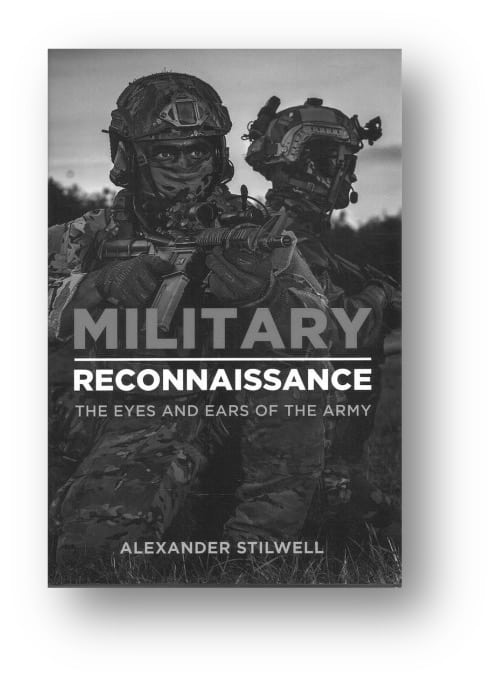

978-1612009506, Casemate, June 2021, 192 pages, $16.00

Reviewed by: Hugh Sutherland, Joint Special Operations University, Tampa, Florida, USA

Military Reconnaissance: The Eyes and Ears of the Army by Alexander Stilwell is an easy-to-read study of scouting and reconnaissance from ancient times through the conflicts of today and predictions for the future of scouting and reconnaissance. In the introduction, the author asserts that reconnaissance has long been a key tool enabling military commanders to visualize the environment in order to make informed decisions. Stilwell explains that reconnaissance throughout history has been made up of scouts, sundry organizations on the field of battle that can gather information, and, in modern times, that tool incorporates technology. He backs up his observations with numerous examples throughout history of how reconnaissance and scouting have led to victory and how the lack of reconnaissance has led to defeat.

In Chapters 1-3, Stilwell examines the role of scouting and reconnaissance in Ancient Warfare, Medieval Warfare, and the Revolutionary Years, respectively. Ancient Warfare is examined in the context of ancient Greece and Rome, while Medieval Warfare is primarily focused on conflicts in Europe with some study of the conflict between the Byzantines and Muslims in the 10th and 11th centuries. Chapter Three looks at the development of scout and reconnaissance organizations in the 18th and 19th centuries and the role of those organizations in the revolutionary wars in Europe, the Americas, and the Napoleonic conflicts.

In Chapter 4, “Beyond the Frontiers,” Stilwell studies the expansion of imperialism in the 19th century and how scouting and reconnaissance were an integral part of what he calls “exploratory reconnaissance,” aiming to give competing nations the advantage in the quest for new lands and the defense of the same. As perhaps the most interesting chapter of the book, this chapter looks closely at the famous scouts of the 19th century with an examination of the requisite skills required for successful reconnaissance. Stilwell then gives numerous examples of both victory and defeat in conflict, largely resulting from either proper or improper application of scouting and reconnaissance.

Chapters 5: “The First World War,” and 6: “The Second World War,” are true contrasts of how different situations led to the development of different tools. In this case, the static nature of trench warfare in World War One is contrasted against the mechanized maneuver warfare of the Second World War. Though World War One started with varying degrees of horse cavalry usage, it soon bogged down to trench warfare and the need for observation of the enemy from static positions. This observation was done by troops patrolling between the lines, snipers, and “Battle Observers” whose function was to track and report developments during the fighting. Working with scouts, the Battle Observers would cue the scouts to areas of interest in preparation for offensive or defensive action. Though Stilwell did not go into great detail, he does briefly cover the development of aerial reconnaissance from the early days of balloons to the use of aircraft for reconnaissance in depth of the enemy forces. Stilwell concludes Chapter 5 with an examination of the interwar period of 1918-1939, in which he explores the shift to aerial, motorized, and then armored reconnaissance by the belligerents of the soon-to-be-fought Second World War. In Chapter 6, Stilwell begins with a brief study of the development of tactics, techniques, and procedures used by the reconnaissance forces of the Germans, French, British, and then later, the American forces. In this chapter, he also goes into a fascinating examination of the role of specific scout and reconnaissance units that were instrumental to success in several key battles in both the European and Pacific theaters.

Chapter 7: “The Cold War Years, 1950-1982,” is a global look at military reconnaissance from the Korean War through the British experience in the Falklands War in 1982. In this global look over time, Stilwell starts with conventional reconnaissance assets like the Marine 1st Reconnaissance Battalion in the Korean War and finishes with Special Operations units like the Special Boat Service in the Falklands. Using multiple vignettes throughout the chapter, Stilwell notes that the different reconnaissance units and personnel manning them have different capabilities and requirements that are based upon their expected employment and areas of operation.

The final chapter, “Military Scouting, the Global War on Terror, and Beyond,” is followed by the author’s conclusions. In the final chapter, Stilwell looks at conflicts from the Gulf War of 1990-1991 to Operation Enduring Freedom (2001-2014) and concludes with Operation Iraqi Freedom (2003-2011). This chapter is mostly a series of vignettes that detail the employment of SOF and conventional forces in several of the battles that were key to the three conflicts, but the chapter concludes with an examination of the units, equipment, and organization of many of the military reconnaissance units.

The author’s conclusions start with an example of the United States Army deactivating most of its long-range surveillance companies and the equipping of a Parachute Infantry Battalion with miniature reconnaissance drones as technology increasingly enables the force to better accomplish its mission. He then gives examples and an explanation of the value of using Special Operations Forces for reconnaissance because of their placement and function on the battlefield. To be clear, Stilwell does not advocate abandoning traditional reconnaissance forces, but he does advocate the use of technology to better perform the mission, whether it is done by conventional or special forces.

While this book is an easy-to-read, interesting exploration of the history and critical role of military reconnaissance, it has a few faults that detract from its credibility. Throughout the book, there are numerous spelling errors, typographical mistakes, and disjointed paragraphs that leave the reader wondering why they were included. These problems should have been addressed with more thorough editing. Despite these flaws, Military Reconnaissance: The Eyes and Ears of the Army provides valuable insights into the evolution of scouting and reconnaissance, making it a worthwhile read for military historians, analysts, and practitioners interested in the subject.

Hugh Sutherland is an instructor at the Joint Special Operations University (JSOU), specializing in combating terrorism.