As the special operations profession enters a new era of Special Operations Forces (SOF) involvement in geopolitical competition in the “gray zone” as part of a comprehensive U.S. strategy of integrated deterrence, the leadership skills developed by the broader profession of arms remain necessary but insufficient. For special operations, the complexity of the emerging security environment suggests there is increasing uncertainty on how the Joint SOF profession must exercise leadership in support of American interests that center on partner forces of both developed and developing nations, as well as the interests of micro-level populations and associated non-state, sub-state, and paramilitary actors. As SOF adapts to these requirements through joint and combined integration, or “the imperative of approaching complex, complicated, wicked, and compounded challenges through ‘whole of governments, whole of societies,’” SOF must recognize the reality that this environment necessitates a new framework for understanding military leadership.1

Leader development and leadership education in the Joint SOF profession, and to an extent, the profession of arms, is at a historic inflection point. For the Joint SOF profession to produce the necessary leaders needed for the future, SOF must relook and reconsider the leadership education required for leading within the human domain in a world that requires military leaders to become much more than maneuver experts or masters of the interagency (JIIM-C) environment within complex ecosystems and networks. Instead, this inflection point requires operational leaders and senior commanders to lead through networks and lasting relationships within the most complex micro-level environments afforded by the human domain. Professional military education (PME) institutions that traditionally produce America’s great Generals and Admirals must openly challenge all previous assumptions.

Furthermore, the SOF profession must recognize the leadership challenges that have emerged in recent watershed events like 9/11 where SOF (at all levels) stake their survivability and operational success on their ability to offer inspiring leadership within a complex ecosystem rather than the traditional command of the elusive decisive conventional battle. Specifically, Joint SOF professionals must recognize the degree to which micro-level populations in developing countries and tribal societies contribute to America’s strategy of integrated deterrence. Even if America manages to achieve optimal leveraging of all elements of national power to successfully out-compete our great power adversaries through conventional deterrence, the risks to American interests in the “gray zone” remain pervasive. Outside of conventional military dominance, American military forces can defeat our great power adversaries directly and still suffer costly strategic setbacks in the extant strategic spaces between peace and large-scale combat operations (LSCO).

Thus, all military leaders involved in security competition as part of SOF’s support

to 21st century irregular warfare must recognize that modern leadership is about leading much more than joint military formations.2 Instead, modern SOF leaders must offer quality leadership at the micro-level decisive point where integrated competition remains largely unseen on the global stage. Joint SOF leaders at every echelon must leverage relational rather than transactional leadership styles as populations and their associated partner forces determine who wins or loses in strategic competition. In this space, the population chooses a winner based on utilitarian preferences, independent of the more powerful military’s ability to leverage physical force.

To understand the degree to which population-centric conflict requires a new

understanding of more than just leadership within the SOF profession, the “gray zone” challenges inherent to SOF environments are also shaping the traditional sense of military “officership” as well as “generalship” at the strategic level. As more than a strategic consideration for SOF, the “liberator’s dilemma” thought experiment underscores the degree to which military operations in the human domain increasingly rely on support from indigenous populations and associated micro-level partner forces. In short, the liberator’s dilemma provides a necessary pragmatic and ethical explanation for the realities that strong state actors face when engaging in third-party military operations designed to “liberate” an oppressed population from a hostile political regime. Specifically, the liberator’s dilemma serves both a rational choice for maximizing the effect of population-centric insurgency models3 under the “insurgent swims through the population like a fish swims through the sea” idea,4 as well as with responsible and pragmatic ethical consideration for the “liberated” population.

Using rational choice and ethical consideration models as a guide, the liberator’s

dilemma argument does more than expose critical flaws and ethical dilemmas that emerge during liberation operations. Instead, the liberator’s dilemma argument shines a meaningful light on the nature of U.S. military leadership in the era of integrated deterrence, arguing that relational, cross-cultural, and networked leadership theories have taken primacy over

“classic” leadership education traditionally rooted in transactional, “great man,” charismatic, and heroic styles of understanding how state actors and military leaders function in great power competition.5

Gray Zones, Selectorates, and Insurgencies

Effective leadership in complex and “gray zone” environments is impossible without understanding the dynamic and elaborate political and social ecosystems that exist in “classic” population-centric insurgencies. Population-centric insurgency models emphasize that the will or agency of a local population is the primary actor capable of determining success in insurgency-based military operations marked by a strong state actor engaged in competition with a weak counter-state actor. For the strong state, the population is the critical link to overcoming the information disadvantage whereby the state cannot easily or accurately identify members of the insurgency. As such, the population becomes an essential ally capable of identifying rebels for surgical strike kinetic targeting.

