Introduction

On October 7, 2023, Hamas triggered a war with Israel by carrying out the deadliest terrorist attack per capita, massacring 1,200 innocent people—of whom at least 809 were civilians— and taking at least 251 hostages. [i] While Israel’s history has always been intertwined with the fight against terrorism, the unprecedented scale of the October 7 attack compelled Israeli leaders to launch an intensive aerial and ground campaign in the Gaza Strip, with the stated objectives of destroying Hamas, rescuing the hostages, and ensuring that Israel would no longer face existential threats from Gaza.[ii]

CONTACT Nelly Hernández Valdez | nh432@georgetown.edu

The views expressed in this publication are entirely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views, policy, or position of Georgetown University. © 2025 Arizona Board of Regents / Arizona State University

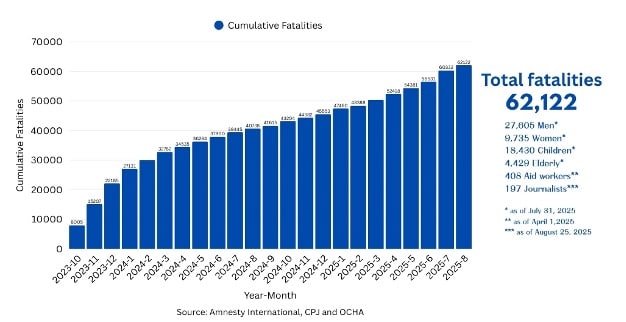

In response, the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) have conducted a retaliatory invasion of Gaza involving approximately 40,000 combat troops, dropped at least 70,000 tons of explosives—exceeding the combined weight of bombs dropped on London, Dresden, and Hamburg during all of World War II—[iii]displaced around 90 percent of Gaza’s population, and killed over 60,000 people.[iv] As a result, Israel’s counterterrorism campaign has itself become one of the deadliest for a civilian population per capita, both in terms of speed and scale. As the conflict has escalated beyond its initial objectives, it becomes necessary to critically assess not only the military outcomes but also the broader ethical and strategic implications of Israel’s counterterrorism campaign.

With the collapse of the January 2025 ceasefire and the intensification of violence against civilians, an essential question arises: whether the same degree of kinetic power that has effectively destroyed Gaza’s infrastructure and weakened Hamas militarily has also succeeded in dismantling the ideology that sustains the terrorist group. This research seeks to answer the following question: To what extent has Israel’s counterterrorism campaign against Hamas been effective, and to what extent has it adhered to the moral and legal standards of just war theory and mass atrocity prevention?

This research is structured into six analytical sections. The first section provides a background on Hamas. The second examines Israel’s counterterrorism doctrine, with particular focus on the principles and implications of the Dahiya Doctrine. The third analyzes the specific strategies and tactics employed by Israel since the October 7 attacks. The fourth section applies just war theory to assess the ethical dimensions of Israel’s response and identify key shortcomings in its adherence to its principles. The fifth section evaluates the ongoing war in Gaza through the lens of mass atrocity prevention, guided by Scott Straus’s analytical framework. The final section explores alternative strategies and tactics that were not pursued but could have offered more effective or ethically grounded outcomes.

Background

The Birth of Hamas

Harakat al-Muqawama al-Islamiya, better known as Hamas, was founded in December 1987 during the outbreak of the First Intifada, a Palestinian uprising against Israeli occupation. Although ideologically rooted in the Muslim Brotherhood, Hamas’s immediate emergence was triggered by a specific event: a traffic accident in Gaza involving an Israeli truck that killed several Palestinian workers and sparked riots.[v] Within days, the unrest evolved into a sustained uprising. On December 14, 1987, the Muslim Brotherhood issued a leaflet calling for resistance, marking the official birth of Hamas. Sheikh Ahmed Yassin, a cleric and longtime member of the Brotherhood, is credited as the group’s founder.[vi] He positioned Hamas as the Brotherhood’s political arm in Gaza, aiming to reassert Islamist leadership in the Palestinian resistance against Israel.[vii]

The Genocidal Spirit of Hamas

Hamas’s raison d’être is the elimination of the State of Israel. Rooted in a genocidal ideology, the group seeks the complete “liberation” of Palestine—from the Jordan River to the Mediterranean Sea—and the establishment of an Islamic state through armed jihad.[viii] To pursue this aim, Hamas employs a threefold strategy: providing social services to build popular support, participating in politics to challenge the authority of the secular Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) and Palestinian Authority (PA), and conducting guerrilla operations and terrorist attacks against Israeli soldiers and civilians.[ix]

Hamas’s categorical rejection of Jews and of peaceful resolution is explicit in its original 1988 Covenant, which declares: “The stones and trees will say: O Muslims, O Abdullah, there is a Jew behind me, come and kill him.”[x] The document also dismisses diplomacy outright, insisting that “initiatives, proposals, and international conferences are all a waste of time and vain endeavors.”[xi]Although Hamas issued a revised charter in 2017 that softened some of its overtly antisemitic language—claiming opposition to Zionism rather than Judaism—it continued to deny Israel’s right to exist and reaffirmed its goal of establishing an Islamist Palestinian state across present-day Israel, the West Bank, and Gaza, while fully endorsing the “right of return” for all Palestinian refugees.[xii]

Governing Gaza

Hamas’s rise to power was shaped by both popular support and the vacuum left by Israel’s 2005 withdrawal from the Gaza Strip. Although Israel’s military campaign had weakened Hamas operationally, its refusal to bolster the PA under Mahmoud Abbas alienated Palestinian moderates.[xiii] In the 2006 elections, Hamas won a legislative majority, capitalizing on its reputation for social services and rejection of corruption associated with Fatah.[xiv] Tensions between Fatah and Hamas culminated in a violent split in 2007. Hamas seized full control of Gaza after routing Fatah forces, establishing itself as the de facto authority. It then created parallel institutions, including a judiciary and internal security apparatus, often ruling with authoritarian methods. Elections have not been held in Gaza for the legislature since 2006, nor for president since 2008.[xv]Leaders and Funding

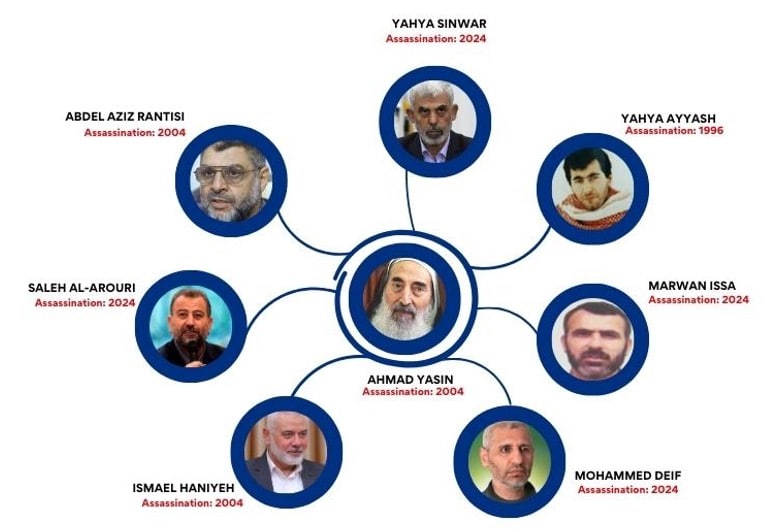

Claims that Hamas maintains distinct political and military wings are deeply misleading. From its inception, the organization has operated as a unified structure. Its founder, Ahmed Yassin, played both spiritual and operational roles. As he famously stated, “We cannot separate the wing from the body. If we do so, the body will not be able to fly.”[xvi] Successive leaders such as Abdel Aziz al-Rantissi and Yahya Sinwar have similarly embodied this duality. Sinwar, for example, formerly led Hamas’s military wing before assuming political leadership and was a principal architect of the October 7, 2023, attacks prior to being killed in an Israeli airstrike.[xvii]

Hamas’s financial infrastructure is both transnational and opaque. The group sustains itself through a complex web of state sponsorship, diaspora contributions, and the misuse of charitable organizations. Iran alone is estimated to contribute up to $100 million annually to Hamas and other Palestinian militant groups.[xviii] Turkey and Qatar have also provided political support and financial assistance, with Hamas’s political bureau based in Doha. Domestically, Hamas capitalizes on the “dawa”—its social welfare network—which serves not only as a tool for grassroots legitimacy but also as a covert logistical platform for financing terrorism. As Levitt notes, “The dawa serves as the ideal logistical infrastructure for a terrorist network—blurring the lines between charity and terror.” The dual-use nature of these institutions makes counterterrorism efforts particularly complex and challenging.

