Introduction

On 7 December 1941, when Japanese forces launched a surprise attack on the naval base at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, the United States could no longer stand by as World War II consumed the globe. American servicemen and women set sail for both the European and Pacific theaters. While the grueling battle to unseat Hitler and defeat Nazi Germany took center stage, the Pacific theater witnessed some of the most violent fighting of the war. One of the key battlegrounds in the Pacific, heavily occupied by Japanese forces, was Burma.

CONTACT Stephen Hill | Stephen.D.Hill40@proton.me

The views expressed in this publication are entirely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views, policy, or position of United States Government, Department of Defense, or United States Special Operations Command. © 2023 Arizona State University

The only land link remaining to China—the liberation of Burma and the reopening of the Burma Road that led into China—became a strategic objective for the United States. Japanese forces in Burma had already pushed British and American-led Chinese troops out of the country, using the dense jungle and rugged terrain to their advantage. A new operational concept was required to confront the expanding Japanese empire in Burma and reopen supply lines to a faltering China.

Developed by British Brigadier Orde Wingate, long-range penetration was just the operational concept needed. American and British leadership believed in Wingate’s theory and committed resources—both in manpower and funding—with the aim of pushing Japan out of Burma and reestablishing the land link with China. The American fighting force created for this mission has gone by many names, including Galahad, the 5307th Composite Unit (Provisional), and Merrill’s Marauders. Names aside, one thing is clear: the men of the 5307th made a strategic impact on the China-Burma-India (CBI) theater by employing the operational concept of long-range penetration.

Merrill’s Marauders earned their place in history by enduring dense jungle, unforgiving terrain, widespread illness and injury, fierce combat, and a relentless enemy. Through all this hardship, the legacy of American special operations was born.

The China-Burma-India Theater

By December 1941, Germany had blitzkrieged its way across Europe. Hitler’s Third Reich had rolled through Holland, Belgium, Norway, Yugoslavia, and Greece, and was well on its way to taking what remained of France.[1] The Germans, however, were not the only ones occupying vast territory. At the same time, the Japanese had invaded an area twice the size of Germany’s wartime footprint.[2]

China was the crown jewel of Imperial Japan. The expansive country promised an enormous market for Japanese goods, a wide array of exploitable resources, a number of shipping hubs to facilitate Japan’s rise, and a strategic buffer between the Japanese homeland and the Soviet Union.[3] Japan pursued a strategy of isolation and began to envelop China.

Imperial forces captured Indochina (present-day Vietnam), effectively cutting off land-based supply lines into China. The only remaining route was the Burma Road.[4] In rapid succession, Japan took Hong Kong, then Borneo and Thailand. The noose around China was tightening. Although the Allies had adopted a “Europe First” strategy in World War II, Japan’s advance through Burma—culminating in the capture of Rangoon—forced them to reassess the strategic importance of the CBI theater.

Just days before the Japanese captured Rangoon—and soon after, the rest of Burma—the United States had deployed 440 military personnel, under the leadership of Major General Joseph Stilwell, to help train and equip more than three million Chinese troops.[5] Stilwell’s efforts were soon thwarted. By mid-1942, Japanese forces had established control over Burma and expelled the American, British, and Chinese troops.

The isolation of China grew even more critical after the Japanese severed the last land route into the country. The United States could not bear the prospect of losing China from the Allied war effort—or of being outmaneuvered by Japan. As Gavin Mortimer explains, “Roosevelt was determined not just to restore the prestige of the Allies, but to keep China an active partner in the alliance. It was envisaged that further down the line, China would provide American bomber aircraft with the bases from which to attack the Japanese mainland.”[6] The U.S. had to act fast or risk losing China. Multiple Allied conferences were held to address the CBI theater, and gradually, a cohesive strategy began to emerge.

The Strategic Aims of the U.S. in Burma

Halting Japan’s relentless expansion across the Asian continent became a matter of grave importance for the United States. By mid-1942, fear of Japanese imperial ambitions had pushed the China-Burma-India (CBI) theater into strategic focus. Donovan Webster, in The Burma Road, explains the Allied approach to the region:

“The entire point of the China theater and, later, CBI was to protect what remained of Asia for Britain, China, and the United States. Initially, however, its sole objective was to keep China in the war and India under colonial British rule, since both nations functioned as the gateway not only to Central Asia, but as the obvious path for a land-based link between Japan and Germany.”[7]

Keeping China in the war would prove more difficult and time-consuming than U.S. strategists had anticipated.

The United States viewed China as an untapped resource in the fight against Japan. With its geographic position and vast pool of manpower, China represented a potential asset to American war planners.[8] All that was needed, they believed, was training and equipment. Even before formally entering the war after the attack on Pearl Harbor, the U.S. had been sending Lend-Lease material to China,[9] with General Stilwell’s training programs soon to follow.[10]

However, in the CBI theater, the U.S. was challenged not only by the Japanese but also by reluctance and resistance from both its British and Chinese allies. British leadership, primarily focused on the European and Mediterranean fronts, showed little initial interest in liberating Burma or reestablishing a land route to China. Unlike the Americans, they did not share enthusiasm for the potential professionalization of Chinese military forces. From the British perspective, opening a land corridor to China would contribute little to defeating Japan.[11]

For the Chinese, internal struggles between the established Kuomintang party, presided over by President Chiang K’ai-shek, and Communist factions in the country undermined American efforts. Even though a truce was formed between the Chinese factions when Japanese expansionist elements thrust Japan’s armed forces into a “full-scale but undeclared war against China” in 1937, it was not long before infighting resumed.[12] This internal turbulence resulted in a defensive posture from President Chiang K’ai-shek.