For the weaker counter-state, the population is also critical for survival. Insurgents

rely on a supportive population, allowing them to overcome their relative size and power disadvantages compared to the state by providing concealment from state-sponsored security forces. Likewise, when the rebels are protected or hidden by the population, they can attack agents of the state from hidden safe-haven positions and erode the limited resources and support of the state to gain a long-term temporal advantage. In support of this hypothesis, insurgency scholars find that increasing access to operational safe havens empirically increases the length of insurgent conflicts, which erodes state power over time.6

In understanding how regime leaders add to the micro-level political dynamic of

insurgency, Bueno de Mesquita & Smith argue that a government’s first priority, well ahead of caring for the people, is to stay in power.7 Therefore, regime leaders disperse resources to powerful political stakeholders and in-groups (or “selectorates”) using rational calculations balanced by the relative size of powerful actors whose support is required to stay in power, in comparison to the size of the regime’s core.8 In short, governing regimes maximize their likelihood of staying in power by dispersing the spoils of their power to as few people as necessary in order to retain the bulk of their power at the center. As such, closed regimes tend to have smaller selectorates, achieve results with smaller payoffs, and are incentivized to demonstrate more repressive behavior toward their citizens compared to more open and democratic regimes. In autocratic regimes, not only do dictators tend to behave badly toward their populations, autocrats rely on centralized state power and repressive security forces to protect themselves from being punished by the population. However, dictators sometimes become targets of more powerful open regimes (such as the U.S.) through liberating military operations publicly framed in the spirit of de oppresso liber, the motto of U.S. Army Special Forces.

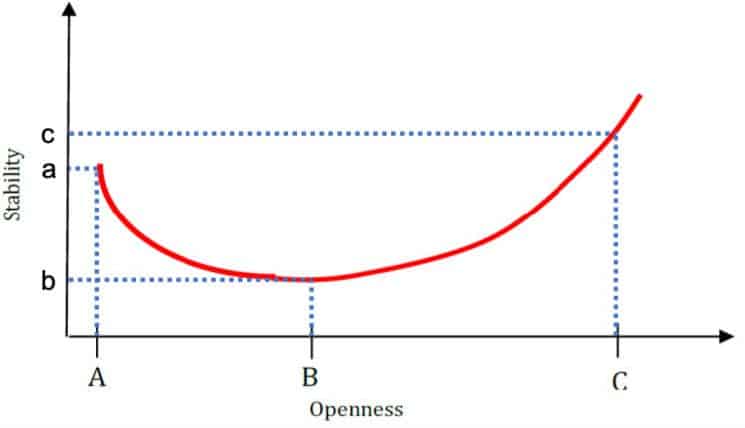

Key to understanding regime preference for stability is the effect that regime type

has on regime survivability and stability. Specifically, Bremmer explains how the

relationship between regime openness and regime stability is often non-linear and

counterintuitive.9 By comparing recognized measures for regime openness, a measurable variable between low and high openness (dictatorship through democracy), with corresponding regime stability, the correlation between openness and stability is found to be curvilinear rather than a straight line.10 Although the most open governments tend to be the most stable, the most closed (autocratic) governments also tend to be highly stable. The effect produces a J-shaped curve that illuminates the problematic nature of replacing certain dictatorships with democracies.11 In this context, military operations aimed at democratizing weaker, closed regimes result in decreased stability for the population, while similar operations against more open regimes tend to enhance or increase stability.