The October 7 Attacks

“Kill as many people and take as many hostages as possible” were the instructions reportedly given to Hamas fighters ahead of the October 7, 2023 attacks.[xix] On that day, Hamas launched a surprise, coordinated assault on southern Israel by land, sea, and air—executed primarily by over 1,000 members of the Izz ad-Din al-Qassam Brigades.[xx] The operation caused approximately 1,200 fatalities—including at least 809 civilians and 314 Israeli military personnel—and the abduction of at least 251 hostages.[xxi] Hamas employed swarming tactics designed to breach Israel’s border defenses, paralyze command and control systems, overwhelm first responders, and sow widespread confusion.[xxii]

The attack inflicted unprecedented casualties: more than 14,900 people were wounded and required hospitalization.[xxiii] One-third of the victims were massacred at the Nova music festival.[xxiv] Other atrocities included the killing of unarmed and untrained female intelligence observation soldiers, and in one reported case, a nine-month-old infant hiding with her mother.[xxv] Many experts argue that, beyond inflicting mass casualties, Hamas’s intent was to provoke a large-scale Israeli military response and escalate the conflict.[xxvi]

Israel’s Counterterrorism Approach: The Dahiya Doctrine

A persistent weakness of Israel’s counterterrorism policy is the disconnection between its tactical military responses and a broader, coherent strategic vision. As Byman argues, Israel has long prioritized operational effectiveness and immediate deterrence over long-term political outcomes, often displaying “a focus on the present to the exclusion of future problems.”[xxvii] This short-term orientation is especially evident in Israel’s application of the Dahiya Doctrine, a counterterrorism approach that emphasizes the use of overwhelming and disproportionate force in response to attacks by non-state actors.

The Dahiya Doctrine takes its name from the Dahiya neighborhood in Beirut, which was devastated by Israeli bombardment during the 2006 Lebanon War. Then-General Gadi Eisenkot, who later served as IDF Chief of General Staff, articulated the core logic behind the doctrine in 2008:

What happened in the Dahiya quarter of Beirut in 2006 will happen in every village from which Israel is fired on […] We will apply disproportionate force and cause great damage and destruction there. From our standpoint, these are not civilian villages, they are military bases. This is not a recommendation. This is a plan. And it has been approved. [xxviii]

Promoted by Israeli military thinkers such as Col. Gabi Siboni, the doctrine explicitly embraces disproportionate force not just to neutralize enemy combatants but to deter future hostilities by imposing massive punishment.[xxix] This approach, however, is incompatible with international humanitarian law, which requires proportionality and the protection of civilians in armed conflict.[xxx] Despite these legal and ethical concerns, the doctrine has continued to shape Israel’s operations in Gaza, notably during Operation Cast Lead (2008–2009), Operation Protective Edge (2014), and the current Swords of Iron War launched in response to the October 7 attacks.[xxxi]

While the Dahiya Doctrine may align with one of the stated objectives of the Swords of Iron War—the destruction of Hamas’s military capabilities—it is arguably ill-suited to advancing two other key goals: the rescue of hostages and the long-term prevention of existential threats from Gaza. The use of overwhelming and indiscriminate force not only endangers the lives of hostages held in densely populated civilian areas, but also fails to prevent future violence. Despite having been implemented in previous conflicts, the doctrine did not deter Hamas from launching the October 7, 2023, attacks—the deadliest terrorist assault in Israeli history, underscoring its strategic limitations.

Moreover, key provisions of the Dahiya Doctrine, as formulated by Col. Gabi Siboni and General Eisenkot, appear to have been ignored. Among them are the recommendations to “reduce the period of fighting to a minimum,” to “create an effective balance of deterrence,” and to ensure that “the primary goal must nonetheless be to attain a ceasefire under conditions that will increase Israel’s long-term deterrence and prevent a war of attrition.”[xxxii] Instead, the campaign has become prolonged and increasingly disconnected from its original objectives.

Notably, Gen. Eisenkot, who returned as a key adviser to Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s war cabinet in October, resigned in June 2024, citing a lack of political will to end the war. In his words, “there are people sitting in the room who do not want to see the war end.”[xxxiii] He further criticized the government’s contradictory approach, pointing out that while Netanyahu claimed there would be no military occupation or new settlements, documents suggested otherwise.[xxxiv] Eisenkot’s resignation highlights how political ambitions have overridden some of the doctrine’s own strategic logic.

The modification in Israel’s objectives became more evident following the collapse of the 42-day ceasefire that began in January 2025. On March 30, Netanyahu laid out an updated plan that, beyond disarming Hamas, explicitly promoted the Trump plan for permanently displacing Palestinians from Gaza, stating: “We will see to the general security in the Gaza Strip and will allow the realization of the Trump plan for voluntary migration.”[xxxv] As Eisenkot cautioned, Israel is now actively fragmenting Gaza—maintaining troops inside the territory and gradually taking control of key areas, including Rafah, the critical border crossing with Egypt.[xxxvi] By doing so, Israel is effectively ensuring that the only access into and out of Gaza is through its territory. The endorsement of forced displacement and the construction of what President Donald Trump called “the Riviera of the Middle East”[xxxvii] points to a broader strategy aimed not only at restructuring Gaza’s political and security apparatus but also at transforming its geography and even its population.

Although some aspects of the Dahiya Doctrine—such as limiting the duration of conflict and pursuing a ceasefire under terms that strengthen deterrence—have been disregarded, its core principle of large-scale punishment and the destruction of entire urban areas has laid the groundwork for Israel’s broader strategy. By destroying Gaza’s infrastructure, the doctrine effectively eliminates the conditions necessary for Palestinians to sustain life in the territory, thus facilitating the promotion of so-called “voluntary migration.” This same destruction also creates the pretext for a new phase of “development,” aligned with the Trump plan, while enabling Israel to reshape Gaza’s security, political, geographic, and even demographic architecture to match its vague long-term ambitions.

However, the doctrine fails to address the key drivers of terrorism: political grievances, perceived injustice, and ideology. Without confronting the underlying political and ideological forces that sustain groups like Hamas, Israel’s decisions risk feeding a cycle of violence and ensuring long-term insecurity. Moreover, Israel is a liberal democracy that subscribes to the just war theory, the Dahiya Doctrine, even with the initial stated objectives, is contradictory to its principles, which will be examined later in the Mass Atrocity Lens discussion.

Strategies and Tactics

Strategic Incoherence and the Limits of Military Powers

Under Prime Minister Netanyahu, Israel’s war in Gaza appears to lack a coherent strategy. As strategist Colin Gray has noted, strategy is neither policy nor combat—it is the essential bridge between them.[xxxviii] If war is indeed the continuation of politics by other means, then it must be capable of producing political outcomes through military action. This is precisely where Israel’s campaign falters: it lacks a clear and unified plan that connects its military operations to achievable political ends.

The three central goals for the war are clear: the destruction of Hamas, the rescue of the hostages, and the elimination of future existential threats from Gaza. However, military force divorced from political context is strategically meaningless. In this vacuum, the objective of eradicating Hamas has been interpreted primarily as the physical destruction of the group—not as an effort to dismantle its ideology or appeal, but “its removal as a quasi-state able to threaten Israel’s borders.”[xxxix] While the physical elimination of a terrorist organization may be technically achievable, it directly conflicts with the parallel goal of rescuing hostages, who are being used by Hamas as human shields.[xl]

This contradiction exposes a deeper weakness in Israel’s approach: its overreliance on military means. For instance, Israel has justified the break of the ceasefire by claiming that doing so would accelerate the release of hostages. Yet, in practice, it has been negotiation—not force—that has secured the freedom of most hostages taken during the October 2023 attacks.[xli] Without a political track to complement its military campaign, Israel’s strategy risks collapsing under the weight of its own contradictions.

