Anti-War Protests (2014)

The annexation of Crimea in March 2014 sparked a new wave of demonstrations, this time focused on Russia’s aggressive foreign policy. Although smaller in scale compared to previous protests, these anti-war rallies underscored a growing unease with the Kremlin’s actions on the international stage. Protesters hit the streets in Moscow twice in March and once in September, totaling around 112,000.[39] The government’s swift crackdown on these protests reflected its zero-tolerance approach to dissent.

Anti-Corruption Protests (2017-2018)

The fight against corruption took center stage in March 2017 when opposition leader Alexei Navalny published a damning report on Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev’s alleged corrupt practices. This investigation ignited nationwide protests, drawing thousands into the streets and resulting in mass arrests. The momentum continued into June 2017, with further demonstrations on Russia Day seeing significant police action against protesters. Navalny’s influence persisted into 2018, as he called for a boycott of the presidential election after being barred from running. January 2018 saw supporters rallying in Navalny’s favor, demanding a fair electoral process and transparency. Putin arrested Navalny in May, and protesters emerged again throughout the country referring to Putin as Russia’s new Czar.[40] The total number mobilized during this period on ten occasions was around 122,000.[41]

Election Protests (2019)

In the summer of 2019, Moscow witnessed large-scale protests demanding fair local elections. Opposition candidates had been disqualified, prompting citizens to take to the streets in June, July, and August. The total number mobilized on nine occasions equates to roughly 97,000.[42] The authorities’ response was marked by mass arrests and police violence, revealing the state’s determination to maintain control over the electoral process.

Constitutional Changes (2020-2021)

The announcement of proposed constitutional changes in January 2020, which would allow Putin to potentially remain in power until 2036, triggered a new series of protests. Demonstrators expressed their frustration with what they saw as an erosion of democratic principles in Russia. The return of Alexei Navalny to Russia in January 2021, and his immediate arrest, led to some of the largest protests in recent memory. Thousands took to the streets across the country, demanding his release and an end to political repression. The government’s response was severe, with widespread detentions and a heavy police presence. Total numbers were around 122,000 mobilized.[43]

Second Invasion of Ukraine (2022-2023)

The invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 brought a new wave of anti-war protests. Demonstrators decried the military action and called for peace, facing significant repercussions from the authorities. Protesters numbered around 10,000.[44] Through March 2023, anti-war protests continued sporadically, although participation waned due to the heavy-handed crackdowns and severe legal consequences for demonstrators.

Nonviolent action between 2014 to 2023 reveals major activity by four primary organizations. (1) The Russian United Democratic Party (Yabloko) is currently led by Nikolai Rybakov. While representation remains small, Yabloko remains an official party in Russia and desires “a liberal, progressive, and a European perspective for Russia.”[45] (2) The People’s Freedom Party (Parnus) has a long history of dissent towards Putin and therefore subject to continuous attacks by the regime, including the assassination of its leaders. In May 2023, Russia’s Supreme Court dissolved Parnus as an official Russian party to ensure it could not compete in the 2024 election. Seeking sanctuary, Parnus’ President, Mikhail Kasyanov, left Russia in 2022 to live in exile in nearby Latvia.[46] (3) Russia of the Future remains an unregistered political party under the former leadership of internationally recognized activist Alexei Navalny. Navalny faced suppression, imprisonment, and recent execution by the regime.[47] It remains to be seen if Navalny is erected in martyrdom to mobilize resistance or if his death terminated the viability of Russia of the Future. (4) An interesting and budding political rival to Vladimir Putin’s regime remains the Communist Party of the Russian Federation (KPRF).[48] In apprehension, it appears Putin has begun to defraud KPRF of many votes.[49] Reporter Robyn Dixon for the Washington Post wrote that the KPRF is “starting to behave like genuine opposition” to Putin.[50] In summary, despite the disparate groups operating through legal activities directly or indirectly in opposition to the regime, nonviolent legal resistance appears fairly disunified in terms of cooperation with each other (i.e. there exists no united front).[51] While this might imply that these movements do not constitute a threat to the Putin regime, the violent suppression of most of these groups demonstrates that Putin views them as real threats to his power.[52]

Violent Resistance

A major factor contributing to Putin’s resilience is the paradoxical effect where violent resistance against the government can sometimes lead to Putin expanding his power. The Chechen resistance, a violent struggle for independence of the Chechnyan Republic (1994-2009), exemplifies this dynamic. Chechen insurgents directly challenged the Russian Federation’s control over the region. The resistance of the Chechen minority threatened the Russian national identity, leading to a rally-around-the-flag effect, where the general populace supported stronger measures. Putin’s administration used the war to introduce laws that enhanced the powers of law enforcement and security agencies, allowing for greater monitoring and suppression of opposition activities. These measures were often framed as necessary for national security, gaining broad public support despite their erosive impact on democratic freedoms. By framing the Chechen resistance as a dire threat to national unity, Putin was able to consolidate his power and extend his influence over the Russian state. The centralization of authority during this period set a precedent for how the government could respond to other forms of resistance, using similar tactics to bolster its resilience in the face of opposition.

The Chechen example highlights a broader pattern where resistance movements, particularly those involving minority groups, can inadvertently empower the government’s resilience. When the state successfully frames such resistance as a threat to national security, it can garner widespread support for measures that would otherwise be seen as severe. This dynamic creates a double-edged sword: while resistance seeks to challenge the government’s power, it can also provide the government with the justification it needs to strengthen its control.

Understanding this paradox is crucial for formulating effective foreign policies and strategies to support opposition movements in Russia. Simply, while resistance against the Russian government is a necessary and legitimate response to authoritarianism, it is vital to recognize the potential for such movements to inadvertently strengthen the very regime they oppose. Any support for resistance must be carefully calibrated to avoid reinforcing the government’s narrative of threat and justification for increased repression. Strategic support for resistance must be nuanced and aware of these dynamics, aiming to undermine the government’s power without reinforcing its claims of defending national integrity and security.