Figure 1 represents the strategic implications of the J curve on an indigenous

population. Democratizing a stable but closed regime at point A by moving it toward greater openness at point B is likely to be destabilizing. The corresponding shift in the Y-axis moves from a stability level at a to a lower stability level at b resulting in an overall, and undesired, reduction in stability. However, shifting a less autocratic regime at point B toward greater openness at point C results in the Y-axis shifting from a stability level of a to a higher stability level of c. This model reaffirms that prescriptive measures for regime overthrow for A-type states is not the same as for B-type states, suggesting that prescriptive measures for American political and military leaders in dealing with these cases is also not the same.

Theoretically, a more powerful and open regime can overthrow a weaker and more

closed regime in order to free its citizens from tyranny. In doing so, the population should remain highly cooperative in assisting the stronger actor in targeting bad actors within the closed regime, while the strong actor, in turn, potentially gains an ally and future trading partner. Unfortunately, the expectations of this model fail to account for the paradoxical and unintended consequences found when observing the liberator’s dilemma thought experiment. Thus, the liberator’s dilemma offers a more complete explanatory lens for understanding why popular support at the onset of liberation eventually leads to support for the incumbent and repressive regime.

When popular support switches sides, the liberating force risks becoming locked

into costly and protracted counterinsurgency operations that resemble costly and long-term occupation. Furthermore, scholars agree that protracted conflicts for militarily superior actors can be a strategic disadvantage when weaker actors defend against strong-state powers using an indirect military approach.12 In such cases, weak actors can deny stronger actors their military advantage in part by incentivizing stronger actors to risk harm to the indigenous population. This advantage is critical for success in population-centric insurgency models.13

The Liberator’s Dilemma

The liberator’s dilemma serves as an informative guide for navigating the leadership challenges inherent to highly complex “gray zone” military operations by showcasing the agency and strategic power within indigenous populations. With micro-level popular support being the key to military success in any version of population-centric warfare, the kind of warfare inherent to strategic competition within a strategy of integrated deterrence, the ability to provide meaningful and effective leadership in this part of the human domain becomes essential. However, the American track record for succeeding at this leadership challenge is replete with strategic failure.

By reframing population-centric military operations as primarily leadership

challenges, modern military leaders and SOF professionals will recognize the need to develop new skills that can be leveraged against the paradox of the liberator’s dilemma so that U.S. forces can compete and win through better partnerships built on relational rather than transactional leadership styles. Although the liberator’s dilemma is resented as a stylized strategic choice model, the variables presented offer opportunities for military leaders to better understand and connect with micro-level partner forces in 21st century irregular warfare. The liberator’s dilemma argument shines a meaningful light on the nature of American leadership in the era of integrated deterrence, arguing that relational, cross-cultural, and networked leadership theories have taken primacy over “classic” leadership education rooted in transactional and “great man” theories in understanding how state actors and military leaders function in great power competition.

T=0

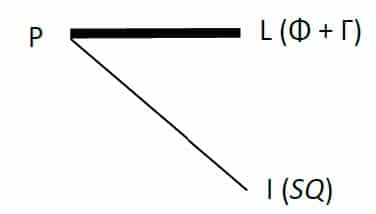

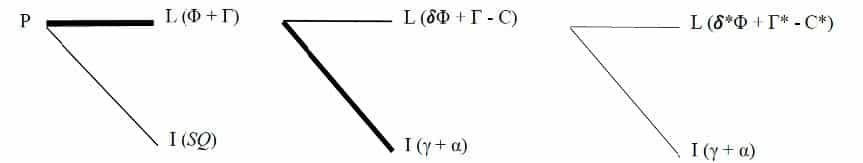

Figure 2. Population Support Decision tree at Time Period 0

The liberator’s dilemma assumes that a third-party intervention force of a strong

state military has achieved a successful initial invasion of a less powerful autocratic regime that challenges the strong state’s interests. The strong state “liberator” offers the population freedom from the repression of the stable but closed adversarial regime. As the stronger actor in the conflict, the liberator also assumes a moral obligation to assume responsibility for any destabilization of the population. However, large-scale stability operations often fall outside of the capabilities or resources available to most liberating powers. When a liberating force fails to provide sufficient stability to the indigenous population, the people are likely to suffer a fate worse than under the prior autocratic regime. Thus, liberating people from authoritarian regimes is a risky gambit fraught with the risk of moral hazard to the population’s welfare, ergo the liberator’s “dilemma.” Although the population might initially welcome the liberating force, competing incumbent groups from within the overthrown regime challenge the authority of the liberating force. The liberator’s dilemma underscores the logic that a stylized strategic choice model uncovers within the micro-level bargaining and rational choice problems found in figure 2.