Another major gap in Israel’s strategy is the absence of a credible “day after” plan for Gaza. In his address to the U.S. Congress, Netanyahu stated that the future of Gaza should be both demilitarized and deradicalized.[xlii] However, the means by which Israel is attempting to demilitarize Gaza—through widespread destruction—undermine the goal of deradicalization. Military experts have warned that the scale of devastation and the deep grievances it generates are likely to fuel further radicalization, potentially producing new Hamas recruits or even more extreme actors. As former U.S. Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin cautioned: “In this kind of fight, the center of gravity is the civilian population. And if you drive them into the arms of the enemy, you replace a tactical victory with a strategic defeat.”[xliii]

Tactics

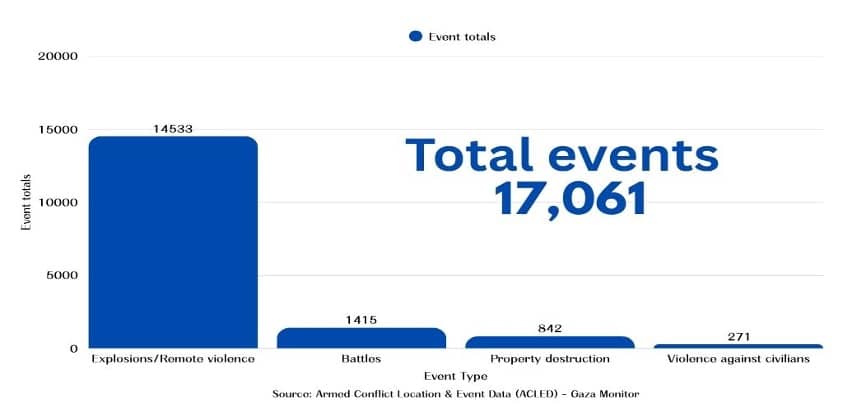

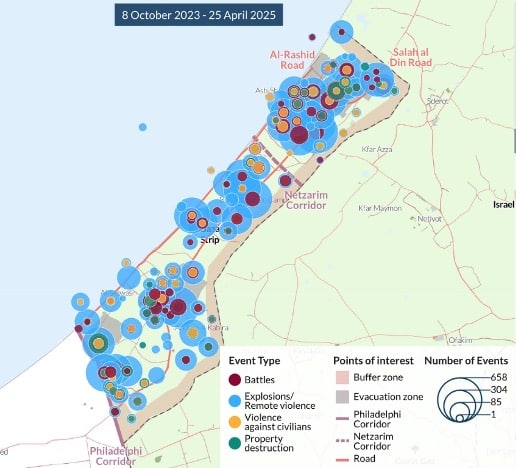

Despite the absence of a comprehensive strategy, the IDF, following the Dahiya Doctrine, has focused on large-scale aerial bombardments, ground invasion, siege tactics, urban and underground warfare, and the systematic destruction of civilian infrastructure suspected of serving as cover for Hamas operations. These tactics have been particularly successful in physically destroying Hamas leadership and reducing its military manpower.

Hamas Composition

The IDF has had tactical success in eliminating key Hamas leaders, including Yahya Sinwar, military chief Mohammed Deif, and Deif’s deputy, Marwan Issa.[xliv] Before the war, Hamas’s fighting force was estimated at 25,000 to 30,000 members.[xlv] According to Israeli claims, approximately 17,000 militants have been killed, and most of the group’s 24 battalions have been dismantled.[xlvi] However, data from ACLED, based on detailed IDF reports that include the timing, location, and nature of operations, suggest a lower figure—approximately 8,500 militant fatalities as of October 6, 2024, one year after the war began.[xlvii]

While targeting Hamas’s leadership may hold tactical and symbolic value, its strategic impact must be evaluated in light of the organization’s specific characteristics. As Byman explains, targeting key figures like bomb makers, trainers, or recruiters can be effective because those roles require years of experience and are hard to replace.[xlviii] In those cases, even if a group still has recruitment capacity, it may no longer be able to operate effectively. Nonetheless, Hamas does not have a profile to be defeated solely on this basis. Eliminating a terrorist organization by a decapitation strategy works best against small, centralized groups with one main leader and a short history.[xlix] In contrast, Hamas has operated for over 40 years, is deeply networked, and benefits from state support. If Hamas were vulnerable to this strategy, it would likely have ceased to function long ago.[l]

Figure 1. Hamas Leaders Eliminated by Israel Hostages

Israel has succeeded in securing the release of nearly 60 percent of the hostages, reducing the total number from 251 to 59, of whom only 24 are believed to be alive.[li] Around 150 were released through ceasefire agreements, while military operations have rescued just eight.[lii] Despite this, the new and more aggressive IDF chief of staff, Lt. Gen. Eyal Zamir, is pushing for renewed large-scale operations in Gaza—sparking concern among the Israeli public and hostage families, who favor negotiations over continued fighting.[liii] Former hostages have testified that Israeli strikes made their conditions worse and left them fearing death from either their captors or the bombardments.[liv]

Hamas Infrastructure

The IDF has also faced an especially complex challenge in Hamas’s vast and sophisticated tunnel system beneath Gaza. Often referred to as the “Gaza Metro,” this system has been under construction since 2007 and consists of 350 to 450 miles of subterranean infrastructure used for movement, weapons storage, ambushes, and command-and-control.[lv] Despite sustained efforts during the current war, the IDF has only destroyed around a quarter of these tunnels.[lvi] However, urban warfare experts argue that eliminating Hamas’s operational capabilities does not require destroying the entire network.[lvii] Strategically, Israel is prioritizing high-value targets—such as cross-border tunnels or those used for command and logistics—rather than attempting full eradication, which would demand years and a scale of resources that exceeds Israel’s current capabilities.[lviii]

Before October 2023, the IDF’s approach to tunnel warfare was based on the principle that only specially trained units should engage with subterranean threats, while regular troops were sent underground only as a last resort—an approach that contrasts with U.S. military doctrine, which generally advises avoiding tunnel environments altogether whenever possible.[lix] This mindset has shifted dramatically, based on trial-and-error approaches, from unsuccessful attempts to flood tunnels to dangerous incursions resulting in casualties.[lx] Today, the IDF has developed a new doctrine, combining surface and subsurface operations in dense urban environments.[lxi] Some IDF units now use Hamas’s tunnels as corridors for offensive maneuvers—a first in modern urban warfare.[lxii] This transformation—from avoidance to integration—marks a paradigm shift that could shape how future militaries approach underground warfare.

Figure 2. Total Number of Events by Type Conducted by Israeli Forces in Gaza as of April 2025.

Figure 3. Distribution of Events Conducted by Israeli Forces in Gaza as of April 2025 (Source: ACLED – Gaza Monitor)

Counterterrorism and Just War Theory

Just War Theory is grounded in the idea that while there may be morally acceptable reasons to resort to war, the conduct of war must still abide by ethical constraints. One of its most prominent thinkers, Walzer, argues that terrorism is inherently unjust because it intentionally targets civilians: “Its purpose is to destroy the morale of a nation, or class, to undercut its solidarity; its method is the random killing of innocent people.”[lxiii] While Hamas defends its actions by invoking the language of anti-colonial resistance—echoing thinkers like Jean-Paul Sartre, who once wrote that killing an oppressor is an act of self-liberation—[lxiv]Walzer challenges this logic. He warns that such reasoning can lead to moral nihilism, in which all members of the opposing society become legitimate targets.[lxv]

Just War Theory consists of three core principles: jus ad bellum (the justice of going to war), jus in bello (justice in how war is conducted), and jus post bellum (justice in the aftermath).[lxvi] Each principle provides a lens to evaluate a conflict’s legitimacy and morality. Jus ad bellum asks: Was the war justified? Jus in bello: Were the methods used in war ethical? And jus post bellum: Was the war’s aftermath handled justly? For Luban, the cornerstone of a just war is the existence of a just cause—“the paradigmatic example being self-defense.”[lxvii] In the case of Israel, following the deadliest terrorist attack in its history, the justification for war as an act of self-defense is clear. However, the conduct of that war, particularly under the Dahiya Doctrine, raises serious concerns under the jus in bello framework. As Walzer cautions, “It is perfectly possible for a just war to be fought unjustly.”[lxviii]

Jus ad Bellum

A war may be considered just not only when it is fought in self-defense, but also when it is waged with the right intention. In Israel’s case, the initial justification meets this threshold: Hamas has repeatedly targeted civilians with terrorist attacks since its founding, and the October 7, 2023, massacre left little doubt about the need for a forceful response. However, right intention becomes more questionable as Israel’s war objectives shift. The promotion of a “voluntary migration” plan for Gaza raises concerns about whether the aim is to make life unlivable for the 2.1 million civilians in the Strip—a tactic that could amount to ethnic cleansing.[lxix] In other words, right intention means no revenge, but Netanyahu’s actions often seem guided by revenge, “perhaps to make up for his actual responsibilities for what happened.”[lxx]

Jus in Bello

One of the most consistent critiques from human rights organizations and international legal bodies is that the Israeli leaders’ treatment of Gaza’s civilian population amounts to war crimes and crimes against humanity.[lxxi] As of now, Israeli operations have killed over 62,122 Palestinians and injured more than 156,758.[lxxii] Israel’s general stance toward civilians has often appeared hostile—something reflected in the statement of its UN representative, who declared: “While the hostages were guarded by terrorists, Gazan civilians were their jailors,” adding that these “so-called innocent civilians” were complicit in Hamas’s crimes.[lxxiii]