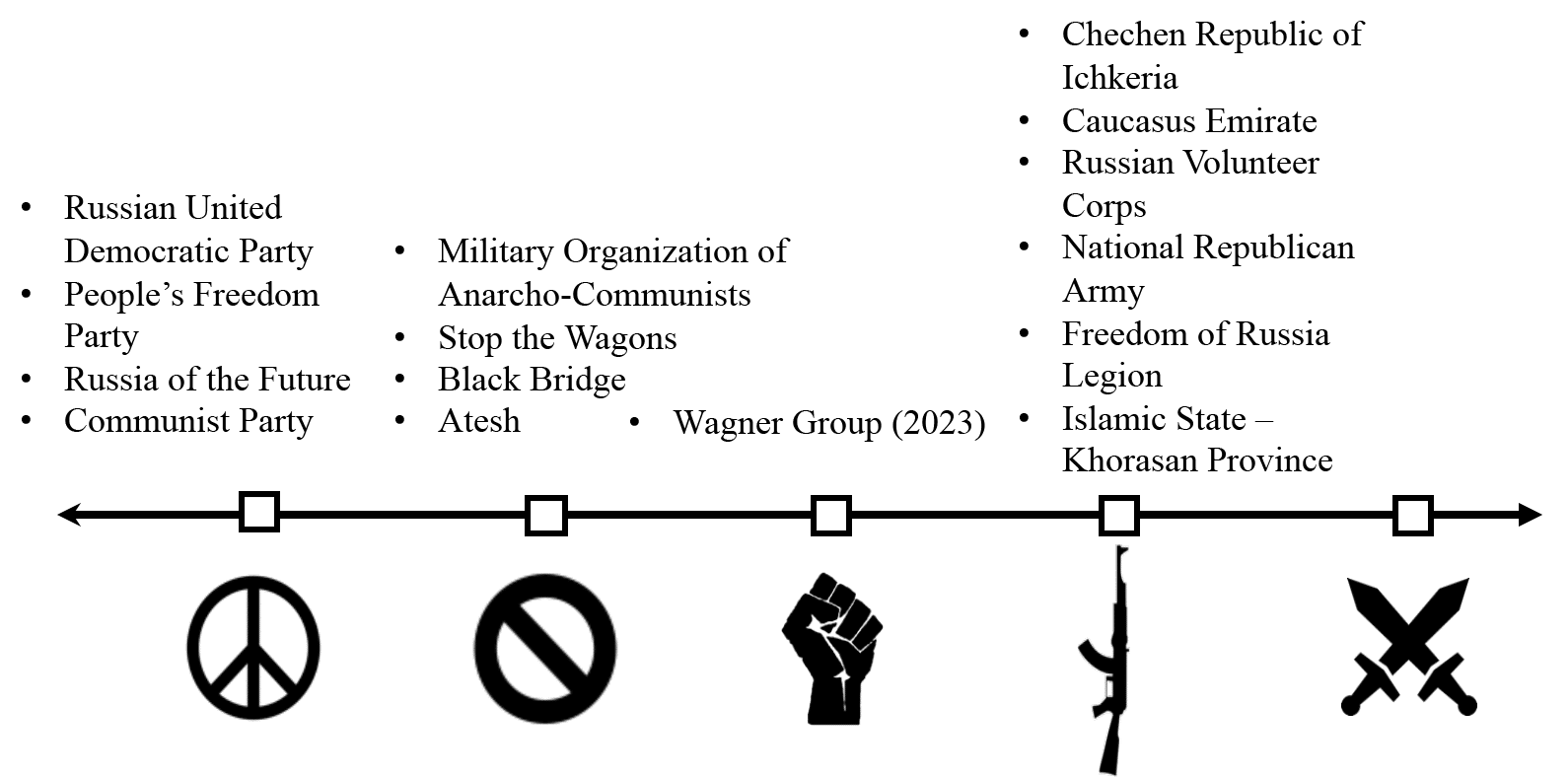

While generally unsuccessful in creating change, several nonviolent groups utilizing illegal methods, as well as organizations using violent resistance, have been pervasive in Russia. Since Putin’s ascendency in 1999 through June 2024, 19,459 Russians have died in internal hostilities (the vast majority occurring in Chechnya).[53] Three nonstate groups remain significant: (1) the Chechen Republic of Ichkeria, a loosely organized coalition with continued ambitions for Chechen independence; and (2) the Caucasus Emirate, an umbrella term for several armed groups in the North Caucasus which have lain fairly dormant for several years, with the exception of one offshoot, Islamic State – Caucasus Province.[54] (3) Another Islamist resistance group includes Islamic State – Khorasan Province, which conducted the attack on a Moscow concert hall with 93 people killed and 145 wounded on 22 March 2024.[55] Several other resistance organizations in Russia have emerged following the invasion of Ukraine in 2022. The largest includes (4) Wagner Group, which conducted a short but prominent rebellion under the leadership of Yevgeny Prigozhin in June 2023.[56] Smaller groups include (5) Military Organization of Anarcho-Communists, which practices illegal forms of resistance, particularly disseminating subversive propaganda, sabotaging railways in Russia and Belarus, and conducting twenty arson attacks on military registration and enlistment offices.[57] Another resistance group choosing illegal methods includes (6) Stop the Wagons, an anti-war organization that has used explosive devices on railways.[58] Similarly, (7) Black Bridge has targeted Russian government offices, including the arson of a Federal Security Service building in March 2023.[59] Another illegal and subversive organization is (8) Atesh (meaning “fire” in Tatar), whose agents collect information on Russian military activities in Siberia and send that intelligence to Ukraine. In contrast, there are several insurgent groups directly attacking Russia as paramilitary organizations, three have politically unified while fighting in Ukraine in the Irpin Declaration which includes (9) the Russian Volunteer Corps, (10) the National Republican Army, and (11) the Freedom of Russia Legion.[60]