Bjorge articulates Chinese apprehension, writing:

China’s position was that of Chiang K’ai-shek, president and commander of the Chinese Army. His government was weak and faced many internal challenges, especially from the Communists. He did not want to see his military forces consumed in battles with the Japanese because he would then have fewer troops to support him in internal disputes…As Stilwell told General George C. Marshall, Chief of Staff of the U.S. Army in mid-1943, ‘[Chiang] did not want the regime to have a large, efficient ground force for fear that its commander would inevitably challenge his position as China’s leader.’[13][14]

The reluctance of the Chinese to provide significant numbers, combined with British indifference to the Burma theater, weighed heavily on the U.S. ability to produce results. And with the European theater monopolizing much of the country’s resources, a solution in Burma was pursued—albeit on a shoestring budget. Regardless, the U.S. endeavored to reopen supply lines to China.

Japanese control of Burma and the ports surrounding China effectively cut off supplies to the country. Japanese aircraft patrolled aerial supply lines, while ground forces barred vehicle-borne resupply. Without a healthy flow of Lend-Lease materials from the U.S., the giant of the Asian continent was withering. Plagued by internal turmoil and strife between the current leadership and Communist factions, China was in no condition to fight off the encroaching Japanese threat. The U.S. feared that if China fell, the Japanese would become insatiable in their expansion.

One aerial route remained available to Allied forces. Known as the Hump Route, the airbridge from Ledo to Assam provided minimal supplies to the beleaguered Chinese.[15] The 700-mile route, which took aircrews over the Himalayas, was treacherous and could not fulfill the required tonnage of supplies to successfully maintain Chinese forces under Stilwell.[16] The only conceivable way to deliver the 45,000 tons of Lend-Lease material was via land. Reopening the Burma Road was imperative.[17]

The U.S. championed the retaking of Burma during coalition conferences held in 1943. At the Casablanca Conference, the U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff “put an offensive to retake Burma high on the conference agenda and obtained British agreement to conduct the operation in the winter of 1943–1944.”[18] Developments in the European theater, however, led to an agreement during the Trident Conference that only Northern Burma would be the objective of the coming offensive. U.S. strategists continued to emphasize to attendees the importance of a land link to China, regardless. [19]

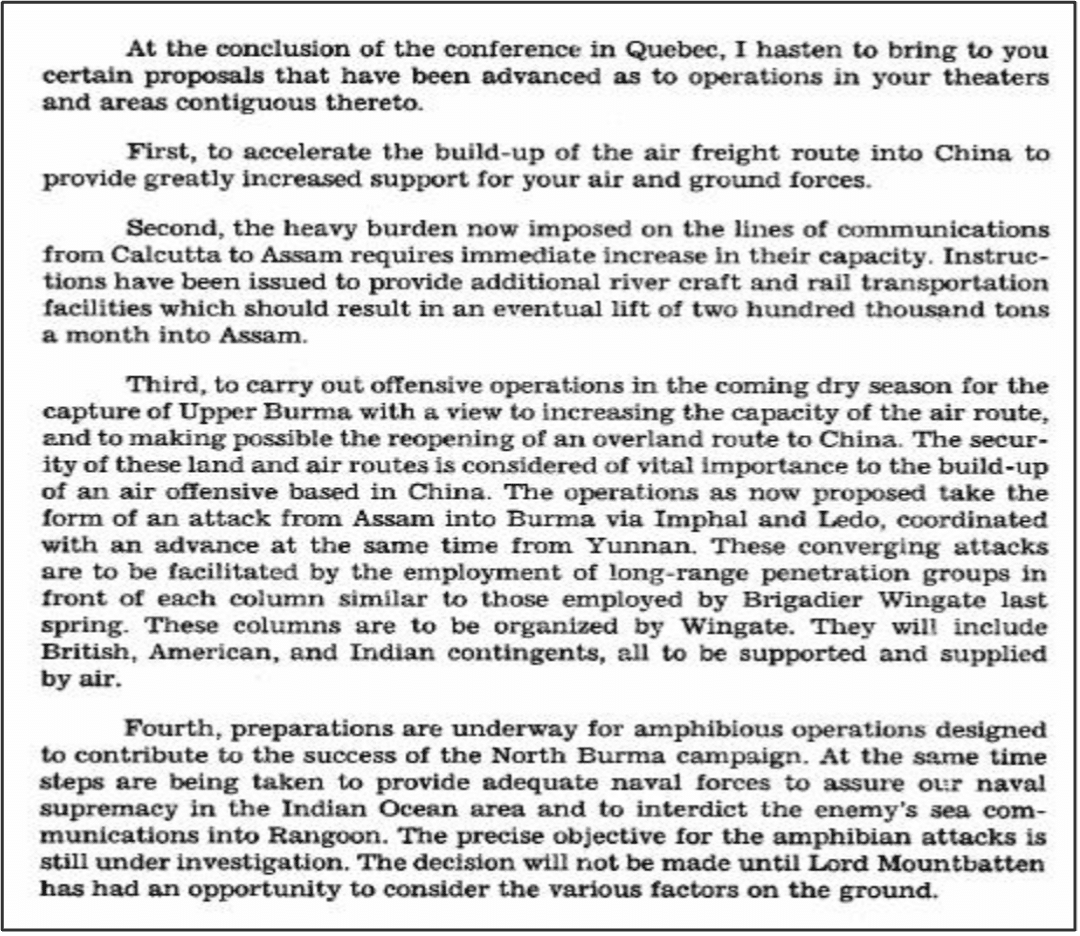

It was not until the Quadrant Conference of August 1943 that a final strategy was put to paper. Four objectives were established (as shown in Figure 1), which would result in the creation of an American ground force tasked with retaking Northern Burma and reopening the Burma Road.