Although Hamas fights unjustly—embedding itself within the civilian population and using them as shields—this does not exempt Israel from its legal and moral duty to distinguish between combatants and non-combatants. Hamas’s own disregard for civilian welfare is evident in its use of vast resources to build military infrastructure. According to the IDF, the value of just 30 discovered tunnels is estimated at $90 million—funds that could have been invested in public services for Gaza’s residents.[lxxiv] Yet even in the face of Hamas’s cynicism, Israel’s response must remain within ethical limits. Acting as though high levels of collateral damage imply fewer civilians joining insurgent groups ignores both historical lessons and legal boundaries. As terrorism achieves its strategic objectives not through the act itself, but through the reaction it provokes from states.[lxxv]

The principle of proportionality also prohibits the use of inherently immoral tactics, regardless of strategic utility. One such example is the use of starvation as a method of warfare, which constitutes a war crime under international law.[lxxvi] Around the Jabalia refugee camp, for instance, the UN attempted 165 humanitarian deliveries between October 6 and December 31, 2024. Of these, 149 were denied, and the remaining 16 faced serious impediments.[lxxvii] At the same time, Israel’s airstrikes have caused an unprecedented toll on aid workers: at least 408 have been killed in Gaza since October 7, 2023—including 280 UNRWA staff, 34 from the Palestinian Red Crescent,[lxxviii] and seven international employees from World Central Kitchen.[lxxix] The death toll has also impacted journalists. As of May 2, 2025, the Committee to Protect Journalists reported that at least 197 journalists and media workers have been killed in Gaza, the West Bank, Israel, and Lebanon since the war began, making it the deadliest period for the press since this organization began collecting such data in 1992.[lxxx]

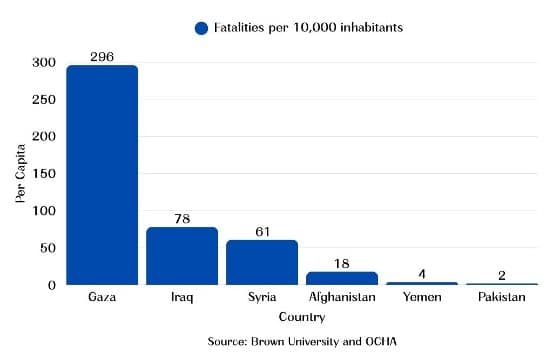

To date, Israel’s war against Hamas has become the deadliest counterterrorism campaign per capita in modern history. This reality raises serious questions about the ethical and legal conduct of the war when examined through the lens of jus in bello.

Figure 4. Total Fatalities Inflicted by Israeli Forces in Gaza

Figure 5. The Deadliest Counterterrorism Campaign Per Capita for Civilians

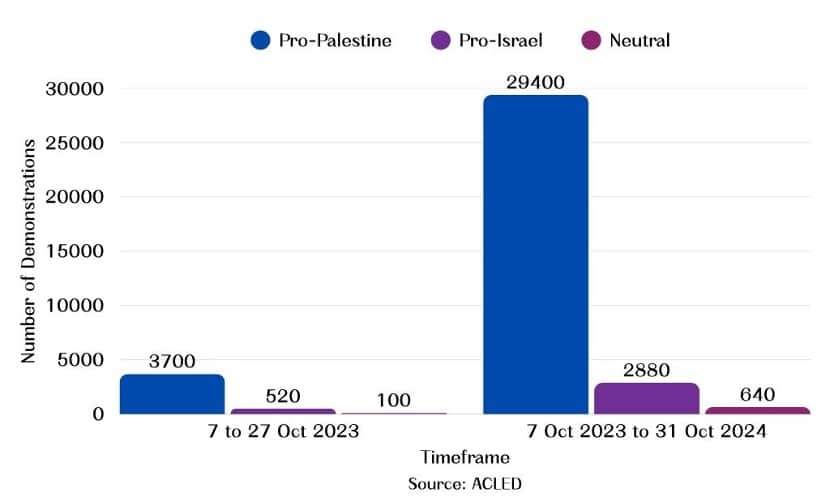

Figure 6. Total of Global Demonstrations in Response to the Israel-Gaza Conflict

Jus post bellum

Jus post bellum refers to the principles that should govern the transition from war to peace, including reconstruction, accountability, and fair treatment of those affected.[lxxxi] As Alexander and Norris explain, states involved in a conflict—and those that support them—bear particular responsibility toward civilian populations.[lxxxii] In this case, the United States, which provided 69% of Israel’s major arms imports between 2019 and 2023, holds a central role.[lxxxiii] According to National Security Memorandum 20, countries receiving U.S. defense articles must comply with international humanitarian law and must not obstruct humanitarian aid.[lxxxiv] By continuing to provide military support without clear conditions, the U.S. has not only enabled violations during the war but has also taken on a moral obligation to assist in rebuilding Gazan civil society. Yet, current narratives—such as turning Gaza into a “Riviera in the Middle East” without a clear plan for its people—suggest that such responsibility is being ignored.

Accountability remains highly uncertain. The International Criminal Court (ICC) issued arrest warrants for three senior Hamas figures—Ismail Haniyeh, Yahya Sinwar, and Mohammed Deif—but closed the cases following confirmation of their deaths.[lxxxv] It has also charged Israeli Prime Minister Netanyahu and former Defense Minister Yoav Gallant as co-perpetrators of war crimes and crimes against humanity, including the use of starvation as a method of warfare, deliberately targeting civilians, and committing acts of persecution and inhumane treatment.[lxxxvi] Yet despite these charges, Netanyahu has traveled freely to the United States without consequence, setting a troubling precedent that undermines the principle that no one is above the law. Although neither Israel nor the United States is a party to the Rome Statute, Gaza falls under ICC jurisdiction.[lxxxvii] Meanwhile, Israel’s stated focus remains the total destruction of Hamas, not the legal prosecution of its members. Taken together with its conduct under jus ad bellum and jus in bello, this reality casts serious doubt on the prospects for a just and lawful postwar resolution.

Mass Atrocity Lens

At the 2005 United Nations World Summit, member states committed to the “Responsibility to Protect” (R2P) populations from genocide, war crimes, ethnic cleansing, and crimes against humanity—collectively known as mass atrocities.[lxxxviii] R2P outlines a continuum of obligations for both states and the international community to prevent mass atrocities, to react when they occur, and to help rebuild in their aftermath. Among these, prevention is widely recognized as the most crucial responsibility.[lxxxix]

Scholars like Straus have identified key warning signs that often precede mass atrocities, such as political polarization, dehumanization of targeted groups, and militarization, often accompanied by laws enabling state-led violence.[xc] However, two conceptual problems hinder timely international responses. First, there is a widespread misconception that mass atrocities exist in a hierarchy, with genocide positioned as the “crime of crimes.”[xci] While genocide is indeed legally complex, mainly due to the difficulty of proving intent, this perceived hierarchy has led to the mislabeling of other atrocities as genocide to prompt more decisive international action. Second, genocide is too often understood exclusively through the lens of the Holocaust.[xcii] This framing not only renders other genocides less visible but also creates a false scale of severity and affects the understanding that genocide is not a singular event, but a process that unfolds over time.[xciii]

This broader understanding of mass atrocities is particularly relevant in the case of Gaza. In her report Anatomy of a Genocide, UN Special Rapporteur Francesca Albanese argues that genocide often begins with systematic dehumanization and the erosion of a group’s right to exist.[xciv] She finds reasonable grounds to believe that Israel is committing genocidal acts in Gaza—through the killing of group members, the infliction of serious bodily and mental harm, and the deliberate imposition of conditions of life calculated to destroy the group in whole or in part.[xcv] Similarly, the Report of the Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Occupied Palestinian Territory, including East Jerusalem, and Israel emphasizes that the October 7 attacks and Israel’s subsequent military campaign must be understood in the broader historical context of prolonged occupation, structural violence, and the denial of Palestinian self-determination.[xcvi] Recognizing these patterns not only underscores the urgent need for coordinated responses to all forms of mass atrocity—not just genocide—but also signals the dangers of disproportionate warfare as a potential pathway to genocidal violence.

Hamas’s genocidal intent is well documented in its founding charter. However, another key indicator of mass atrocity risk is the absence of moderating leadership on both sides of a conflict.[xcvii] This appears to be the case in Israel, where far-right extremists have gained substantial influence. As U.S. Senator Jack Reed noted, “Netanyahu has made common cause with far-right extremists who pursue their own agendas at the expense of Israel’s security and have encouraged his most misguided policies.”[xcviii] Genocidal rhetoric from Israeli leaders has further escalated tensions. Prime Minister Netanyahu referred to Palestinians as “Amalek,” while the former Defense Minister called them “human animals”—language disturbingly reminiscent of the dehumanization seen in the Rwandan genocide.[xcix] President Isaac Herzog claimed that “an entire nation is responsible” for the October 7 attacks, and other officials have openly advocated for the destruction of Gaza, including the use of nuclear force.[c] If Israel claims to seek the deradicalization of Gaza, it must begin by deradicalizing its own political discourse and actions.[ci]

Evaluating Overlooked Tactics and Their Potential Impact

From Body Counts to Ideological Defeat: The Missing Political Strategy

Israel’s counterterrorism strategy in Gaza has prioritized the number of Hamas fighters killed as a measure of success—an approach both misleading and ineffective. Military force is sometimes necessary, especially against core leaders, but as one IDF official remarked, it should be M-16s, not F-16s.[cii] Excessive reliance on airstrikes and mass casualty operations fuels further radicalization and alienates the very populations whose disengagement from Hamas is critical to long-term security.