Irregular Support

Under Putin’s dictatorship, he has collaborated with several nationalist and illicit organizations to implement his ambitions abroad and suppress dissent at home. The full array of these irregular cohorts was exhibited, and invigorated, during the Russian annexation of Ukraine in 2014, where paramilitary groups, illicit organizations, and private military companies took a primary role in the front lines. (1) Wagner Group continues to work for the Kremlin as a counterforce to the liberal order, with activities in Libya, the Central African Republic, Mali, Mozambique, Sudan, Madagascar, Cameroon, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Zimbabwe, Kenya, Venezuela, and others.[61] Wagner continues to fight alongside the Russian Army in Ukraine. Putin has also collaborated with nationalist paramilitary organizations that suppress Russian dissent at home, act as auxiliaries to fight in Ukraine and support U.S. and European white nationalist extremist groups. A major nationalist paramilitary organization includes the (2) Russian Imperial Movement (RIM), a monarchist Orthodox movement, which supported Russian resistance in Donetsk, Ukraine (2014-2022), fights alongside the Russian Army in Ukraine (2022-present), and was designated a terrorist organization by the U.S. Department of State in 2020 (particularly for its collaboration and training with white supremacist groups internationally).[62] In his early administration, Putin treated the (3) Russian mafia (Vory) as a criminal organization, but the war in Ukraine has witnessed a growing collaboration between the two.[63] Wagner Group certainly recruited members of Vory from Russian prisons to fight on the front lines. More disturbing, Vory wields a strong and effective global underground, and Russia is utilizing it “as an arm in its intelligence apparatus,” including the carrying out of targeted assassinations abroad.[64] To surmise, Wagner Group, Russian Imperial Movement, and Vory should not be considered simply proxies of the Putin regime, as they have their own motives and ideologies, but they do currently act as his grey-zone allies.

Phase Two: Summary

The following figure illustrates prevalent Russian resistance movements across a resistance continuum, including (from left to right) nonviolent legal, nonviolent illegal, rebellion, and insurgency. Additionally, on the far right of the scale, no known insurgent groups have yet to rise to the level of belligerency by exhibiting the functions of an opposing state.[65] Irregular organizations supporting the Putin regime are not illustrated (Wagner Group, Russian Imperial Movement, and Vory).

Figure 2: Diagram of the Russian Federation’s Resistance Continuum

Phase Three: Assessing Russia’s Resistance Movements

After identifying resistance movements along a continuum, we present a deeper investigation into Russia’s communist party – KPRF. In assessing the Communist Party, we examine five attributes: (1) actors, (2) causes, (3) environment, (4) organization, and (5) actions.[66]

The Actors in the Communist Party of the Russian Federation (KPRF)

The actor category includes types of leaders in KPRF, its participants, how KPRF interacts with the population, its relations with other resistance movements, and sources of external support. As background, KPRF was founded in 1993 as a successor to the Communist Party of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic when the Soviet Union fell. KPRF remains the viable and overt political opposition to United Russia and the Putin regime.[67] It is the second-largest party in Russia, representing 57 of the 450 delegates in the State Duma. The current and long-standing General Secretary remains Gennady Zyuganov, who assumed office in 2001. Zyuganov had a strong chance to win the presidency in 1996 but sought to nationalize major industries. In response, several Russian oligarchs made the “Davos Pact” that same year to fund propaganda against him.[68] Nevertheless, Zyuganov nearly won with 40% of the vote, demonstrating great popularity.[69] He ran again for President in 2008, showing less than half his previous popularity with 17.76% of the vote. Still retaining at least some political strength, Zyuganov’s current platform rests on three primary principles of “Stalinism, nationalism, and social-democratic paternalism.”[70]

Zyuganov’s leadership role appears that of an agitator. While he supports the current war in Ukraine,[71] Zyuganov has demonstrated harsh criticism of Putin as well. In 2008, he made the following remarks to the Central Committee of the Communist Party: “The ruling group has neither notable successes to boast of, nor a clear plan of action. All its activities are geared to a single goal: to stay in power at all costs…Its social support rests on the notorious ‘vertical power structure’ which is another way of saying intimidation and blackmail of the broad social strata and the handouts that power chips off the oil and gas pie and throws out to the population in crumbs, especially on the eve of elections.”[72] Scholar Katlijn Malfliet describes KPRF as a mutant, an adaptor, and a chameleon-like actor, facilitating change in Russia as it simultaneously evolves to the conditions.[73] It has demonstrated great resiliency, clinging to communist ideals of a foregone era while participating in a strangely semi-democratic form of governance in which communism now speaks as the minority.

KPRF has three major ideological lines: (1) a Marxist-Leninist orthodoxy, espousing socialist ownership of the means of production in order to redistribute wealth to the people; (2) a national-socialist and clearly anti-western agenda; and (3) a social-democratic discourse highlighting the need for popular sovereignty by means of free and fair elections.[74] However, over the past decade, the third line of effort (social-democratic discourse) has become more prominent, with frequent calls for election transparency, increased rule of law, and respect for the constitution.[75] As such, KPRF serves with increasing frequency as opposition to the corruption of the current regime, while it simultaneously plays a game of survival, which it has done adeptly since the fall of the Soviet Union.

In terms of demographics, KPRF represents an estimated 12% of voters. In the regional committees, 54% of the Communist Party leadership is over 60 years old. This figure does not imply that KPRF consists of soviet era politicians, as 55% of the regional leadership started their careers in the party after the dissolution of the USSR. All are highly educated with 99% college graduates. KPRF includes many professional lawyers, representing 29% of the regional committees. Only 9% of this leadership is female.[76]

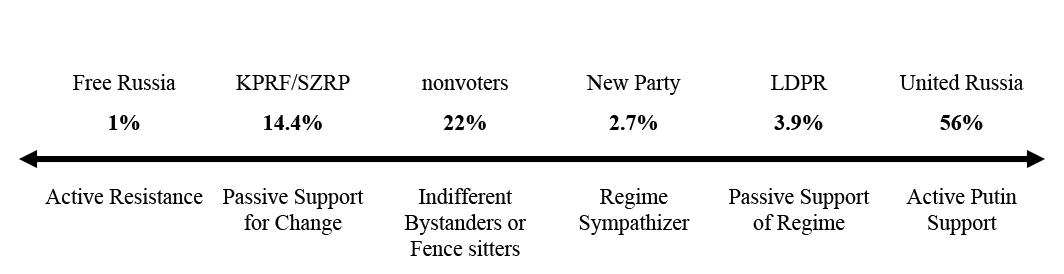

We explore here how viable KPRF is to the Russian ingroup within the general population. Jonathon Cosgrove and Erin Hahn propose a scale, with participants in the resistance on the left, loyalists to the regime on the right, and a spectrum of popular support in the middle.[77] The following figure illustrates current support for the Putin regime and resistance to it based on election results in 2024. Active resistance includes all banned parties in Russia, of which there have been dozens since 1991. The most prominent and recent ones include Russia of the Future (dissolved in 2021) and several others, all considered resistance participants. On the surface, these numbers appear about 1% or less of the population (subsurface undergrounds remain undetermined). Five active parties sitting in the Duma include: (1) KPRF, considered passive supporters of resistance; (2) A Just Russia for Truth (SZRP), also included as passive support for resistance (particularly considering KPRF and SZRP have discussed merging in 2022);[78] (3) the New People (NP) party is expected to behave as Putin sympathizers, (4) Liberal Democratic Party of the Russian Federation (LDPR), considered passive support for Putin; and (5) United Russia, considered Putin loyalists. Additionally, 22% of Russians did not vote in 2024, and are listed as indifferent bystanders or fence-sitters.[79]