Figure 1. The Quadrant Conference, August 1943. Source: Joint History Office, Government Publishing Office, October 2017

Merrill’s Marauders

The 5307th Composite Unit (Provisional), known shortly after its formation as Merrill’s Marauders—a moniker given in honor of the unit’s initial commander, Brigadier General Frank D. Merrill[20]—was brought into existence in August of 1943. The unit, initially code-named Galahad, was formed on paper at the Quebec Conference, also referred to as the Quadrant Conference, when the need for an American ground force in Burma was pressed upon the Allied leadership.[21]

One of America’s precursors to modern Special Operations Forces, the 5307th owes its genesis to a British officer. Then-Brigadier Orde Charles Wingate, at the invitation of Winston Churchill,[22] presented to the attendees of the Conference an operational concept he had experimented with in Northern Burma earlier that year. The use of long-range penetration groups, in concert with conventional ground forces, could provide the foothold required to drive the Japanese out of Burma and reestablish supply lines to China.

The minutes of the Quebec Conference explain:

“The British Chiefs of Staff had considered proposals put forward by Brigadier Wingate for the increased employment of long-range penetration groups in conjunction with the main advances. These groups relied on the Japanese outflanking tactics, but whereas the Japanese outflanking movements consisted of four or five-mile sweeps, Wingate’s method used 40 or 50-mile sweeps and used units of the size of a brigade group. These groups took pack transport and wireless and could, when necessary, be maintained from the air. They would reach far into the area of the Japanese lines of communication in conjunction with the main advances … He [the British Chief of Staff] felt that the United States Chief of Staff might wish to hear from Brigadier Wingate his views on the use of long-range penetration groups.”[23]

As a result, American leadership—impressed by Prime Minister Churchill’s confidence in Wingate’s proposal and in need of a tactic to turn the tide in Burma—authorized the creation of a 3,000-man long-range penetration group to be trained by Wingate and operate in the thick jungles of Burma to unseat the Imperial Japanese.[24] Initial planning also had Wingate commanding the American force; however, subsequent changes placed the Marauders under American General Stilwell’s command.[25]

Thus, the 5307th Composite Unit (Provisional), code-named Galahad, was born. The operational concept pitched by Brigadier Wingate was not, however, developed solely in the jungles of Burma. Wingate had been slowly building his concept for long-range penetration groups since his first command as a British officer. It was this drawn-out vetting period, conducted by Orde Wingate, that laid the foundation for Merrill’s Marauders’ successes in the CBI.

The Makings of an Operational Concept

The inspiration for the 5307th Composite Unit (Provisional) was drawn from the tactics of one British officer who endeavored to rid British Burma of the Imperial Japanese.[26] Orde Charles Wingate, an ardent believer in the Old Testament and a passionate champion of long-range penetration operations [27], set in motion an operational concept that he had been working to develop since early in his military career.

Wingate first pondered the effects of small groups of soldiers conducting long-distance footborne operations well outside the reach of conventional lines of communication while he was a lieutenant—filling a major’s billet—commanding an infantry company composed of Sudan Defence Forces and the East Arab Corps in Kassala Province, Sudan.[28] The remote location and lack of accountability to the higher command headquartered in Gedaref afforded Wingate an unprecedented amount of leeway while conducting operations for the Crown.

Jon Diamond explains, the “isolated backwater allowed Wingate to exhibit command initiatives and develop military principles about small groups of soldiers surviving in a desolate, inhospitable environment, which would have been almost impossible for his rank in the regular British Army. Training, fitness, and field craft became his credos, which would enable his troops to remain far from garrison without [lines of communication].”[29]

Wingate even experimented with ground-to-air coordination with the Royal Air Force—a tactic that would later be expanded and utilized by both Wingate and the Marauders in Burma.

Wingate further refined his concept while leading anti-poaching patrols in Ethiopia and combating the Arab revolt in Palestine. He was impressed by the poachers’ ability to scatter and reform when threatened by attack. As a brigadier, Wingate would implement this tactic in Burma, dubbing it “dispersal and rendezvous.”[30] IIn Palestine, Wingate’s creation of the Special Night Squads—made up of Jewish paramilitary forces led by British officers and NCOs—was another testament to his unorthodox way of fighting.[31]

By the time World War II had begun, the freshly minted Captain Wingate had already created a conceptual framework for his brand of operations: long-range penetration. In the early 1940s, Wingate crossed the Sudan–Ethiopian border with a force of around 3,000 men he called the Gideon Force, after the biblical warrior of Old Testament lore,[32] and—with deception, harassment tactics, and guerrilla warfare—was able to defeat an Italian force of some 36,000.[33]

His Gideon Force was disbanded in the summer of 1941; however, it was not long before Wingate began organizing another long-range penetration unit. Pulled into the Burma theater by Archibald Wavell, the former commander of British troops in Palestine and admirer of Wingate’s unorthodox tactics, Wingate set to work transforming his new command—the 77th Indian Brigade—into a long-range penetration force.[34]

After a period of rigorous training, Wingate’s force, now nicknamed “The Chindits” (after the Burmese half-lion, half-dragon temple guardian statues),[35] was deployed in what came to be known as Operation Longcloth. Originally designed to operate in unison with three Chinese units tasked with liberating Burma, the Chindits struck out into the jungle alone. The Chinese forces were in no shape to provide support at the front, while Wingate’s men worked the vulnerable rear echelons. Against advice from higher command to wait, Wingate marched his men deep into Burma.[36]

Wingate’s sojourn into Japanese-held territory was viewed in conflicting lights when his columns—ordered to disperse into small groups and rally across the border in India—returned after venturing too far behind enemy lines. Of the raid and General William Slim’s response, Webster noted:

“Of the three thousand Chindits who went into Burma, only 2,182 came out—and only six hundred of those men were ever fit for military service again. He also noted that, while damage was done to the Japanese rail and communications systems by the Chindits mission, only an estimated 205 Japanese were killed. Because of these inequitable casualty rates, not to mention the costs in airpower and equipment lost for what was ultimately only a short-term disruption to the flow of Japanese troops, information, and goods, Slim was forced to assess the Chindit raid as a failure.”[37]

General Slim’s assessment, however, did not stop positive propaganda about the Chindits’ exploits from circling the globe, giving hope to Allied leaders. As noted above, Winston Churchill took a leading interest in Wingate’s operational concept, and through that interest and championship, the 5307th Composite Unit (Provisional) was brought to life.