A more effective strategy would focus on eroding Hamas’s support base by empowering political alternatives and demonstrating that Gazans have viable, moderate leadership options. Historical evidence supports this approach. Kurth Cronin’s analysis of 457 terrorist groups over the past century shows that groups like Hamas end by collapsing internally or losing public support.[ciii] Before the October 7 attacks, Hamas had already lost much legitimacy among Palestinians—its approval ratings dropped from 62% in 2007 to just one-third by 2014.[civ] But Israel’s overwhelming military response reversed this trend, allowing Hamas to regain credibility as a defender of Palestinians.[cv]

Rather than isolate Hamas, Israel has at times strengthened it—undermining the Palestinian Authority in an effort to weaken the prospects of a two-state solution.[cvi] By facilitating Qatari funds to Hamas, Netanyahu’s government sidelined moderate actors like Abbas, ensuring internal Palestinian division and providing a pretext to avoid negotiations.[cvii] This short-term tactic proved disastrous, ultimately contributing to the conditions that enabled the October 7 attacks.

If Israel fails to change course, it risks further strategic losses—particularly with its most important ally. U.S. public support for Israel is in decline, especially among younger Americans, where favorability has fallen by 26 points—from 64% to 38%.[cviii] Meanwhile, the devastation in Gaza is not only hardening Palestinian attitudes but also forging new alliances among otherwise divided militant groups. Hamas, a Sunni group, is now close with Shiite actors like the Houthis and Hezbollah—groups that would otherwise be in conflict but are united by Israel’s actions in Gaza.[cix] Without a shift toward political engagement and restraint, Israel may continue to win tactical battles, but at the cost of long-term strategic defeat.

Elevating Diplomacy and Narrative Power in Israel’s Counterterrorism Approach

The fact that global outrage has centered more on Israel than on Hamas underscores Israel’s failure in the realm of public diplomacy and information warfare. In the immediate aftermath of the October 7 attacks, Israel demanded that countries publicly condemn Hamas. However, in diplomacy, form is substance. Rather than building strategic consensus, Israel’s confrontational tone alienated even its closest regional allies. Colombia, once Israel’s strongest partner in Latin America, became the third country in the hemisphere to sever diplomatic ties, citing Israel’s military offensive in Gaza as genocidal.[cx] Belize also severed ties, citing Israel’s “obstruction of humanitarian aid”, and Bolivia cited “crimes against humanity.”[cxi]

Instead of engaging these governments through dialogue, Israel responded by accusing them of aligning with Hamas and submitting to Iranian influence.[cxii] Mexico, which maintains a long-standing foreign policy rooted in principles such as non-intervention, self-determination, national sovereignty, legal equality among states, and the peaceful resolution of disputes, was also criticized. An Israeli statement claimed that Mexico’s neutral stance amounted to support for terrorism—[cxiii]even though Mexico explicitly condemned the October 7 attacks, during which two of its nationals were taken hostage.[cxiv]

These reactions reflect a misreading of regional political cultures and a failure to adapt public diplomacy efforts strategically. Rather than issuing demands, Israel should have focused on building trust through contextualized outreach and respect for national positions. The assumption that effective policy makes public diplomacy unnecessary is fundamentally flawed.[cxv] In Israel’s case, the absence of a coherent strategy—or worse, the implementation of counterproductive policies—undermined its diplomatic credibility.[cxvi]

Another central challenge in Israel’s counterterrorism approach has been its handling of the information environment. Israeli officials view themselves as targets of a broad campaign of disinformation and propaganda. As Dr. Omer Dostri, spokesperson for the Prime Minister, has claimed, even UN Secretary-General António Guterres has echoed narratives aligned with Israel’s adversaries, including those propagated by Hamas since October 7.[cxvii] While Hamas has leveraged digital platforms to legitimize its governance and demonize Israel–its primary targets are their domestic constituents–[cxviii] and Israel’s response has leaned heavily on content suppression rather than strategic engagement.

Instead of prioritizing transparency and proactive communication, Israeli authorities have increasingly turned to censorship to counter perceived information threats. On November 14, 2023, Israel’s Cyber Unit submitted more than 9,500 takedown requests to social media platforms—60 percent of which were directed to Meta.[cxix] An Israeli official reported that platforms complied with 94 percent of these requests.[cxx] Between October and November 2023, Human Rights Watch documented over 1,050 instances of content suppression on Instagram and Facebook, mainly targeting posts by Palestinians and their supporters that documented human rights violations.[cxxi]

This approach, however, risks being counterproductive. Censorship not only undermines democratic norms but also weakens Israel’s credibility in the international arena. The most effective way to counter disinformation is not through silencing dissent, but by consistently providing timely, accurate, and transparent information.[cxxii] In the digital age, where perception shapes legitimacy, public trust is earned through openness, not control.

Elevating Women and Strengthening Strategy: Application of the WPS Agenda

Since the October 7 attacks, the visibility of Israeli women in combat has increased significantly, with mixed-gender units and even all-female tank crews deployed to Gaza.[cxxiii] Yet, these operational shifts have not translated into structural commitments to integrate the Women, Peace, and Security Agenda (WPS) within Israel’s security apparatus. Israel remains one of the states without a National Action Plan (NAP) to implement United Nations Security Council Resolution 1325.[cxxiv] The resolution calls on states to integrate women into peace and security decision-making at all levels, to prevent conflict and address conflict-related sexual violence, to incorporate gender perspectives into planning, policies, and operations, and to ensure that women’s needs and voices are central during relief and recovery efforts.[cxxv]

Although Israel was the first UN member to incorporate elements of Resolution 1325 into national law, implementation has been minimal. The expansion of women’s roles within the IDF stands in sharp contrast to the current low point in women’s political representation in government, the most far-right in Israel’s history.[cxxvi] While the number of women in combat roles has increased, the war cabinet assembled after October 7—comprising two former chiefs of staff and a general—does not include any women.[cxxvii] The absence of a NAP underscores a contradiction between Israel’s tactical reliance on women in wartime and the absence of institutional mechanisms to ensure their meaningful participation in policymaking, raising questions about the normative legitimacy of its security commitments and the long-term effectiveness of its counterterrorism strategy.

UNSCR 2242 (2015) further calls for stronger integration between the WPS and counterterrorism/countering violent extremism (CT/CVE) agendas, including through mainstreaming gender perspectives and ensuring women’s participation and that of women’s organizations in shaping CT/CVE policies.[cxxviii] Yet Israel has missed a crucial opportunity to advance this agenda. Since the 2000s, civil society organizations such as Itach-Maaki and the Center for Women in the Public Sphere (WIPS) have consistently advocated for the adoption of a NAP, but their efforts have not been translated into policy.[cxxix]

Integrating the WPS agenda into the security apparatus is not only a matter of women’s rights but also a strategic imperative in counterterrorism. Civil society engagement and gender-inclusive approaches could have provided alternatives to Israel’s current overreliance on military solutions in Gaza. Studies consistently show that when women participate in peace processes, the likelihood of the agreement lasting at least two years increases by 20 percent, and the probability of lasting 15 years rises by 35 percent.[cxxx] Failing to capitalize on this evidence-based advantage reflects a missed opportunity to align operational necessity with long-term strategic sustainability.

Conclusion

This research has examined Israel’s counterterrorism campaign against Hamas through strategic, ethical, and normative lenses. Hamas’s founding ideology—rooted in jihadist violence and the goal of Israel’s destruction—has shaped its hybrid strategy of governance, armed struggle, and psychological warfare. The October 7 attacks marked the deadliest escalation in the conflict’s history and were designed not only to inflict mass casualties but also to provoke a sweeping Israeli military response.

In examining Israel’s counterterrorism doctrine, this paper highlighted the central role of the Dahiya Doctrine, which emphasizes overwhelming force as a deterrent. While such tactics have dealt significant damage to Hamas’s operational infrastructure, they have failed to achieve Israel’s broader strategic goals, such as rescuing hostages or preventing future radicalization. Instead, the disproportionate application of force has undermined Israel’s own ethical standards and contributed to long-term instability.