The leadership challenge inherent to the liberator’s dilemma begins when a stronger, more open regime liberator (L) physically removes a weaker and more closed incumbent regime (I). At this point, the population (P) becomes the center of gravity for producing the expected outcomes of the conflict as predicted by insurgency theory. 14 As figure 2 demonstrates, each side of the conflict offers varying utility for P. At the conclusion of the successful invasion (Time period 0), I can only offer the status quo (SQ), or a reduced version of the status quo, resulting from the tyrannical nature of the recently deposed dictatorial regime. Meanwhile, L offers freedom from oppression (Φ), by virtue of successful regime overthrow, combined with the introduction of goods and services (Γ) that L can now provide for the P. Since the invasion of L was successful over I, the model assumes that (Φ + Γ) reflects an improvement to the SQ, such that the utility of L is greater than the utility of I or (Φ + Γ) > (SQ), indicating that a rational P should initially prefer to support L over I.

However, classic insurgency models are static and fail to account for temporal

considerations and the expectation that a militarily defeated adversary will still compete against the liberator. Likewise, it also follows that “classic” models also fail to consider the impact that leadership, the ability of the liberator to gain and sustain popular support, has on the outcomes of insurgency-based operations. By considering the dynamics of competition within an insurgency-based campaign, military leaders can better anticipate and manage the physical and relational needs of the liberated population.

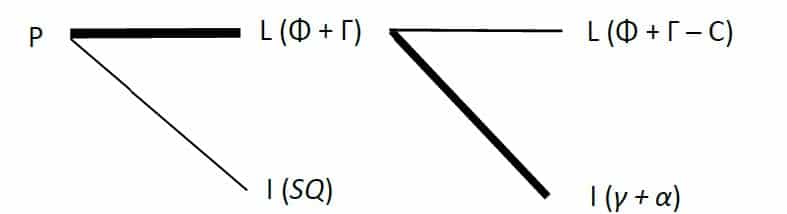

T=0 T=1

In scholarly competition literature, political interaction is considered less a discrete event than a series of repeated interactions between liberating and incumbent actors. In the case of competition between the Catholic and Protestant churches in Latin America, Trejo (2009) noted that the arrival of Protestant missionaries into traditionally Catholic areas in the 1960s-1980s had a negative effect on popular support for the incumbent Catholic Church.15 The value of goods and services provided by the newly introduced Protestant missionaries drew from traditional Catholic congregations.16 Not surprisingly, the Catholic church responded to this competition with increased investment in their own levels of goods and services. At this point, the population recalculated the relative utility offered by the Catholic and Protestant services and shifted support back to the incumbent Catholic Church.17 The theoretical implications for a would-be liberator are similar and the ability for the liberator to understand and positively influence the human domain becomes the key to successful leadership in a population-centric campaign.

At time period 1, I responds to external competition by increasing the utility of their offer to P. After losing to L at time 0 with an offer of SQ, I now also competes with L by offering their own (typically smaller) version of goods and services (γ) as part of their offer. Furthermore, I also benefits from its shared affinity (α) in linguistic and cultural alignment to P, for a total utility equal to γ + α. However, as the quality of I’s offer increases over time, the quality of L’s offer begins to decrease. The initial value of the freedom from the repressive regime (Φ) begins an inevitable decline represented by the discount variable (𝛿), such that [0 > 𝛿 > 1] with the value of 𝛿 eventually reaching 0. Therefore, as long as the conflict

continues, the value of Φ will also eventually reach 0.

Additionally, L offers the same Γ as in time 0 due to the incorrect assumption that P’s support has been secured, while L suffers an additional reduction in utility resulting from the cost of foreign occupation (C), for a total new value of (𝛿 Φ + Γ – C). At this point, P will switch sides and support I if the utility of I becomes greater than the utility of L or:

(γ + α) > (𝛿 Φ + Γ – C)

When this happens, the liberator’s dilemma exposes friction for the previously

dominant L. In contrast to L’s best intentions, P is now worse off at T=1 than it was at T=0, all due to the failure of the liberating force. The result of this dynamic is that the indigenous population remains skeptical of the liberating force, and the liberating force feels betrayed by the population, all while the stability of the population remains in decline. This sense of skepticism and betrayal thus becomes the entirety of the leadership frame required for the liberator to escape from the population trap.