Figure 3: Scale of Popular Support for and Against Resistance

While elections illustrate a scale of opposition to and support for the current regime, a large segment of the Russian population continues to regard Putin as a hero. This cult of personality has varied from 60% of the population considering Putin a hero in 2008 and dropping to 38% in 2021.[80] Polling over the past two decades indicates that Russians remain extremely patriotic and nationalistic, with two prominent communists, Stalin and Lenin, rating them as the “most outstanding people of all time.”[81] Russians hold deep contempt for traitors, greed, and dishonesty, all three characteristics that could feed a negative narrative against the Putin regime.[82] Thus, the espoused values and platform of the Communist Party should remain appealing to most Russians, and given the right conditions, the popularity of KPRF could rise indirectly in opposition to United Russia, while direct opposition to Putin remains a challenge.

KPRF’s relations with other resistance organizations vary. We regard those not in the ingroup as incompatible with KPRF, including the Chechen Republic of Ichkeria, the Caucasus Emirate, Islamic State – Khorasan Province, and Russian paramilitary groups in Ukraine. In contrast, A Just Russia for Truth (SZRP) presents an opportunity for KPRF to expand its ranks. Other underground opposition organizations could align with KPRF, but those desiring change to align with Western Europe would likely find those ideals incompatible.

KPRF attempts to align with communist and socialist movements worldwide, a continuation of the type of powerful alignments that evolved in the early twentieth century. KPRF attends the International Meeting of Communist and Workers’ Parties annually. In 2023, this meeting included delegations from 54 nations.[83] The communist and socialist front worldwide remains quite significant and provides agency and legitimacy to these ideologically aligned movements. While communism has generally declined since the fall of the Soviet Union, several nations continue to uphold communist ideals, the most powerful of which is China. Other organizations, particularly those acting as resistance within Europe, might prove important in garnering external support for KPRF. Meanwhile, overt support from Western governments could prove subversive to the KPRF cause.

Cause of the Communist Party of the Russian Federation.

KPRF remains a Marxist-Leninist organization, espousing social justice, collectivism, freedom, and equality.[84] Its ideals are directly spelled out by its program and approved by the KPRF Congress. Socialism remains the evolved and fair system of human governance. Capitalism is viewed as unjust, which the West forced upon Russia when it subverted the USSR and resulted in catastrophe.[85] The KPRF seeks to build a renewed and advanced 21st-century socialism in Russia. The principles of KPRF have some alignment with the domestic and foreign policies of Putin, in that it maintains a nationalistic and anti-Western ideology that espouses the restoration of the Russian people as a great world power. However, KPRF adopts a socialist Russia, one in which private ownership, particularly of natural resources and industry, is severely curtailed, and that runs counter to a system of powerful oligarchs backing the Putin regime.

Several scholars have begun to recognize KPRF’s growing schism with the Putin regime. As stated by political scientist Oleksiy Bondarenko in 2023, “Although the party is considered to be a member of the so-called ‘loyal’ opposition, the increasing volatility of the party system and growing political instability have implications for future relations between the KPRF and the regime.”[86] In contrast to the direct support of Putin, the KPRF appears to vacillate between direct opposition to regime proposals and/or bargaining indirectly for concessions. Opposition has grown more frequent, primarily because for KPRF to remain a viable political entity, it needs popular support, while election fraud erodes its representation. Hence, as Putin attempts to consolidate power by co-opting the democratic process, this inevitably sets him at odds with the Communist Party.

The Resistance Environment in the Russian Federation.

Assessing the resistance environment for KPRF includes the evaluation of environmental, socio-political, and relationship factors. KPRF will likely continue to utilize legal (and sometimes illegal) but nonviolent activities as opposed to Putin’s regime. Bondarenko states that “KPRF is not only the most likely to engage in street activism and protests but is also the party with the most autonomous network of activists at the sub-national level.”[87] As a nonviolent resistance, the physical geography of Russia has less impact on KPRF’s potential success, making the space and information domains the most influential. The cyber domain remains essential, particularly for maintaining KPRF’s messaging, recruitment, and propaganda.

Russians’ access to the internet (or RUNET) has skyrocketed. In 2008, 38 million Russians could access the internet (or 27% of the population).[88] By 2024, that estimate has risen to 132 million or 88% of the population.[89] Most scholars agree, however, that television remains the primary information source for Russians. When polled, 86% consider television their primary medium for news; however, only 56% of those say they trust the news provided on television.[90] As such, RUNET remains primary as an alternative means of getting information and of particular use for resistance messaging. Under the Putin regime, Russia has instituted “an intricate multi-layered system of surveillance and excessive control over online content,” all under the guise of protecting national security.[91] Russian users have resorted to virtual private networks (VPN) to hide their signatures. In April 2022, one Russian VPN provider (AtlasVPN) recorded a 2,000% increase in usage.[92] In March 2024, Putin banned VPN advertising, but VPN companies continue to operate under Russian legislation.[93] For now, KPRF is harnessing RUNET for its purposes while staying in compliance with regulations.