Strategically, the campaign suffers from incoherence. The lack of a credible “day after” plan for Gaza, the contradiction between military operations and hostage negotiations, and the absence of a political track all point to a disconnect between means and ends. Tactical gains—such as leader assassinations and tunnel destruction—cannot substitute for a political strategy that addresses the ideological roots of Hamas and provides a path toward de-escalation and governance reform.

When evaluated through the lens of Just War Theory, Israel’s campaign begins with a clear case for self-defense but quickly falters in its conduct. Violations of proportionality, harm to civilians, obstruction of humanitarian aid, and the use of starvation as a weapon raise serious questions about the moral and legal legitimacy of its operations. The same concerns apply to Israel’s responsibilities of jus post bellum, particularly its obligations to rebuild, ensure accountability, and respect civilian dignity.

Through the mass atrocity prevention lens, Israel’s actions exhibit troubling parallels with early warning signs of mass violence. The presence of dehumanizing rhetoric, targeting of civilian infrastructure, and consolidation of far-right leadership deepen concerns. While Hamas’s genocidal ideology is well-documented, Israel’s conduct does not meet its own democratic standards and risks fueling further cycles of radicalization.

More constructive alternatives were available. Rather than measuring success through body counts, Israel could have adopted a strategy centered on weakening Hamas’s support base by empowering moderate Palestinian actors. Evidence shows Hamas’s popularity was in decline before October 7. However, Israel’s actions have revived its legitimacy and eroded trust among international actors. Israel also missed critical opportunities to leverage diplomacy and public narrative. Confrontational diplomacy alienated some countries, while censorship undermined its credibility in the information space. A strategy rooted in transparency and context-sensitive engagement would have strengthened international support and legitimacy.

Finally, the increased visibility of women in the IDF could have been leveraged to strengthen Israel’s commitment to United Nations Security Council Resolutions 1325 and 2242 by advancing gender-inclusive leadership and policymaking. Instead, the absence of a National Action Plan and the exclusion of women at the strategic level of decision-making highlight that their participation has remained operational rather than transformative. This gap undermines the long-term effectiveness of Israel’s counterterrorism strategy and weakens the prospects for inclusive and sustainable security and peace negotiations.

This research concludes that while Israel has achieved tactical gains in its war against Hamas, the absence of a coherent political track, its failure to confront Hamas as an entrenched ideology, and its disregard for the ethical obligations of Just War Theory and mass atrocity prevention have rendered its campaign both counterproductive and unjustly fought.

As a democracy, Israel bears the responsibility to uphold higher moral standards—not only for ethical reasons, but also for strategic purposes. When the state and its soldiers accept the risks involved in minimizing harm to civilians, the moral blame for civilian casualties should fall on those who violate the rules of war—[cxxxi]namely, the terrorist actors who exploit civilian populations as human shields. Ultimately, the elimination of Hamas and the pursuit of lasting peace and security will not be realized through annihilation, but through the deliberate balancing of military force, political vision, and diplomatic engagement.

[i] Daniel Byman, Riley McCabe, Alexander Palmer, Catrina Doxsee, Mackenzie Holtz, and Delaney Duff. “Hamas’s October 7 Attack: Visualizing the Data.” CSIS. Accessed May 4, 2025 at https://www.csis.org/analysis/hamass-october-7-attack-visualizing-data.

[ii] Jeremy Sharon, “Netanyahu: Won’t Surrender to Hamas by Ending War to Get Back Hostages; Can’t Trick Hamas Either .” The Times of Israel. Accessed May 5, 2025 at https://www.timesofisrael.com/netanyahu-claims-impossible-to-resume-gaza-war-if-deal-reached-to-free-all-hostages/.

[iii] Robert A. Pape, “Hamas Is Winning.” Foreign Affairs, April 6, 2025 at https://www.foreignaffairs.com/israel/middle-east-robert-pape.

[iv] Max Rodenbeck, Mairav Zonszein, and Amjad Iraqi. “Is the Gaza War Approaching Its Endgame?” International Crisis Group. Accessed May 5, 2025 at https://www.crisisgroup.org/middle-east-north-africa/east-mediterranean-mena/israelpalestine/gaza-war-approaching-its-endgame.

[v] Bruce Hoffman, Inside Terrorism, (New York: Columbia Univ. Press, 2017), p. 154

[vi] Kali Robinson, “What Is Hamas?” Council on Foreign Relations, 2024 at https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/what-hamas.

[vii] Ibid

[viii] Hoffman, Inside Terrorism, p. 155

[ix] Matthew Levitt, Hamas: Politics, Charity, and terrorism in the service of Jihad. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2006), p. 8

[x] The Avalon Project. “The Covenant of the Islamic Resistance Movement.” Yale Law School, 1988. https://avalon.law.yale.edu/20th_century/Hamas.asp.

[xi] Ibid

[xii] Bruce Hoffman, “Understanding Hamas’s Genocidal Ideology.” The Atlantic, October 13, 2023 at https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2023/10/hamas-covenant-israel-attack-war-genocide/675602/.

[xiii] Byman, Daniel. A high price: The triumphs and failures of Israeli counterterrorism. (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011) p. 377

[xiv] Robinson, “What Is Hamas?

[xv] Ibid

[xvi] Levitt, Hamas, p. 34

[xvii] Kali Robinson, “What Is Hamas?”

[xviii] Ibid

[xix] Shira Rubin and Joby Warrick, “Hamas envisioned deeper attacks, aiming to provoke an Israeli war.” The Washington Post, November 13, 2023 at

https://www.washingtonpost.com/national-security/2023/11/12/hamas-planning-terror-gaza-israel

[xx] Human Rights Council. “Report of the Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Occupied Palestinian Territory, Including East Jerusalem, and Israel – Advance Unedited Version (A/HRC/56/26) .” United Nations, May 27, 2024. https://www.un.org/unispal/document/coi-report-a-hrc-56-26-27may24/.

[xxi] Ibid

[xxii] Bruce Hoffman, “The October 7, 2023 Attacks 16 Months Later: Lessons Learned” (lecture, Security Studies, Georgetown University, Washington, DC, March, 10, 2025).

[xxiii] Human Rights Council. “Report of the Independent International Commission of Inquiry

[xxiv] Hoffman, “The October 7, 2023 Attacks 16 Months Later: Lessons Learned”

[xxv] Human Rights Council. “Report of the Independent International Commission of Inquiry

[xxvi] Dado Center for Interdisciplinary Military Studies. “Swords of Iron’ War.” (Israel: Ministry of Defense – Publishing House, 2024) p. 24

[xxvii] Byman, A High Price, p. 375

[xxviii] Ynet News, “Israel Warns Hizbullah War Would Invite Destruction.” Ynetnews, October 3, 2008 at https://www.ynetnews.com/articles/0,7340,L-3604893,00.html.

[xxix] Gabi Siboni “Disproportionate Force: Israel’s Concept of Response in Light of the Second Lebanon War.” The Institute for National Security Studies, October 2, 2008 at https://www.inss.org.il/publication/disproportionate-force-israels-concept-of-response-in-light-of-the-second-lebanon-war/.

[xxx] ICRC, “Article 51 – Protection of the Civilian Population.” ICRC. Accessed May 6, 2025. https://ihl-databases.icrc.org/en/ihl-treaties/api-1977/article-51.

[xxxi] IMEU, “Explainer: The Dahiya Doctrine & Israel’s Use of Disproportionate Force.” Institute for Middle East Understanding, July 31, 2024 at https://imeu.org/article/the-dahiya-doctrine-and-israels-use-of-disproportionate-force.

[xxxii] Gabi Siboni, “Disproportionate Force: Israel’s Concept of Response in Light of the Second Lebanon War.”

[xxxiii] The Times of Israel. “Eisenkot Charges Israel’s Plan for Gaza War ‘went Very Seriously Wrong’ Due to Ambitions of Far-Right Lawmakers.” The Times of Israel, November 20, 2024 at https://www.timesofisrael.com/liveblog_entry/eisenkot-charges-israels-plan-for-gaza-war-went-very-seriously-wrong-due-to-ambitions-of-far-right-lawmakers/.

[xxxiv] Ibid

[xxxv] Netanyahu, Benjamin. “PM Netanyahu’s Remarks at the Start of the Government Meeting.” Ministry of Foreign Affairs, March 30, 2025 at https://www.gov.il/en/pages/pm-netanyahu-s-remarks-at-the-start-of-the-government-meeting-17-apr-2024.

[xxxvi] Max Rodenbeck, Mairav Zonszein, and Amjad Iraqi, “Is the Gaza War Approaching Its Endgame?”

[xxxvii] Donald Trump, “President Trump Holds a Press Conference with Prime Minister Netanyahu of Israel.” The White House, February 4, 2025. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MvheR2KJYyY.