Implications of the Model

The implications for the liberator’s dilemma at this point are critical to understanding the complex leadership challenges inherent to classic population-centric insurgency theory, where the population is key to success.18 In freeing people from a tyrannical dictator, L becomes the change agent that causes instability for the population. At this point, the subsequent reductions in stability indicate that the value of L’s original offer is decreasing. The value of freedom at time period 1 is reducing along with the relative value of Γ, given that I is now offering γ. Furthermore, the costs of occupation (C) are expected to increase over time, while the benefit of affinity (α) simultaneously increases. This means that L becomes responsible for making P paradoxically worse off than before the military intervention while simultaneously improving the quality of governance for I through competition. By exposing harm to the population, the liberator’s dilemma underscores a pragmatic and ethical problem for intervening regimes that must be accounted for when promoting global stability through American leadership through military intervention within a strategy of integrated deterrence.

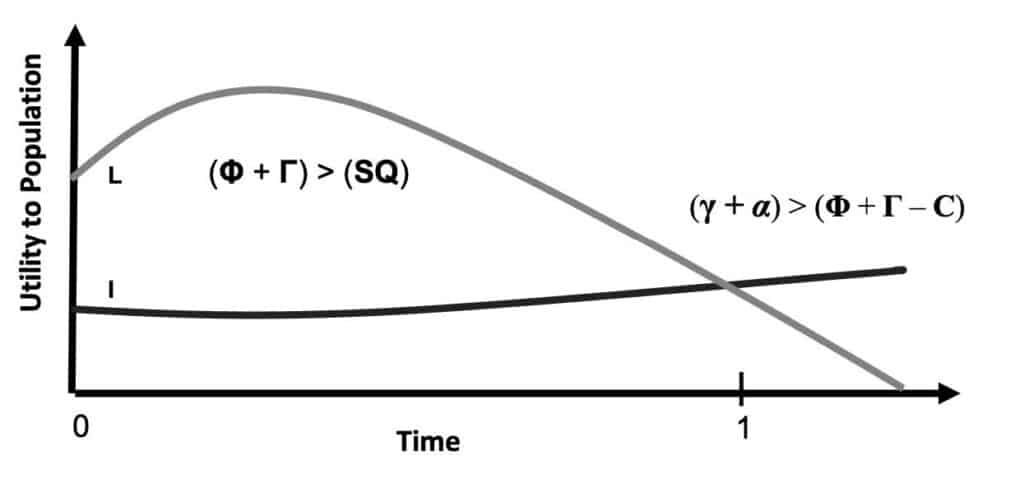

To minimize the negative impact of the liberator’s dilemma on an indigenous

population, an intervening power should capitalize on the opportunity to increase its utility to the population at time 1. At this point, the population has shifted support from the liberator (L) to the incumbent (I) so that the incumbent is in a position to improve its offer and regain popular support. It is also critical that the liberator not only gain popular support but pursue operations that promote long-term sustainability and prevent negative impacts on popular support. To do this, the liberator must understand how time impacts utility in order to ensure that L > I remains true at time 2 and beyond. Figure 5 illustrates the variables affecting P’s choice. Setting the conditions for L > I means setting the conditions so that (𝛿*Φ + Γ* -C*) > (γ + α) remains true.

T=0 T=1 T=2

Solving for the variables that the liberator is capable of controlling (𝛿*, Γ*, and C*),

the model suggests that the paradox of the liberator’s dilemma is less related to military strength than to the ability of the liberator to exercise relational leadership through building and sustaining meaningful connectedness with a distinct and complex indigenous population. Through the lens of the liberator’s dilemma, the liberator now recognizes the inevitable decline of freedom from oppression (Φ) after regime overthrow, especially given the tendency for the costs of occupation (C) to increase rather than decrease over time. To minimize this tendency, L must ensure that transactional interactions with the population are as low cost as possible while also not relying on the assumption that Φ is sufficient to promote cooperation. From a Maslovian perspective, once the population benefits from Φ, their needs mature as L assumes responsibility for the security of the population following the successful invasion.19 Therefore, value of security is lower at time 2 than it was at time 1, confirming that the value of Φ tends toward decline.