Since its inception in 1993, KPRF has skillfully navigated Russia’s socio-political environment, surviving when most Western and even domestic pundits believed communism was dead. It has survived by remaining in compliance with the Russian constitution and reserving its nonviolent actions (like unscheduled protests) for specific, and popular, agenda items. KPRF has also wedded its narrative to a belief in Russian exceptionalism, or greatness, which nests well with traditional ideals of Russian foreign policy, going back to the Czars period.[94] As such, it has harnessed Russian patriotic history, including the Soviet era – to a greater extent than its competitors. Communism, however, does not generally appeal to the Russian business sector. In a positive economic climate, one might expect KPRF membership to remain stagnant. However, should the Russian economy suffer, the KPRF’s socialist agenda may increase its popularity.

KPRF leadership and membership offer an excellent case study for social network analysis and a scientific approach to understanding its relationships domestically and internationally. One scholar, Jan Matti Dollbaum, conducted a study on KPRF’s use of social media to politicize grievances towards Russia’s pension reform legislation in 2018. Both KPRF and Aleksey Navalny’s Free Russia party sought to block these measures through legal forms of resistance, and both utilized the platforms of Twitter and VKontakte (Russia’s version of Facebook) to mobilize protest.[95] This demonstrates that KPRF can align its narrative at times with outspoken critics of the Putin regime.

Organization of the Communist Party of the Russian Federation

Jonathon Cosgrove and Erin Hahn generally categorize resistance organizations into two bins: (1) mass organizations and (2) elite organizations.[96] KPRF obviously resembles a mass organization. It claims 160,000 members and organizes its activities with a headquarters in Moscow. It maintains a Central Committee, made up of 188 members. It has 89 regional committees headed by first secretaries. Gennady Zyuganov serves as both the General Secretary of the party itself as well as its parliamentary leader in the Duma.[97] In the 2021 elections for the State Duma, exit polling suggests that only 55% of people voted, but that 24% of them voted for the KPRF, only slightly less than United Russia with 38%.[98] If so, KPRF currently retains more popularity in Russia than its representation in the Duma suggests. Currently, KPRF has 57 of the 450 seats, which equates to 12.7%, while United Russia has 325 seats (72%).

KPRF utilizes several methods to communicate with its members and the general population. Unlike illegal organizations, it retains “legally guaranteed airtime before elections and press coverage of its parliamentary activities.”[99] Additionally, it leverages social media, with posts coming directly from the party headquarters and not from individual accounts.

KPRF also advocates for a youth movement called Movement of the First. Although President Putin officially appointed the leadership and funding for the Movement of the First, KPRF argues that this organization traces its lineage to the Soviet Union’s Young Pioneers. KPRF is attempting to indoctrinate and recruit future communists from this group.[100] In fact, both Gennady Zyuganov and Vladimir Putin can be seen meeting with these young people at various events, essentially competing for influence.

Resistance movements can be sub-organized in a myriad of ways. In most military doctrines, these can include (a) a public component, (b) an auxiliary, (c) an underground, and (d) an armed component.[101] The Communist Party likely wields three of these currently: a public component, an auxiliary, and an underground. The public component is the outward workings of the party itself as discussed. In terms of an auxiliary, the party has 160,000 members but millions of supportive voters behind secret ballots. From 2014-2022, KPRF successfully organized a communist underground in Donetsk, Ukraine.[102] The Donetsk People’s Republic communist organization merged with KPRF following Russia’s annexation of the region in 2022. KPRF has the history, capacity, ideology, and tradecraft to effectively organize an underground if desired.

Actions of the Communist Party of the Russian Federation

As previously discussed, KPRF seeks nonviolent but legal forms of resistance to establish its goals of a democratic and socialist Russia. It leverages its voting power to assure concessions from the Putin regime, particularly to placate its constituents regarding social welfare programs. When needed, it harnesses nonviolent action to protest and harness public support. It consistently utilizes information operations domestically and internationally to garner support for its cause. It walks a thin line between passive protest of the Putin regime and acquiescence to United Russia.

Phase Three: Summary

In phase three, we summarized one of the fifteen resistance organizations identified in phase two. The Communist Party of the Russian Federation (KPRF) comprises a substantially sized organization with a discernable counter-vision for Russia to that of President Vladimir Putin’s regime but also some solidarity in terms of nationalism and re-establishment of a greater Russia. KPRF has broad support and opportunities to expand its influence, particularly in coalition with A Just Russia for Truth. The poor performance of Putin’s military in the current war in Ukraine, as well as the inevitably negative economic fallout for Russia after it, offers opportunities for KPRF to expand its representation in the State Duma. Any actions by the Putin regime to hijack the democratic process in Russia will inevitably lead to a clash between the two.

Phase Four: Options in Support of Resilience or Resistance

In phase four, we utilize the data gathered in the previous three phases to better inform the foreign policies of nation-states regarding the Russian Federation. The typical suggestion for action formulates a proposal for one of three options: (a) support the resilience of the Putin regime, (b) support resistance to the Putin regime, or (c) choose to support neither, but prepare the environment for future policy.

Supporting the Resilience of Putin’s Russia

Two nations overtly support the resiliency of Russia – Iran and North Korea, as both sell vital arms and equipment to fuel Russia’s war in Ukraine. Meanwhile, China is providing tacit support to Russia, and India is continuing military and economic collaboration, maintaining an overt alliance. Russia maintains more diplomatic support globally, particularly in Africa.[103] Meanwhile, the West has instituted broad sanctions to stifle the Russian economy, as well as giving billions of dollars of military support to Russia’s rival in Ukraine. European opposition to the Putin regime remains strong, but the support of the United States in funding the war in Ukraine appears to be waning. Compounded by a war weariness of two decades fighting in Iraq and Afghanistan, 45% of Americans polled in 2024 believe the U.S. is spending too much in Ukraine.[104] Many pundits believe the U.S. presidential election in November 2024 will decide future U.S. policy towards Russia.[105]

There remains the option for the West to support Russia’s resilience, but little appetite for it, particularly for strengthening institutions in Putin’s Russia. The current approach concentrates only on the near-term consequences of holding Russia accountable for invading Ukraine – essentially building a broad coalition to ensure Russia cannot oppose the international order. The long-term implications of Russia’s resiliency, or lack thereof, have not been given much consideration in Western foreign policies yet remain vital to European and global security. The grand strategy should consider the implications of a resilient Russia versus a fragile one and offer a contrarian foreign policy option to deliberate.