[xxxviii] Colin Gray, “Why Strategy is Difficult,” Joint Forces Quarterly (Summer 1999): p. 9.

[xxxix] Natan Sachs, “Israel’s Strategic Choice.” Brookings, May 17, 2024 at https://www.brookings.edu/articles/israels-strategic-choice/.

[xl] Ibid

[xli] Max Rodenbeck, Mairav Zonszein, and Amjad Iraqi, “Is the Gaza War Approaching Its Endgame?”

[xlii] Benjamin Netanyahu, “Netanyahu Outlines Vision of a ‘demilitarized’ Gaza after Israeli Defeat of Hamas.” PBS News, July 24, 2024 at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=50opga6nayw.

[xliii] Lloyd J. Austin III. “‘A Time for American Leadership’: Remarks by Secretary of Defense Lloyd J. Austin III at T.” U.S. Department of Defense, December 2, 2023 at https://www.defense.gov/News/Speeches/Speech/Article/3604755/a-time-for-american-leadership-remarks-by-secretary-of-defense-lloyd-j-austin-i/.

[xliv] Center for PrevenCenter for Preventive Actiontive Action. “Israeli-Palestinian Conflict .” Council on Foreign Relations, March 31, 2025 at https://www.cfr.org/global-conflict-tracker/conflict/israeli-palestinian-conflict.

[xlv] Ameneh Mehvar, and Nasser Khdour Nasser Khdour. “After a Year of War, Hamas Is Militarily Weakened – but Far from ‘Eliminated.’” ACLED, October 6, 2024 at https://acleddata.com/2024/10/06/after-a-year-of-war-hamas-is-militarily-weakened-but-far-from-eliminated/.

[xlvi] Ibid

[xlvii] Ibid

[xlviii] Byman, A High Price, p.365

[xlix] Audrey Kurth Cronin. “Sinwar Is Dead, but Hamas Will Survive.” Foreign Affairs, October 19, 2024 at https://www.foreignaffairs.com/israel/yahya-sinwar-dead-hamas-will-survive-audrey-kurth-cronin.

[l] Ibid

[li] Max Rodenbeck, Mairav Zonszein, and Amjad Iraqi, “Is the Gaza War Approaching Its Endgame?”

[lii] Ibid

[liii] Eugenia Yosef, Kareem Khadder, and Irene Nasser. “Israel Announces Expansion of Military Operation in Gaza to Seize ‘large Areas’ of Land, Ordering Residents to Leave.” CNN, April 2, 2025 at https://www.cnn.com/2025/04/02/middleeast/israel-expands-military-operations-gaza-intl-hnk/.

[liv] Isabel Kershner. “Israel Shifts Goal Posts in Gaza War.” The New York Times, April 3, 2025. https://www.nytimes.com/2025/04/03/world/middleeast/israel-hamas-gaza-military-objectives.html.

[lv] John Spencer, “Israel’s New Approach to Tunnels: A Paradigm Shift in Underground Warfare.” Modern War Institute – West Point, December 2, 2024 at https://mwi.westpoint.edu/israels-new-approach-to-tunnels-a-paradigm-shift-in-underground-warfare/.

[lvi] Yuval Levy. “Around 75% of Hamas’s Tunnels in Gaza Not Destroyed by IDF.” The Jerusalem Post, April 9, 2025 at https://www.jpost.com/breaking-news/article-849430.

[lvii] John Spencer, “Israel’s New Approach to Tunnels”

[lviii] Ibid

[lix] Ibid

[lx] Ibid

[lxi] Ibid

[lxii] Ibid

[lxiii] Michael Walzer, Just and Unjust Wars: A moral argument with historical illustrations. (New York: Basic Books, 2015) p. 197

[lxiv] Fanon, Frantz. The wretched of the earth: Frantz fanon. (New York: Grove Press, 2004)

[lxv] Michael Walzer, Just and Unjust Wars, p. 205

[lxvi] IEP. “Just War Theory.” Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Accessed May 5, 2025 AT https://iep.utm.edu/justwar/.

[lxvii] David Luban, “What Would Augustine Do?” Boston Review, June 6, 2012 at https://www.bostonreview.net/articles/david-luban-the-president-drones-augustine-just-war-theory/.

[lxviii] Michael Walzer, Just and Unjust Wars, p. 21

[lxix] United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. “Definitions: Types of Mass Atrocities.” United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Accessed May 6, 2025 at https://www.ushmm.org/genocide-prevention/learn-about-genocide-and-other-mass-atrocities/definitions.

[lxx] Peter Savodnik, “What Makes a War Just?” The Free Press, October 18, 2023 at https://www.thefp.com/p/what-makes-a-war-just.

[lxxi] ICC. “Situation in the State of Palestine: ICC Pre-Trial Chamber I Rejects the State of Israel’s Challenges to Jurisdiction and Issues Warrants of Arrest for Benjamin Netanyahu and Yoav Gallant.” International Criminal Court, November 21, 2024 at https://www.icc-cpi.int/news/situation-state-palestine-icc-pre-trial-chamber-i-rejects-state-israels-challenges.

[lxxii] OCHA. “Reported Impact Snapshot: Gaza Strip (20 August 2025).” United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs – Occupied Palestinian Territory, August 25, 2025 at https://www.ochaopt.org/content/reported-impact-snapshot-gaza-strip-20-august-2025.

[lxxiii] United Nations. “Adopting Resolution 2735 (2024) with 14 Votes in Favour, Russian Federation Abstaining, Security Council Welcomes New Gaza Ceasefire Proposal, Urges Full Implementation” United Nations – Meetings Coverage and Press Releases, June 10, 2024. https://press.un.org/en/2024/sc15723.doc.htm.

[lxxiv] IDF. “Everything You Need to Know About Hamas’ Underground City of Terror.” Israel Defense Forces, July 31, 2014 at https://www.idf.il/en/mini-sites/the-hamas-terrorist-organization/everything-you-need-to-know-about-hamas-underground-city-of-terror/.

[lxxv] Bruce Hoffman, “Terrorism: Definitions and Distinctions” (lecture, Security Studies, Georgetown University, Washington, DC, January, 8, 2025).

[lxxvi] ICRC. “Rule 53. The Use of Starvation of the Civilian Population as a Method of Warfare Is Prohibited.” ICRC. Accessed May 6, 2025. https://ihl-databases.icrc.org/en/customary-ihl/v1/rule53.

[lxxvii] Center for PrevenCenter for Preventive Actiontive Action, “Israeli-Palestinian Conflict.

[lxxviii] Amnesty International. “Israel/ Opt: Investigate Killings of Paramedics and Rescue Workers in Gaza .” Amnesty International, April 1, 2025 at https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2025/04/israel-opt-investigate-killings-of-paramedics-and-rescue-workers-in-gaza/

[lxxix] WCK. “WCK Calls for Independent Investigation into IDF Strikes.” World Central Kitchen, April 4, 2024. https://wck.org/news/idf-investigation.

[lxxx] CPJ. “Journalist Casualties in the Israel-Gaza War.” Committee to Protect Journalists, August 25 2025. https://cpj.org/2025/02/journalist-casualties-in-the-israel-gaza-conflict/.

[lxxxi] Noël Mfuranzima, “Jus Post Bellum: Scope and Assessment of the Applicable Legal Framework.” International Review of the Red Cross 106, no. 927 (2024): 1250–63. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1816383124000225.

[lxxxii] Laura E. Alexander and Kristopher Norris. “Jus Post Bellum and Responsibilities to Refugees and Asylum Seekers.” E-International Relations, February 6, 2020 at https://www.e-ir.info/2020/02/06/jus-post-bellum-and-responsibilities-to-refugees-and-asylum-seekers/.

[lxxxiii] Congress.gov. “Israel and Hamas Conflict In Brief: Overview, U.S. Policy, and Options for Congress.” May 6, 2025 at https://www.congress.gov/crs-product/R47828.

[lxxxiv] Josh Paul, and Noura Erakat. “Report of the Independent Task Force on National Security Memorandum-20 Regarding Israel.” Just Security, April 24, 2024 at https://www.justsecurity.org/94980/task-force-national-security-memorandum-20/.

[lxxxv] ICC. “Situation in the State of Palestine: ICC Pre-Trial Chamber I Issues Warrant of Arrest for Mohammed Diab Ibrahim al-Masri (DEIF).” International Criminal Court, November 21, 2024 at https://www.icc-cpi.int/news/situation-state-palestine-icc-pre-trial-chamber-i-issues-warrant-arrest-mohammed-diab-ibrahim.

[lxxxvi] ICC. “Situation in the State of Palestine: Warrants of Arrest for Benjamin Netanyahu and Yoav Gallant.”