Recruiting, Organization, and Training

Born on paper, Galahad needed living, breathing troopers to fill its ranks. Recruitment for the classified unit was conducted under a cloak of secrecy. Even the name Galahad was classified at the Secret level and known to only a few, not reaching the founding members of the unit until well into their training cycle.[38] Notice was posted for the new unit under the guise of the 1688th Casual Detachment recruitment, with a request for 2,830 officers and enlisted men to volunteer for “a dangerous and hazardous mission.” [39]

The request was promptly disseminated across the U.S. Army. Ogburn writes:

“At important commands all across the country and at posts in the Caribbean, the directive from Washington had been read aloud at formations, including the specific statement that what volunteers were wanted for was a ‘dangerous and hazardous mission.’ It also had been read to the troops in the South and Southwest Pacific.”[40]

Before long, the men who would make up Merrill’s Marauders were on their way to their ports of embarkation.

In a progress report dated 18 September 1943, penned by General Thomas Troy Handy, an update on the 1688th Casual Detachment (Galahad) read as follows:

- The following personnel for American Long-Range Penetration Units for employment in Burma are being satisfactorily assembled at the San Francisco Port of Embarkation:

960 jungle-trained officers and men from the Caribbean Defense Command.

970 jungle-trained officers and men from the Army Grand Force.

- A total of 674 battle-tested jungle troops from the South Pacific are being assembled at Noumea (the capital city of New Caledonia) and will be ready for embarkation on the Lurline on 1st October.

- General MacArthur was directed to furnish 274 battle-tested troops. He was able to secure only 55 volunteers from trained combat troops that had not been battle-tested. These troops will be picked up by the Lurline at Brisbane.[41]

The men furnished by the Army made up three battalions, and it was not long before the entire force was consolidated in Bombay. The unit, now officially designated the 5307th Composite Unit (Provisional), was routed to Deolali, only to be moved to a training camp in Deogarh, where organization and training began in earnest.[42]

The three battalions, on the advice of Brigadier Wingate, were broken down into two standalone groups per battalion. The British term was column; however, American leadership—intent on placing their own flair on the unit—designated them combat teams. Mortimer explains:

“Each of the six combat teams was color-coded and each trained to operate as a self-contained unit, comprising a heavy weapons platoon, a rifle company, an intelligence and reconnaissance (I&R) platoon, a communications platoon, and a pioneer and demolitions detachment.”[43]

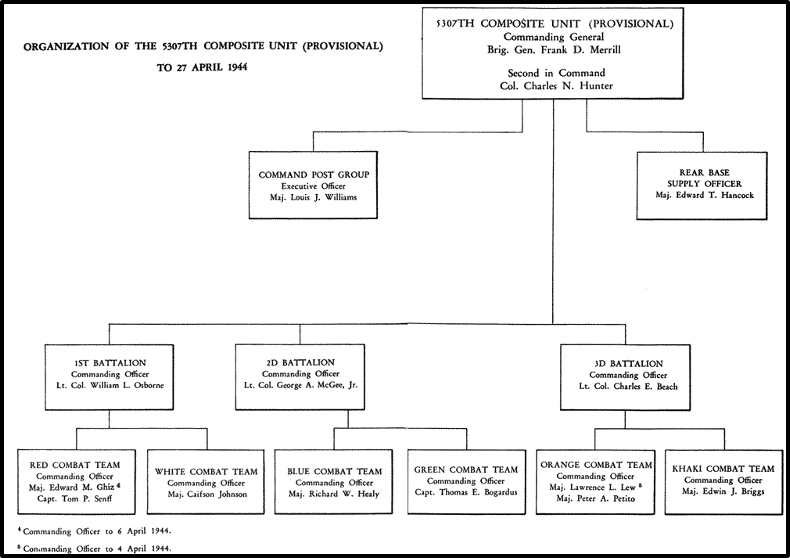

The organization of each battalion is shown in Figure 2.

First Battalion and its Red and White combat teams were placed under the command of Lieutenant Colonel William Osborne, with each combat team falling under Major Edward Ghiz and Major Caifson Johnson, respectively. The Second Battalion, led by Lieutenant Colonel George Alexander McGee, consisted of the Blue combat team commanded by Major Richard Healy and the Green combat team commanded by Captain Thomas Bogardus. Finally, the Orange and Khaki combat teams, under Major Lawrence Lew and Major Edwin Briggs respectively, made up the Third Battalion with Lieutenant Colonel Charles Beach as commanding officer.[44]

The Command chart is shown in Figure 3.

| Battalion Headquarters | Combat teams | Total | ||

| No. 1 | No. 2 | |||

| Officers | 3 | 16 | 16 | 35 |

| Enlisted men | 13 | 456 | 459 | 928 |

| Aggregate | 16 | 472 | 475 | 963 |

| Animals (horses and mules) | 3 | 68 | 68 | 139 |

| Carbines | 6 | 86 | 89 | 181 |

| Machine guns, Heavy | 3 | 4 | 7 | |

| Machine guns, Light | 2 | 4 | 6 | |

| Machine guns, Sub | 2 | 52 | 48 | 102 |

| Mortars, 60-mm | 4 | 6 | 10 | |

| Mortars, 81-mm | 4 | 3 | 7 | |

| Pistols | 2 | 2 | 4 | |

| Rifles, Browning Automatic | 27 | 27 | 54 | |

| Rifles, M-1 | 8 | 306 | 310 | 624 |

| Rockets | 3 | 3 | 6 | |

Note: This table does not include the supply base detachment at Dinjan.