Secondly, the value of Γ must likewise increase in relation to the expected value of

I’s capability to provide γ. Just as businesses in free markets must always improve the value of their services to their customers, so too must liberating forces ensure that their military efforts remain focused on continuously increasing the welfare and stability of the population. If the liberating force is successful in the application of relational and cross-cultural leadership necessary for sustaining connectedness, the population will remain supportive. If not, the liberator will suffer the choice of a rational actor who picks the strategic choice with the greatest utility. Furthermore, the values of Γ vice γ suggest that the population’s behavior is the only useful measurement of success. A liberating force must counter the tendency to create convenient but irrelevant metrics.

Lastly, the liberator must understand the negative effect that an occupying power,

regardless of how seemingly benevolent, comes with increasing costs. The visual effect of seeing armed foreign fighters patrol through population centers and enforcing restrictive population control measures, such as roadblocks and checkpoints, comes with an eventual negative impact on a population. The combined effect of all three variables suggests that static models are bound to fail and that the incumbent will eventually gain support when the liberator fails to account for temporal changes.

Therefore, the liberator’s dilemma model not only underscores the dynamic political interaction between actors involved in insurgency operations, the rational choice nature of the model also illuminates multiple flawed assumptions and subsequent and common suboptimal behaviors that are absent from “classic” insurgency theory. By capturing the temporal and pragmatic nature of liberation operations, considerable leadership adjustments can help reduce the negative effects of this paradoxical dilemma. The application of carefully applied relational leadership through influence rather than military action becomes a force multiplier that allows the liberator to find success by escaping from the trap that befalls an unconnected indigenous population.

Implications for Military Leadership and the Joint SOF Profession

Again, the liberator’s dilemma reminds SOF leaders across the joint SOF profession that U.S. strategic interests and SOF’s role in integrated deterrence can be shaped by the effective use of irregular warfare. However, this realization must account for the function of the liberator’s dilemma that exposes a critical and paradoxical false assumption about population-centric warfare and about the leadership skills required of the Joint SOF profession and of senior military leaders. Furthermore, variables that represent military strength remain

conspicuously absent as the liberator’s dilemma reminds us that “gray zone” operations are foremost leadership problems that require innovative ways of understanding the human domain more than they are measures of military power. In the liberator’s dilemma, force does not equate to power, and recent U.S. military conflicts provide examples where military power without an effective leadership strategy oriented in the human domain leads to protracted conflict and eventual failure. The solution then is to look toward improving our leadership skills before exploring more innovative ways to inflict physical force.

More problematically, traditional professional military education reinforces

leadership models that evolved from a long history of military conquest where conquering military forces enjoy ownership over their historical narratives. 20 However, the military operations most conducive to “gray zone” competition require that military leaders and SOF professionals understand newer and more relational theories on leadership. In irregular warfare, leaders from the tactical special operations team to strategic and political levels must understand how to build connectedness and sustain relationships across highly complex networks and ecosystems. Building and sustaining lasting connectedness in indigenous populations requires that SOF leaders learn to lead differently.

As the liberator’s dilemma exposes, classic counterinsurgency theory fails to

account for certain variables that represent the agency of a partner-force population. Population-centric military operations of all types must recognize and minimize the liberator’s dilemma paradox and consider how to offer utilitarian value to the populations where the U.S. military and SOF professionals operate. Sadly, the impact on the population has been largely a case of failure in our recent conflicts in Afghanistan and Iraq. In observing and comparing urban Afghanistan populations in 2004 and 2011, lasting improvements to stability and quality of life were non-existent. The temporal effects in Afghanistan suggest that the population’s eventual support of the Taliban was less a victory for the Taliban than it was a strategic leadership failure of the military in general and the SOF profession more specifically. We must quickly realize our moral obligation to offer quality leadership to all of the actors within our networks, but most especially to the members of the population whom we often negatively impact.