Supporting Russia’s Resistance

While the United States and most European nations remain in staunch opposition to the Putin regime, they have not offered external support to domestic resistance to him. Supporting the war in Ukraine and supporting domestic resistance to Putin in Russia remain two distinctly different, although complementary, foreign policy options. Western countries might consider sponsoring either nonviolent or violent forms of Russian resistance. Despite the applause in Western media sources for activists like Alexei Navalny, anyone deemed as pro-West has not proven popular in Russia. Violence includes insurgent groups in the Caucasus region, but the tactics utilized by many of these opposition movements remain incompatible with Western values. Additionally, the Russian paramilitary groups operating in Ukraine may appear acceptable, but they are too small to be considered serious opposition, and they are Western-leaning – an unpopular characteristic for Russian support.

KPRF proves an intriguing option for Western support. On the one hand, it is the sole organization currently wielding the potential to oppose Putin. On the other hand, the United States and other nations placed sanctions on KPRF leaders Gennady Zyuganov and Ivan Melnikov following the invasion of Ukraine in 2022. Western policy has not progressed to distinguish a difference between Putin’s regime and its most powerful opposition – KPRF.

One strategic approach might be to support nationalist movements within Russia, not just KPRF but possibly others. Yevgeny Prigozhin’s rebellion with Wagner Group in June 2023 exemplifies the potential of such organizations to challenge the Putin regime. This recommendation is grounded in several key considerations. First, nationalist movements have strong ties with a significant portion of the Russian population, which grants them some support. This grassroots backing makes them a potent force for change, capable of mobilizing segments of society against the current regime. However, while supporting nationalist movements within Russia might seem like a strategic way to weaken Putin’s regime, this approach comes with significant drawbacks. A major concern is the problematic ideologies these groups often espouse, including racism, anti-Semitism, and xenophobia. Additionally, provoking instability in Russia without a clear objective could prove a disastrous course of action with unanticipated results.

Choose to Support Neither but Prepare the Environment for Future Policy

While supporting Putin’s regime appears undesirable, aiding resistance poses significant risk. In the absence of a strategy to support resilience or resistance, Western foreign policy should avidly attempt to prepare the environment for a positive transition to future foreign policy. Despite the fifteen Russian resistance movements identified, Vladimir Putin remains strongly entrenched as the leader of Russia, with no real opposition identified in our data as capable of replacing him. Consequently, maintaining dialogue with Putin allows for a future policy in which strengthening Russian institutions makes sense. Conversely, the West should maintain and open dialogue with the many resistance organizations in Russia. Maintaining sanctions on the primary opposition party in the State Duma (KPRF members) might not comprise the best long-term strategy in terms of dialogue with the opposition. As several European countries endorse socialist perspectives, making inroads with KPRF collaboratively could prove constructive or at least identify more possibilities.

Conclusion

Our analysis of Russia in terms of resilience and resistance highlights significant weaknesses in governance under Putin’s Russian Federation, with resistance potential remaining high. However, support for resistance movements has a low probability of success, whereas bolstering Putin’s resilience may offer strategic possibilities. Of the many resistance groups, none provides an ideal alternative to Putin. Nonviolent resistance has been suppressed, political opponents eliminated, and violent opposition met with military force. Moreover, Putin has increasingly collaborated with militant and illicit groups to counter dissent and challenge opponents abroad. This volatile domestic environment pushes Putin toward aggressive foreign policies to placate a largely nationalistic population, making positive change in relations with the West unlikely during his rule.

As outlined in this paper, nationalist movements in Russia possess significant potential to challenge the government. However, their diverse and decentralized nature makes them difficult to analyze or support as a coherent entity. By contrast, the Communist Party of the Russian Federation (KPRF), with its centralized structure, offers a clearer subject for analysis, using established metrics. While the KPRF remains the most organized and potentially viable alternative, it is far from an appealing choice. These factors warrant Western concern about the future trajectory of Russia.

Robert S. Burrell is a Senior Research Fellow at the Global and National Security Institute, University of South Florida. He previously served as Assistant Professor at the Joint Special Operations University and Editor-in-Chief of Doctrine for Special Operations Command. Dr. Burrell also held a diplomatic post in Australia and spent 12 years in the Asia-Pacific region. He holds a Ph.D. in History from the University of Warwick and advanced degrees in National Security and History.

Arman Mahmoudian is a Research Fellow at the Global and National Security Institute and an adjunct faculty member at the University of South Florida. He holds a Ph.D. in Politics and International Affairs from the University of South Florida, a Master’s in International Relations from Russia, and a Bachelor’s in Law from Iran. He is a member of the editorial board at the Joint Special Operations University and has published widely on Middle Eastern and Russian affairs.

[1] CIA World Factbook, https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/, accessed May 13, 2024.

[2] Richard Sakwa, “Putin’s Leadership: Character and Consequences,” Europe-Asia Studies 60, no. 6 (2008): 879–97, https://www.jstor.org/stable/20451564.

[3]“Gross Domestic Product,” World Bank, found at https://databankfiles.worldbank.org/public/ddpext_download/GDP.pdf, accessed on 13 May 2024.

[4] CIA World Factbook.

[5] The World Bank, “Worldwide Governance Indicators,” https://www.worldbank.org/en/publication/worldwide-governance-indicators, accessed April 2, 2024.

[6] Fragile States Index, https://fragilestatesindex.org/, accessed April 2, 2024.

[7] Delbert C. Miller, “The Measurement of National Morale,” American Sociological Review 6, no. 4 (August 1, 1941): 487–98. Ben Connable et al., Will to Fight: Analyzing, Modeling, and Simulating the Will to Fight of Military Units (Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2018). Ben Connable, “Structuring Cultural Analyses: Applying the Holistic Will-to-Fight Models,” Journal of Advanced Military Studies: Special Issue on Strategic Culture (2022): 153–67.

[8] Dina Meltz et al., “Generation Putin: Proud but Politically Disengaged Russians,” Chicago Council on Global Affairs, March 2024, https://globalaffairs.org/sites/default/files/2024-04/Generation%20Putin.pdf, accessed May 15, 2024.

[9] Ibid, 6.

[10] “Do You Approve of the Activities of Vladimir Putin as the President (Prime Minister) of Russia?,” Statista, April 2024, https://www.statista.com/statistics/896181/putin-approval-rating-russia/, accessed May 15, 2024.