Figure 2. Organization of Battalions, Merrill’s Marauders, February-May 1944. Source: U.S. Army Center of Military History, Washington, D.C., United States Army, 1990

Battalion commanders were given the reins in training their respective personnel and encouraged to make the training program provided by higher authorities their own. Just over two months were dedicated to the training of Galahad. Physical fitness was an integral part of the regimen, as the dense jungle and unforgiving terrain of northern Burma would undoubtedly take its toll on the men of the 5307th. Individual skills, platoon tactics, and company-, combat team–, and unit-level exercises were developed and conducted.[45] The bulk of the two months, however, was focused on creating cohesive and efficient units at the squad and platoon levels.[46]

Figure 3. Organization of the 5307th Composite Unit (Provisional). Source: U.S. Army Center of Military History

Aside from battalion training directed organically by the U.S. Army, the men of the 5307th participated in several training operations under the tutelage of Brigadier Wingate and his Chindits, who were also preparing for another penetration mission into Burma.[47] On one occasion, the training operation—a force-on-force event tasking the Chindits with infiltrating and securing an airfield held by men of the 5307th—was concluded early when physical fights between members of each force threatened to determine the outcome of the maneuver.[48]

The joint training, despite spirited rivalries, was nonetheless valuable in preparing Merrill’s Marauders. The U.S. Army’s records explain, “Ten days spent on maneuvers with General Wingate’s troops brought to light minor deficiencies. There was a shortage of pack animals, and the changes that had been made in organization and equipment required final adjustment.”[49] Adjustments would be made quickly, as Galahad would soon be marching into Burma.

Proof of Concept

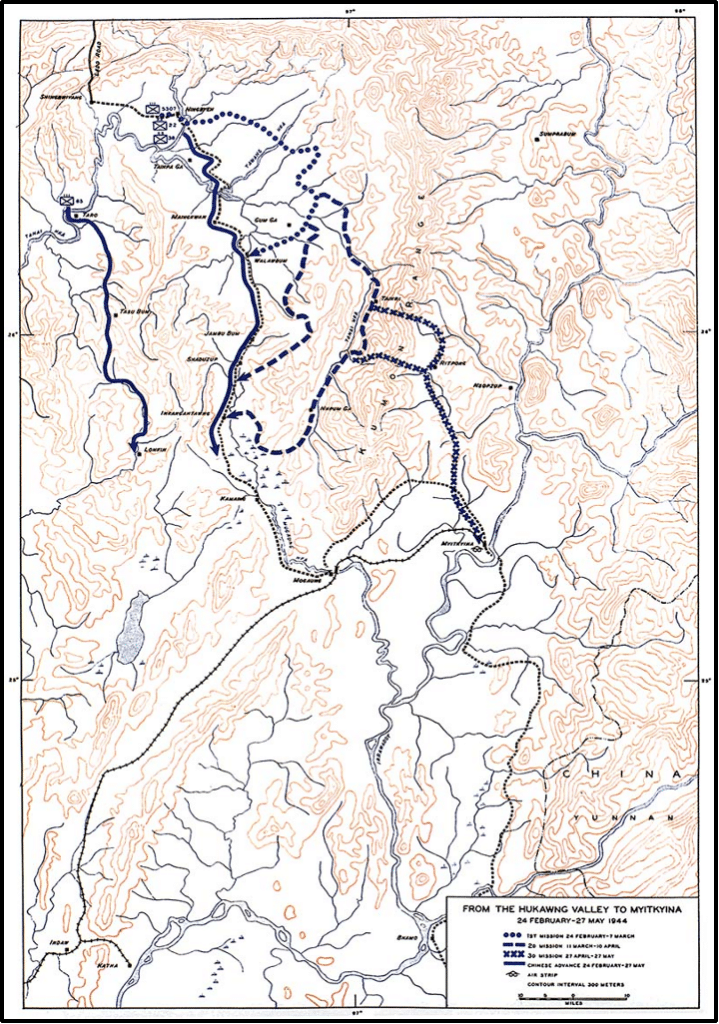

At 2200 hours on 7 February 1944, Task Force Galahad began its 140-mile march along the 40-foot-wide Ledo Road into northern Burma.[50] Firmly under the command of General Stilwell, the 5307th was headed into enemy territory, tasked with providing long-range penetration support to the Chinese 22nd and 38th Divisions, who at the time were advancing southward through the Hukawng Valley toward the Japanese 18th Division. The 18th was a force of about 7,000 men and occupied fortified defensive positions along the Kamaing Road, effectively controlling the only motor supply route in the area.[51]

General Stilwell envisioned the men of the 5307th conducting wide, footborne flanking maneuvers through the jungle in coordination with a Chinese frontal assault to dislodge Japanese forces. All three battalions were assigned to the task and stepped off to the east by dawn on 3 March. To reach their objective of emerging at the rear of the Japanese forces and cutting the Kamaing Road, the Marauders took a wide, sweeping route to the enemy’s right flank.[52] Each of the three battalions followed a different parallel trail that guided them south toward Walawbum.[53]