For liberating operations of the future, as part of a strategy of integrated deterrence and strategic competition, the liberator’s dilemma exposes several important strategic considerations. First, we must begin population-centric military operations with a population-centric end state in mind. This requires consideration for the strategic benefit of limiting force structure ex-ante to a very small footprint in an upfront effort to minimize the inevitable adverse effects that will result from costs of occupation. Likewise, military planners must also dictate long-term objectives that consider the inevitable decline of the initial offering of freedom while considering the strategic effect that goods and services will have on how U.S. forces are perceived by a population over time.

Similarly, leading populations and their associated micro-level partner forces require that both senior military leaders and SOF professionals rigidly enforce stylistic relational leadership continuity across rotational units. The negative impact on the population of “20 one-year wars” versus “one 20-year war” must not continue. Furthermore, promoting effective leadership of an occupied indigenous population and their associated partner forces necessitate that the people perpetually remain the main effort. American forces at all levels must resist the temptation to become enemy-focused and recognize that enemy-centric behavior translated to increasing (not decreasing) the cost of foreign occupation. In doing so, we must also acknowledge that time does not favor the liberator. We must achieve our strategic goals in a manner that promotes sustainability while also reversing entropy as quickly as possible. When population support shifts, we must resist the urge to seek kinetic solutions or to launch personnel surges. These will yield tactical success attached to strategic setbacks. Instead, we must recognize shifts in popular support as reminders that we need to redouble our partner-force and population leadership efforts.

Lastly, we must never forget that liberating military operations come with a moral

hazard when they result in greater harm to the population than the initial status quo. The United States cannot pursue a strategy of integrated deterrence rooted in strategic competition if our cure remains worse than the disease. We must never forget to look at the operation through the lens of the population. Effective and authentic partner-force leadership offers more pragmatic and utilitarian options for the liberated people we wish to help. If military and SOF leaders understand the key tenants of irregular warfare, the liberator’s dilemma should reinforce that irregular warfare is about “people, not platforms” and as such, require that the U.S. military build and sustain a “global capability and capacity” through “patient, persistent, and culturally savvy people who can build the long-term relationships essential to executing IW.”21 In the execution of irregular warfare, if we think we are doing the right thing and the population shifts sides, then we are no longer doing the right thing. Senior leaders and Joint SOF professionals must think like relational networked leaders and leave traditional military leadership solutions for appropriate conventional contexts. As arguably the strongest state actor in history, we must remember that our great power adversaries are always watching and learning. We cannot fail to lead and fall behind.

Endnotes

1 Isaiah Wilson, III and C Anthony Pfaff, “Making the Case for a Joint Special Operations Profession,” Joint Forces Quarterly 105 (Spring 2022): 45.

2 Wilson and Pfaff, “Making the Case for a Joint Special Operations Profession,” 52.

3 David Galula, Counterinsurgency Warfare: Theory and Practice, (London: Frederick A. Praeger,1964); Robert Taber, The War of the Flea: Guerilla Warfare Theory and Practice (London: Granada Publishing Limited, 1965); Mao Tse-Tung, On Guerilla Warfare (Champaign, IL: First Illinois Paperback, 2000a).

4 Mao Tse-Tung, “On Guerilla Warfare.”

5 Thomas Carlyle, Heroes and Hero Worship (Union School Furnishing Company, 1908). http://ebooks.rahnuma.org/religion/Seerat_Taiba/On-Heroes-Worship-And-the-Heroic-in-History.pdf; Thomas Carlyle, On Heroes, Hero-Worship, and the Heroic in History (Univ of California Press, Vol 1); B. A. Spector, “Carlyle, Freud, and the Great Man Theory More Fully Considered,” Leadership 12 (2): 250–60, https://doi.org/10.1177/1742715015571392; Gordon A.Wyner, “The ‘Great Man’ Theory,” Marketing Management (January/February 2009): 6–8.