[11] Nate Ostiller, “Poll: 77% of Russians Support War in Ukraine,” Kyiv Independent, February 7, 2024, https://kyivindependent.com/poll-77-of-russians-support-war-in-ukraine/, accessed May 15, 2024.

[12] Meltz et al., “Generation Putin.”

[13] These metrics do not include the Swiss Re Institute’s Resilience Index as it accounts for only 31 nation states.

[14] U.S. Department of State, U.S. Bilateral Relations Fact Sheets, https://www.state.gov/u-s-bilateral-relations-fact-sheets/, accessed May 20, 2024.

[15] Leo Chiu, “Explained: Who are Russia’s Allies? A List of Countries Supporting the Kremlin’s Invasion of Ukraine,” Kyiv Post, October 23, 2023, https://www.kyivpost.com/post/13208, accessed May 20, 2024.

[16] We considered the following in determining this percentage. If Russia had only adversarial or limited diplomatic relations internationally, it is assigned 25%; if Putin’s Russia had at least one recognized partner, 50%; and if Putin has established and maintained multiple partnerships with other nations, 75%.

[17] Foreign Assistance. U.S. Agency for International Development. Accessed May 20, 2024. https://www.foreignassistance.gov.

[18] “Russia and the World Bank: International Development Assistance.” The World Bank. Accessed May 20, 2024. https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/russia/brief/international-development#:~:text=The%20current%20cooperation%20between%20the,security%2C%20and%20global%20health%20–%20thereby.

[19] To subjectively determine if foreign aid would increase the regime’s ability to provide for human security functions, the following criteria were applied: If human insecurity appears endemic, foreign aid will likely not provide long-term security (25%). If aid reinforces sound governance structures that are temporarily at risk, it is assessed at 50%. If the regime receives little aid due to the strength of endogenous resources, the assessment is 75%.

[20] Cullen Hendrix, “Russia’s Boom Business Goes Bust,” Foreign Policy, May 30, 2023.

[21] To subjectively determine if security sector assistance would increase the regime’s ability to provide for national security functions, the following factors were considered: If military insecurity appears endemic, the success rate is assigned 25%. If military aid reinforces somewhat reliable security forces that require temporary external support, it is assessed at 50%. If the regime is self-reliant in meeting its security needs, the success rate is assigned 75%.

[22]Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, accessed May 21, 2024, https://carnegieendowment.org/.

[23] Global Terrorism Database, accessed April 3, 2024, https://www.start.umd.edu/gtd/.

[24] Katherine Bucker, “On the Terrorist Attack at the Crocus City Hall in Moscow,” U.S. Department of State, April 11, 2024, accessed May 21, 2024, https://osce.usmission.gov/on-the-terrorist-attack-at-the-crocus-city-hall-in-moscow/.

[25] The Global Economy, accessed May 21, 2024, https://www.theglobaleconomy.com/.

[26] Vision of Humanity, Global Peace Index, accessed May 21, 2024, https://www.visionofhumanity.org/maps/#/.

[27] Freedom House, accessed May 21, 2024, https://freedomhouse.org/.

[28] In subjectively assessing the population’s access to food as a measure of resistance, the following assumptions were made: If the country is on the CIA food insecurity list, the assessment is 75%, as food insecurity exists. If not, the measure is 25%, as the potential for food insecurity remains.

[29] Robert S. Burrell and John Collision, “A Guide for Measuring Resiliency and Resistance,” Illustration by Authors.

[30] The White House, National Security Strategy, October 2022.

[31] For determining support to resistance as a foreseeable policy option, the following considerations were applied: If the regime is a strategic rival of a strong competitor, the probability is 100%. If the regime faces strong opposition from rivals, 75%. If the regime is not on good terms diplomatically with other states but is not a declared rival, 50%. If the regime maintains good terms with most states, 25%. If the regime is an ally of the United States, the assessment is 0%.

[32] For additional information on this methodology, see Chris Mason, “Measuring and Quantifying State Fragility: Why Governments Lose Internal Conflicts and What That Means for Counterinsurgency,” in Resilience and Resistance: Interdisciplinary Lessons in Competition, Deterrence, and Irregular Warfare, ed. Robert S. Burrell (Tampa, FL: Joint Special Operations University Press, 2024).

[33] Vadim Volos, “Russian Opinion Poll in Wartime,” National Opinion Research Center, University of Chicago, November 2023, accessed May 21, 2024, https://www.norc.org/research/projects/russian-public-opinion-wartime.html#:~:text=Additionally%2, accessed on 21 May 2024.

[34] “Do You Approve of the Activities of Vladimir Putin as the President (Prime Minister) of Russia?” Statista.

[35] “Do You Approve or Disapprove of Alexey Navalny’s Activity?,” Statista, March 2, 2022, accessed May 31, 2024, https://www.statista.com/statistics/1109765/attitude-toward-activity-of-alexei-navalny-russia/.

[36] Erica Chenoweth and Christopher Wiley Shay, “List of Campaigns in NAVCO 1.3,” Harvard Dataverse, 2020, accessed May 22, 2024, https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataverse/navco.

[37] Harvard Dataverse, Mass Mobilization Protest Data, accessed May 22, 2024, https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataverse/MMdata; The Times (London), “Foreign Ways,” October 18, 2005.

[38] Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, Global Protest Tracker, accessed May 22, 2024, https://carnegieendowment.org/features/global-protest-tracker?lang=en.

[39] Nonviolent and Violent Campaigns and Outcomes (NAVCO).

[40] Tom Parfitt, “He Is Not Our Tsar, Anti-Putin Protesters Tell Russia,” The Times, May 7, 2018, 30.

[41] Nonviolent and Violent Campaigns and Outcomes (NAVCO).

[42] Nonviolent and Violent Campaigns and Outcomes (NAVCO).

[43] Total numbers include 22,000 protestors against constitutional reforms in February 2022 and 100,000 protestors following the arrest of Aleksei Navalny in January 2021. See Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, Global Protest Tracker, accessed June 24, 2024, https://carnegieendowment.org/features/global-protest-tracker?lang=en.

[44] Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, Global Protest Tracker, accessed May 22, 2024, https://carnegieendowment.org/features/global-protest-tracker?lang=en.