The men of the 5307th were able to infiltrate the Japanese rear echelon relatively undetected. Their presence was not known to the Japanese until they were some 20 miles behind enemy lines; prior to discovery, the Marauders had encountered only small enemy patrols and parties.[54] Once discovered, the men of Galahad engaged in numerous hard-fought battles until 5 March, when—after one final failed effort to dislodge the American forces—the Japanese withdrew to the south across the Nambyu River.[55]

By 9 March, the Marauders and the combined Chinese forces had converged on Walawbum and cleared the town of Japanese combatants. The Marauders’ first operation was a resounding success and a confirmation of the long-range penetration unit’s proof of concept. U.S. Army historians recount:

“In 5 days, from jump-off on 3 March to the fall of Walawbum on 7 March, the Americans had killed 800 of the enemy, had cooperated with the Chinese to force a major Japanese withdrawal, and had paved the way for further Allied progress. This was accomplished at the cost to the Marauders of 8 men killed and 37 wounded … [sickness further affected the 5307th numbers]. Of the 2,750 men who started toward Walawbum, about 2,500 remained to carry on.”[56]

Battle-tested and successful in their first act against the enemy, Merrill’s Marauders were viewed as a viable tactical and operational force that could be used in conjunction with traditional troops to expel the Japanese from Burma. The proof lay in the results—and the men of the 5307th would face exponentially more hardship as their campaign across northern Burma continued southward.

Operational Success

The Marauders’ victory at Walawbum provided General Stilwell with control of the Hukawng Valley—an operational success that opened supply lines for the Allied forces while driving the Japanese further south into the Mogaung Valley, just below the town of Shaduzup. The coordinated effort between the 5307th and the Chinese main force had worked. General Stilwell’s strategy was showing promise.

Pleased with the results of the Marauders’ jungle-penetrating capabilities, General Stilwell wanted to keep the Japanese on the back foot. He instructed the men of the 5307th to conduct another wide flanking maneuver in concert with a direct push south by the Chinese. Gavin Mortimer explains:

“Stilwell’s plan was for the Chinese 22nd Division to spearhead the advance south along the Kamaing Road toward Jambu Bum, while to the west, the Chinese 65th Regiment covered the right flank. The Marauders’ task was another encircling operation, swinging east of the Kamaing Road and penetrating through the jungle to the Japanese rear, where they would cut supply lines, disable communications, and sow confusion in the enemy’s ranks.”[57]

The 1st Battalion of the 5307th was to march due south over the Jambu Bum mountain, with the Chinese 113th Infantry Regiment in tow to aid in deconfliction, and then cut west to encircle the enemy at Shaduzup. The 2nd and 3rd Battalions were instructed to parallel the 1st and penetrate further south to set up blocking positions on the road between Shaduzup and Kamaing.[58] The actual scheme of maneuver is shown in Figure 4.

Movement south was initiated on the morning of 12 March. It took the 1st Battalion until 21 March to get within five miles of Shaduzup. The march was slowed by dense jungle and periodic engagements with Japanese forces. The assault force was forced to call in air resupply twice en route to its attack point. These resupply runs—a relatively new concept that enabled the Marauders’ deep penetration mission—went without issue.[59]

The 2nd and 3rd Battalions were tasked with setting up a roadblock about 15 miles south of Shaduzup, near the town of Inkangahtawg.[60] The terrain, Japanese resistance, and unexpected enemy reinforcements from the south disrupted the 5307th’s timing and forced the 2nd and 3rd Battalions into a phased withdrawal from the area. The force fell back to high ground at Nhpum Ga, with the 2nd Battalion taking up a defensive position there and the 3rd securing the airstrip at Hsanshingyang, a few miles north.[61]

From 28 March until the 1st and 3rd Battalions were able to break through the enveloping Japanese forces on 8 April, the 2nd Battalion fought for their lives at Nhpum Ga.[62] Japanese reinforcements had encircled the 2nd Battalion and made continuous efforts to overrun its perimeter. By the end of the combat at Nhpum Ga, Army reports state:

“The total number of Marauder casualties … was 57 killed and 302 wounded. The number evacuated to hospitals by air because of wounds or illness caused by amoebic dysentery and malaria reached a total of 379. The figure of known enemy dead exceeded 400.”[63]

Merrill’s Marauders, though unable to achieve their original objective from early March, had significantly weakened Japanese resolve in Burma. Despite suffering substantial casualties, they succeeded in pushing Japanese forces further south, paving the way to their final and most important target—the airfield at Myitkyina.

Despite the condition of the Marauders and their belief that rest and reorganization were needed, it was not to be. Myitkyina had to be taken before the monsoon season arrived. Gary Bjorge explains the urgency:

“Higher authorities wanted Myitkyina taken … developments within the coalition at the strategic/political and operational levels were putting pressure on Stilwell to act. Since the tactical situation and the nature of the forces under his command meant that Myitkyina could only be reached and attacked by a task force led by the 5307th, the die was cast…The pressure that Stilwell was feeling from the coalition partners to take Myitkyina was a result of new British and Chinese support for his north Burma campaign. Because the support was, in large measure, a response to American pressure, he knew he could not slacken his efforts.”[64]

As such, the men of the 5307th were mobilized towards that end.

On 30 April, with less than a week to recover from the ordeal at Nhpum Ga, the men of the 5307th struck out toward Myitkyina. Once again, rough terrain and rampant sickness whittled away at the Marauders’ resolve. They continued on, driven by the hope that this would be their final mission. On 17 May, the task force attacked and captured the Myitkyina airfield. The airfield and town quickly fell under siege by Japanese forces, dispelling any hope for a well-deserved furlough for the men of Merrill’s Marauders.