[lxxxvii] Zvobgo, Kelebogile. “Biden’s ICC Hypocrisy Undermines International Law.” Brookings, December 20, 2024 at https://www.brookings.edu/articles/bidens-icc-hypocrisy-undermines-international-law/.

[lxxxviii] Office on Genocide Prevention and the Responsibility to Protect. “About the Responsibility to Protect.” United Nations. Accessed May 6, 2025 at https://www.un.org/en/genocide-prevention/responsibility-protect/about.

[lxxxix] Gareth Evans, “The Solution: From ‘The Right to Intervene’ to ‘The Responsibility to Protect.’” In The Responsibility to Protect: Ending Mass Atrocity Crimes Once and For All, 31–54. Brookings Institution Press, 2008. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7864/j.ctt4cg7fp.6.

[xc] Scott Straus, Fundamentals of Genocide and Mass Atrocity Prevention. (United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, 2016) p. 76

[xci] Francesa Albanese. “HRC55 | Francesca Albanese Alleges Israeli Genocide Against Palestinians in Gaza.” UN Human Rights Council, March 26, 2024 at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3XrwNGWF108&t=100s.

[xcii] David Moshman, Conceptual constraints on thinking about genocide. Journal of Genocide Research 3 (3): (2001). 431–50. doi:10.1080/14623520120097224.

[xciii] Gregory H. Stanton. “Ten Stages of Genocide.” Genocide Watch, 1996 at https://www.genocidewatch.com/tenstages.

[xciv] Francesca Albanese. “Anatomy of a Genocide – Advance Unedited Version (A/HRC/55/73).” United Nations Human Rights Council, March 4, 2024 at https://www.un.org/unispal/document/anatomy-of-a-genocide-report-of-the-special-rapporteur-on-the-situation-of-human-rights-in-the-palestinian-territory-occupied-since-1967-to-human-rights-council-advance-unedited-version-a-hrc-55/.

[xcv] Ibid

[xcvi] Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Occupied Palestinian Territory. “Report of the Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Occupied Palestinian Territory, Including East Jerusalem, and Israel – Advance Unedited Version (A/HRC/56/26).” United Nations Human Rights Council, May 27, 2024 at https://www.un.org/unispal/document/coi-report-a-hrc-56-26-27may24/.

[xcvii] Scott Straus, Fundamentals of Genocide and Mass Atrocity Prevention, p.76.

[xcviii] VOANews. “Netanyahu to US Lawmakers: Demilitarized, Deradicalized Gaza Will Bring Peace.” Voice of America, July 24, 2024 at https://youtu.be/Cfxi9Yc6DfA?t=102.

[xcix] Grace Condon and Frankie Condon, “Genocide Is Never Justifiable: Israel and Hamas in Gaza.” Genocide Watch, February 4, 2024 at https://www.genocidewatch.com/single-post/genocide-is-never-justifiable-israel-and-hamas-in-gaza.

[c] Mairav Zonszein. “Israel Aims to ‘deradicalise’ Gaza but It Should Deradicalise Itself.” The National, January 5, 2024 at https://www.thenationalnews.com/weekend/2024/01/05/israel-aims-to-deradicalise-gaza-but-it-should-deradicalise-itself-too/.

[ci] Ibid

[cii] Byman, A High Price, p. 375.

[ciii] Audrey Kurth Cronin. “How Hamas Ends: A Strategy for Letting the Group Defeat Itself.” Foreign Affairs, June 3, 2024 at http://foreignaffairs.com/israel/how-hamas-ends-gaza.

[civ] Ibid

[cv] Ibid

[cvi] Daniel Byman. “A War They Both Are Losing: Israel, Hamas and the Plight of Gaza.” International Institute for Strategic Studies, June 4, 2024 at https://www.iiss.org/online-analysis/survival-online/2024/06/a-war-they-both-are-losing-israel-hamas-and-the-plight-of-gaza/.

[cvii] Ibid

[cviii] Daniel Byman. “Stuck in Gaza: Six Months After October 7, Israel Still Lacks a Viable Strategy.” Foreign Affairs, April 5, 2024 at https://www.foreignaffairs.com/middle-east/hamas-israel-stuck-gaza.

[cix] Toby Matthiesen. “How Gaza Reunited the Middle East.” Foreign Affairs, February 9, 2024 at https://www.foreignaffairs.com/middle-east/how-gaza-reunited-middle-east.

[cx] BBC. “Israel-Colombia: Petro Anuncia Que Colombia Romperá Relaciones Con Israel Por La Ofensiva En Gaza.” BBC News Mundo, May 1, 2024 at https://www.bbc.com/mundo/articles/c84z30mle48o.

[cxi] CNN. “Estos Son Los Países Que Han Roto Relaciones Diplomáticas Con Israel Por La Guerra Contra Hamas En Gaza y Otros Motivos.” CNN Mundo, May 4, 2024 at https://cnnespanol.cnn.com/2024/05/04/paises-rompieron-relaciones-israel-gaza-orix.

[cxii] Ibid

[cxiii] Embassy of Israel in Mexico. “Comunicado Referente a Las Declaraciones Del Presidente de México, Andrés Manuel López Obrador.” Embassy of Israel in Mexico, October 9, 2023. https://twitter.com/IsraelinMexico/status/1711522767068148206.

[cxiv] Secretaría de Relaciones Exteriores. “El Gobierno de México Expresa Su Máxima Preocupación Por Conflicto Entre Israel y Palestina y Condena Todo Acto En Contra de Civiles.” Gobierno de México, October 8, 2023 at https://www.gob.mx/sre/prensa/el-gobierno-de-mexico-expresa-su-maxima-preocupacion-por-conflicto-entre-israel-y-palestina-y-condena-todo-acto-en-contra-de-civiles.

[cxv] Emmanuel Nahshon Schlanger. “What Are the Challenges within Israel’s Public Diplomacy?” The Jerusalem Post , December 29, 2024 at https://www.jpost.com/opinion/article-835181.

[cxvi] Ibid

[cxvii] Omer Dostri. “Israel’s Struggle with the Information Dimension and Influence Operations during the Gaza War.” Army University Press, June 2024 at https://www.armyupress.army.mil/journals/military-review/online-exclusive/2024-ole/dr-dostri-israel-gaza-war/.

[cxviii] Daniel Byman, and Emma McCaleb. “Understanding Hamas’s and Hezbollah’s Uses of Information Technology.” Center for Strategic & International Studies, July 31, 2023 at https://www.csis.org/analysis/understanding-hamass-and-hezbollahs-uses-information-technology.

[cxix] Human Rights Watch. “Meta’s Broken Promises: Systemic Censorship of Palestine Content on Instagram and Facebook.” Human Rights Watch, December 21, 2023 at https://www.hrw.org/report/2023/12/21/metas-broken-promises/systemic-censorship-palestine-content-instagram-and.

[cxx] Ibid

[cxxi] Ibid

[cxxii] NATO. “NATO’s Approach to Counter Information Threats.” NATO, February 3, 2025. https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/topics_219728.htm.

[cxxiii] Isabel Kershner. “Israeli Women Fight on Front Line in Gaza, a First .” The New York Times, January 19, 2024. https://www.nytimes.com/2024/01/19/world/middleeast/israel-gaza-women-soldiers.html.

[cxxiv] Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom. “National Action Plans: At a Glance.” PeaceWomen.org, https://1325naps.peacewomen.org/

[cxxv] NATO. “Exclusive interview with UNSCR 1325 as she turns 19.” NATO, October 31, 2019. https://www.nato.int/docu/review/articles/2019/10/31/exclusive-interview-with-unscr-1325-as-she-turns-19/

[cxxvi] Isabel Kershner. “Israeli Women Fight on Front Line in Gaza, a First .” The New York Times, January 19, 2024. https://www.nytimes.com/2024/01/19/world/middleeast/israel-gaza-women-soldiers.html.

[cxxvii] Ibid

[cxxviii] United Nations Security Council. “Resolution 2242 (2015).” United Nations, October 13, 2025. https://www.securitycouncilreport.org/atf/cf/%7B65BFCF9B-6D27-4E9C-8CD3-CF6E4FF96FF9%7D/s_res_2242.pdf

[cxxix] Center for Women in the Public Sphere. “Promoting an Israeli Action Plan for the Implementation of United Nations Security Council Resolution 1325.” World Justice Project. https://worldjusticeproject.org/our-work/programs/promoting-israeli-action-plan-implementation-united-nations-security-council

[cxxx] Itach-Maaki. “1325 – Collecting Women’s testimonies for policy change.” Itach-Maaki Women Lawyers for Social Justice. https://www.itach.org.il/1325/testimonies/?lang=en

[cxxxi] Michael Walzer, Just and Unjust Wars, p. xxi