[45] “Yabloko Congress Elects Leaders and Calls for Ceasefire,” Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe, December 12, 2023, accessed May 23, 2024, https://www.aldeparty.eu/yabloko_congress_elects_leaders_and_calls_for_ceasefire.

[46] “Russia Dissolves Oldest Opposition Party,” The Moscow Times, May 25, 2023, accessed May 23, 2024, https://www.themoscowtimes.com/2023/05/25/russia-dissolves-oldest-opposition-party-a81282.

[47] Pjotr Sauer, “Putin Had Navalny Killed to Thwart Prisoner Swap, Allies Claim,” The Guardian, February 26, 2024, accessed May 23, 2024, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2024/feb/26/vladimir-putin-had-alexei-navalny-killed-to-thwart-prisoner-swap-allies-claim.

[48] Harvard Dataverse, Mass Mobilization Protest Data, accessed May 22, 2024, https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataverse/MMdata; The Times (London), “Foreign Ways,” October 18, 2005.

[49] In 2021, communist candidate Mikhail Sergeyevich Lobanov lost an election in the Kuntsevo Constituency of Moscow to a United Russia candidate, Yevgeny Popov. Lobanov subsequently claimed election fraud.

[50] Robyn Dixon, “Russia’s Rising Young Communists Pose an Unexpected New Threat to Putin’s Grip,” The Washington Post, October 6, 2021.

[51] “Russian Activist Missing In Georgia May Be In Russian Custody,” Radio Free Europe, November 8, 2023, accessed May 22, 2024, https://www.rferl.org/a/russia-georgia-artpodgotovka-missing/32676325.html.

[52] “Greenpeace Challenges Gazprom: Prevents Oil Production at Prirazlomnaya Field, 2012,” Global Nonviolent Action Database, Swarthmore College, accessed May 22, 2024, https://nvdatabase.swarthmore.edu.

[53] Uppsala Conflict Data Program, Uppsala University, accessed May 24, 2024, https://ucdp.uu.se/exploratory.

[54] Ibid.

[55] Jason Burke, “Who Is Thought to Be Behind the Moscow Attack?,” The Guardian, March 23, 2024.

[56] Kevin Shalvey, “Russian Rebellion Timeline: How the Wagner Uprising Against Putin Unfolded and Where Prigozhin Is Now,” ABC News, July 10, 2023, accessed May 22, 2024, https://abcnews.go.com/International/wagner-groups-rebellion-putin-unfolded/story?id=100373557.

[57] Alisa Zemlyanskaya, “This Train Is on Fire: How Russian Partisans Set Fire to Military Registration and Enlistment Offices and Derail Trains,” Europe Solidaire Sans Frontières, July 6, 2022, accessed May 23, 2024, https://web.archive.org/web/20220810092620/https://theinsider.pro/politika/252389.

[58] Jack Dutton, “Russian Anti-War Group Claims Responsibility for Train Crashes,” Newsweek, October 26, 2022, accessed May 23, 2024, https://www.newsweek.com/russian-anti-war-group-claims-behind-explosions-stop-wagons-1754898.

[59] Isabel van Brugen, “What Is ‘Black Bridge’? Anti-Putin Group Claiming FSB Building Fire,” Newsweek, March 21, 2023, accessed May 23, 2023, https://www.newsweek.com/black-bridge-russia-fsb-building-fire-rostov-don-1789215.

[60] Kyiv Post, “’Irpin Declaration’ on the Cooperation of the Russian Opposition Against Putin’s Regime,” September 1, 2022, accessed May 23, 2024, https://www.kyivpost.com/post/5321. David Axe, “Pro-Ukraine Russian Fighters Are Marching Deeper Into Russia but Taking Territory Isn’t the Goal: The Goal Is to Embarrass Vladimir Putin,” Forbes, March 17, 2024. Anna Kruglova, “The National Republican Army: A Potential Force of Resistance in Russia?,” RUSI, May 2, 2023, accessed May 22, 2024, https://rusi.org/explore-our-research/publications/commentary/national-republican-army-potential-force-resistance-russia. Jim Geraghty, “How Russians Are Joining the Fight Against Putin,” The Washington Post, March 22, 2024, accessed May 22, 2024, https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/2024/03/22/freedom-russia-legion-ilya-ponomarev-putin-ukraine/.

[61] Katja Lindskov Jacobsen and Karen Philippa Larsen, “Wagner Group Flows: A Two‐Fold Challenge to Liberal Intervention and Liberal Order,” Politics and Governance 12 (2024).

[62] “Russian Imperial Movement,” Mapping Militants Project, last updated 2023, accessed June 26, 2024, https://mappingmilitants.org/profiles/russian-imperial-movement#narrative. Michael R. Pompeo, “United States Designates Russian Imperial Movement and Leaders as Global Terrorists,” U.S. Department of State Press Release, April 7, 2024. Anna Kruglova, “For God, for Tsar and for the Nation: Authenticity in the Russian Imperial Movement’s Propaganda,” Studies in Conflict & Terrorism 47, no. 6 (October 19, 2021): 645–667.

[63] Federico Varese, et al. “The Resilience of the Russian Mafia: An Empirical Study.” British Journal of Criminology, vol. 61, no. 1, 2021, 143–166.

[64] Ben Makuch, “Russian Assassinations a Growing Worry as War Nears Second Year,” Vice News, February 9, 2023, accessed June 26, 2024, https://www.vice.com/en/article/v7vwa9/russia-assassinations-putin-ukraine-war.

[65] The figure illustrates significant Mexican resistance movements across a resistance continuum. The prominent nonviolent legal groups include political opposition parties: (1) Movimiento Ciudadano, (2) Partido Acción Nacional, and (3) Partido Revolucionario Institucional. Nonviolent illegal movements include (4) a well-organized women’s activist underground. Although violent rebellions (short-duration interruptions) are not currently apparent, insurgent groups include: (5) Cártel de Jalisco Nueva Generación, (6) Beltrán Leyva, (7) Cártel del Noreste and Los Zetas, (8) Guerreros Unidos, (9) Cártel del Golfo, (10) Cártel de Juárez, (11) La Línea, (12) La Familia Michoacána, (13) Los Rojos, and (14) Cártel de Sinaloa.