Bjorge describes their condition:

“By the end of May, the 2nd Battalion, which started for Myitkyina with 27 officers and 57 men, had only 12 men left in action. The situation in the 3rd Battalion was about the same. Only the 1st Battalion still had some strength—a handful of officers and 200 men. In his diary entry for 30 May, Stilwell was forced to write, ‘GALAHAD is just shot.”[65]

The men held out, and with 2,500 reinforcement troops—known as the “new Galahad”—the 5307th was able to hold their ground and ultimately take Myitkyina for good. Gary Bjorge sums up the end of the 5307th:

“In the campaign to reach and take Myitkyina, they had reached the limit of what they could do, and they could do no more. There, at the strategic objective, the unit and the soldiers in both came to the end of the line.”[66]

The 5307th had achieved a string of operational successes culminating in the completion of its original strategic aim—but it had cost them dearly.

Strategic Success in Burma

The 5307th Composite Unit (Provisional) was deactivated on 10 August, one week after the capture of Myitkyina. The men of Galahad dispersed just as they had been assembled—no fanfare, not even a final formation.[67] The unit did, however, receive a Distinguished Unit Citation from the War Department. It reads:

“After a series of successful engagements in the Hukawng and Mogaung Valleys of North Burma in March and April 1944, the unit was called on to lead a march over jungle trails through extremely difficult mountain terrain against stubborn resistance in a surprise attack on Myitkyina. The unit proved equal to its task and, after a brilliant operation of 17 May 1944, seized the airfield at Myitkyina, an objective of great tactical importance in the campaign, and assisted in the capture of the town of Myitkyina on 3 August 1944.”[68]

The citation highlights the strategic success of the unit, for it was the retaking of North Burma—to open both land and air supply routes into China, requiring the capture of Myitkyina—that the 5307th was initially created.

Figure 4. Map from the Hukawng Valley to Myitkyina from 24 February to 27 May 1944. Source: U.S. Army Center of Military History, https://history.army.mil/books/wwii/marauders/marauders-covermap.JPG

Gary Bjorge concludes:

“Based on QUADRANT decisions, the CCS [Chiefs of Staff] gave SEAC [Southeast Asian Command] two objectives. One way to carry out operations, ‘for the capture of Upper Burma to improve the air route and establish overland communications with China.’ The other was, ‘to continue to build up and increase the air routes and air supplies of China, and the development of air facilities with a view to a) keeping China in the war, b) intensifying operations against the Japanese, c) maintaining increased U.S. and Chinese air forces in China, and d) equipping Chinese ground forces.’ To achieve these two objectives, the capture of Myitkyina was deemed essential.”[69]

The men of Merrill’s Marauders, with the help of Chinese forces, did just that. The airfield and town of Myitkyina were captured. The Japanese were forced out of “Upper Burma,” and air and land routes were secured and improved upon. For all intents and purposes, the men of the 5307th had accomplished the strategic goals for which the unit had been created.

Tragically, the strategic aims put in place by Allied leadership had changed by the time the Marauders secured their objectives. Webster recounts that, by the fall of Myitkyina:

“The Allied chiefs had opted to attack Japan from the Pacific islands and not from China. This line of thinking made the fight to ‘keep China in the war’ almost pointless. The war on Japan would now be fought from the sky, by planes off Pacific Ocean islands … Despite the sweat and toil of creating the Ledo-Burma road, despite the blood spilled on the soil of Burma, India, and China to support the road, the Burma road had become obsolete even as it was being opened. The war had evolved past an overland supply route from India to China.”[70]

Merrill’s Marauders had faced stiff enemy resistance, dense and unforgiving mountainous jungle terrain, and a plethora of diseases in their efforts to secure strategic success in the CBI. Their sacrifice and stalwart actions cannot be disputed. Strategically, the utilization of this special operations force was a victory for the Allied forces. The strategy, however, was abandoned in favor of a new one—leaving the triumph of the 5307th Composite Unit (Provisional) as hollow as the remaining men of Galahad who staggered across the finish line General Stilwell had laid for them.

Conclusion

The conception, creation, staffing, training, and utilization of the 5307th Composite Unit (Provisional) were spurred by a strategic requirement in the CBI theater. The Allied leadership, although at odds regarding the importance of China in the fight against Japan, required a special operations force capable of penetrating deep behind enemy lines in Burma and uprooting Axis power there.

Faced with the projection of an 80 percent casualty rate, rugged terrain, torturous conditions, and a determined enemy, the men recruited for the 5307th fought on toward their objective. Merrill’s Marauders fought in three major battles and a multitude of smaller engagements on their way to capturing the airfield at Myitkyina and forcing the Japanese out of northern Burma. Their efforts, at the time, were seen as vital to the strategic aims of the Allies. China’s vast untapped potential and its geographic advantage as a staging point for future attacks against mainland Japan made it, in the eyes of Allied leadership, impossible to lose.

Had the strategic situation not changed by the time Task Force Galahad reached its objectives, the efforts of Merrill’s Marauders might have secured a place in history as one of the most instrumental efforts of the Pacific theater. Unfortunately for the men of the 5307th, the strategic landscape did change. China’s perceived primacy as a foothold against Japanese imperialists fell second to the Pacific islands, and with that shift, the strategic successes of the Marauders were eclipsed.

The sacrifice and hard-won battles of Merrill’s Marauders, however, live on in the lineage of the 75th Ranger Regiment. The Regimental Flash, worn prominently on every Ranger’s tan beret, displays the colors of each of the 5307th combat teams. The regiment’s Distinctive Unit Insignia is the very same—although slightly modified—design as that of the unit patch worn by Merrill’s Marauders.