6 Navin A. Bapat, “The Internationalization of Terrorist Campaigns,” Conflict Management and Peace Science 24, no. 4 (2009): 265–80; Navin A. Bapat, “The Escalation of Terrorism: Microlevel Violence and Interstate Conflict,” International Interactions 40, no. 4 (2014): 568–78. https://doi.org/10.1080/03050629.2014.902818; Idean Salehyan, “Transnational Rebels: Neighboring States as Sanctuary for Rebel Groups,” World Politics 59, no. 2(2007): 217–42; Idean Salehyan, “No Shelter Here: Rebel Sanctuaries and International Conflict,” The Journal of Politics 70, no. 1 (2008b): 54–66; Idean Salehyan, “The Externalities of Civil Strife: Refugees as a Source of International Conflict,” American Journal of Political Science 52, no. 4 (2008b): 787–801; Idean Salehyan and Kristian Skrede Gleditsch, “Refugees and the Spread of Civil War,” International Organization 60, no. 2 (2006): 335–66.

7 Bruce Bueno de Mesquita and Alastair Smith, “Leader Survival, Revolutions, and the Nature of Government Finance,” American Journal of Political Science 54, no. 4 (2006): 936–50. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5907.2010.00463.x; Bruce Bueno de Mesquita and Alastair Smith, The Dictator’s Handbook: Why Bad Behavior Is Almost Always Good Politics. New York, NY: PublicAffairs, 2011).

8 Bruce Bueno de Mesquita and Alastair Smith, “Leader Survival, Revolutions, and the Nature of Government Finance,” American Journal of Political Science 54, no. 4 (2006): 936–50. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5907.2010.00463.x; Bruce Bueno de Mesquita and Alastair Smith, The Dictator’s Handbook: Why Bad Behavior Is Almost Always Good Politics. New York, NY: PublicAffairs, 2011).

9 Ian Bremmer, The J Curve: A New Way to Understand Why Nations Rise and Fall (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2006): 6.

10 Bremmer, The J Curve.

11 Bremmer, The J Curve.

12 Ivan Arreguin-Toft, “How the Weak Win Wars: A Theory of Asymmetric Conflict,” International Security 26, no. 1 (2001): 93–128.; Andrew Mack, “Why Big Nations Lose Small Wars: The Politics of Asymmetric Conflict,” World Politics 27, no. 2 (1973): 175–200.

13 David Galula, Counterinsurgency Warfare: Theory and Practice (London: Frederick A. Praeger, 1964); Robert Taber, The War of the Flea: Guerilla Warfare Theory and Practice (London: Granada Publishing Limited, 1965); Mao Tse-Tung. On Guerilla Warfare (Champaign, IL: First Illinois Paperback, 2000a).

14 Ivan Arreguin-Toft, “How the Weak Win Wars: A Theory of Asymmetric Conflict,” International Security 26, no. 1 (2001): 93–128; David Galula, Counterinsurgency Warfare: Theory and Practice, (London: Frederick A. Praeger, 1964). Andrew Mack, “Why Big Nations Lose Small Wars: The Politics of Asymmetric Conflict,” World Politics 27, no. 2(1973): 175–200; Robert Taber, The War of the Flea: Guerilla Warfare Theory and Practice (London: Granada Publishing Limited, 1965); Mao Tse-Tung. On Guerilla Warfare (Champaign, IL: First Illinois Paperback, 2000a).

15 Guillermo Trejo, “Religious Competition and Ethnic Mobilization in Latin America: Why the Catholic Church Promotes Indigenous Movements in Mexico,” American Political Science Review103, no. 3 (2009): 323–42.

16 Trejo, “Religious Competition 323–42.

17 Trejo, “Religious Competition 323–42.

18 David Galula, Counterinsurgency Warfare: Theory and Practice (London: Frederick A. Praeger, 1964); Robert Taber, The War of the Flea: Guerilla Warfare Theory and Practice (London: Granada Publishing Limited, 1965); Mao Tse-Tung. On Guerilla Warfare (Champaign, IL: First Illinois Paperback, 2000a).

19 Abraham H. Maslow, “A Theory of Human Motivation,” Psychological Review 50 (1943): 370–96.

20 Keith Grint, “A History of Leadership,” in The SAGE Handbook of Leadership, edited by Alan Bryman, David Collinson, Keith Grint, Brad Jackson, and Mary Uhl-Bien, 3–28 (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2011).

21 Joint Operating Concept, 2007.