For the 75th Ranger Regiment, the legacy of the 5307th is deeper than just metal on a duty uniform. The history of the regiment is a long and colorful one, and the exploits of Merrill’s Marauders are among the most prominent. The men of the 5307th laid the foundation for special operations forces like the 75th Ranger Regiment and will always be remembered for their daring, dedication, resolve, and courage under fire. Their strategic success cannot be doubted. If only the strategy they fought so hard to secure had remained in place, there would be no question as to their efficacy.

[1] Donovan Webster, The Burma Road: The Epic Story of the China-Burma-India Theater in World War II (New York: Perennial, 2004), 25.

[2] Webster, The Burma Road, 25.

[3] Gerald Astor, The Jungle War: Mavericks, Marauders, and Madmen in the China-Burma-

India Theater of World War II (Hoboken, NJ: J. Wiley & Sons, 2004), 5.

[4] Webster, The Burma Road, 25.

[5] Gavin Mortimer, Merrill’s Marauders: The Untold Story of Unit Galahad and the Toughest

Special Forces Mission of World War II (Osceola: Quarto Publishing Group USA,

2013), 3.

[6] Mortimer, Merrill’s Marauders, 4.

[7] Webster, The Burma Road, 29.

[8] Gary J. Bjorge, Merrill’s Marauders: Combined Operations in Northern Burma in 1944 (Fort

Leavenworth, Kansas: Combat Studies Institute, U.S. Army Command and General Staff College, 1996), 4.

[9] Bjorge, Merrill’s Marauders, 5.

[10] Jon Diamond, Stilwell and the Chindits: The Allies Campaign in Northern Burma, 1943–

1944 (Havertown: Pen & Sword Books, 2014), 59.

[11] Bjorge, Merrill’s Marauders, 4.

[12] Astor, The Jungle War, 8.

[13] Charles Romanus and Riley Sunderland, Stilwell’s Command Problems. (Washington, D.C.: Office of the Chief of Military History, United States Army, 1953), 353.

[14] Bjorge, Merrill’s Marauders, 4.

[15] William T. Y’Blood, Air Commandos Against Japan: Allied Special Operations in World

War II Burma (Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 2014), VII.

[16] Astor, The Jungle War, 145-146.

[17] Astor, The Jungle War, 146.

[18] Bjorge, Merrill’s Marauders, 5.

[19] Bjorge, Merrill’s Marauders, 5.

[20] Bjorge, Merrill’s Marauders, 1.

[21] Merrill’s Marauders, February-May 1944 (Washington, D.C.: Center of Military History,

United States Army, 1990), 8.

[22] Astor, The Jungle War, 156.

[23] Joint History Office (U.S.), The Quadrant Conference: August 1943, (Washington, D. C.:

United States Government Printing Office, 2017), 427-428.

[24] Astor, The Jungle War, 157.

[25] Charlton Ogburn, The Marauders (Woodstock, NY: Overlook Press, 2002), 15.

[26] Patrick K. O’Donnell, Into the Rising Sun: in Their Own Words, World War II’s Pacific

Veterans Reveal the Heart of Combat (New York: Free Press, 2003), 12.

[27] Astor, The Jungle War, 126.

[28] Diamond, Stilwell and the Chindits, 20.

[29] Diamond, Stilwell and the Chindits, 21.

[30] Diamond, Stilwell and the Chindits, 21.

[31] Astor, The Jungle War, 127.

[32] Diamond, Stilwell and the Chindits, 22.

[33] Diamond, Stilwell and the Chindits, 22.

[34] Astor, The Jungle War, 127-130.

[35] Astor, The Jungle War, 130.

[36] Webster, The Burma Road, 94.

[37] Webster, The Burma Road, 106.

[38] Ogburn, The Marauders, 44.

[39] Webster, The Burma Road, 164.

[40] Ogburn, The Marauders, 29.

[41] Mortimer, Merrill’s Marauders, 8-9.

[42] Mortimer, Merrill’s Marauders, 11.

[43] Mortimer, Merrill’s Marauders, 30.

[44] Mortimer, Merrill’s Marauders, 30.

[45] Mortimer, Merrill’s Marauders, 14-15.

[46] Mortimer, Merrill’s Marauders, 15.

[47] Mortimer, Merrill’s Marauders, 32.

[48] Ogburn, The Marauders, 54.

[49] Mortimer, Merrill’s Marauders, 16.

[50] Astor, The Jungle War, 193.

[51] Mortimer, Merrill’s Marauders, 31.

[52] Ogburn, The Marauders, 91.

[53] Webster, The Burma Road, 169.

[54] Mortimer, Merrill’s Marauders, 35.

[55] Mortimer, Merrill’s Marauders, 41.

[56] Mortimer, Merrill’s Marauders, 45.

[57] Mortimer, Merrill’s Marauders, 89.

[58] Astor, The Jungle War, 235.

[59] Mortimer, Merrill’s Marauders, 52-53.

[60] Gary J. Bjorge, Merrill’s Marauders: Combined Operations in Northern Burma in 1944, Army History, no. 34 (1995): 21.

[61] Astor, The Jungle War, 242-244.

[62] Mortimer, Merrill’s Marauders, 87-90.

[63] Mortimer, Merrill’s Marauders, 91.

[64] Bjorge, Merrill’s Marauders, 23.

[65] Bjorge, Merrill’s Marauders, 27.

[66] Bjorge, Merrill’s Marauders, 27.

[67] Ogburn, The Marauders, 282-283.

[68] Ogburn, The Marauders, 283.

[69] Bjorge, Merrill’s Marauders, 15.

[70] Webster, The Burma Road, 326.