Robert C. Jones, U.S. Special Operations Command, MacDill AFB, Florida, USA

“Look deep into Nature, and you will understand everything better.” —Albert Einstein

CONTACT Robert C. Jones | robert.jones@socom.mil

The views expressed in this publication are entirely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views, policy, or position of the United States Government, Department of Defense, or United States Special Operations Command. © 2025 Arizona State University

The principal reason the United States struggles with irregular warfare (IW) is its deeply flawed understanding of insurgency. Getting insurgency right is perhaps the most important intellectual challenge facing the Joint Force today. If we find ourselves in a war with a peer competitor, the centrality of insurgency will fade—but in the current era of increasingly contentious competition, effectively relieving or leveraging insurgency is key to nearly everything: from greater stability at home to reducing the threat of violent extremists abroad and more effectively deterring problematic acts of state competition. Getting insurgency right is indeed the proverbial nail, for want of which the kingdom might be lost.

In literature and doctrine, insurgency is a chameleon with a dozen names and infinite manifestations. Whether we call it “insurgency,” “insurrection,” “rebellion,” “revolution,” “resistance,” “instability,” “resilience,” “stability,” “civil resistance,” or even “violent extremist organizations,” we are ultimately describing shades of the same fundamental human dynamic. At its core, insurgency arises when a population, formed around a distinct identity, perceives itself to be in existential conditions of legally irreconcilable political grievance. An active insurgency occurs when that same population then acts illegally—under the laws of the government they are challenging—through violent or nonviolent means to address those conditions. Our world today is rife with both latent and active conditions of insurgency. The nation that best understands and addresses these conditions will hold the advantage in the current competition.

So, why is no one talking about insurgency? Frankly, we have moved on. State challengers like China, Russia, and Iran took full advantage of a United States distracted by the attacks of 9/11 to press their positions “around the edges”[1] of the empire. The Joint Force is now appropriately focused on deterring and, if necessary, confronting these major state actors. Meanwhile, insurgency has been tucked away, bundled into the much larger collective construct of IW.

One of the goals of this article is to clarify the role of IW as an organizing framework and highlight the critical importance of understanding, as clearly as possible, the fundamental nature of insurgency. This article is built around a proposed critical distinction between the nature of a problem and its character. One way to think about this distinction is that the nature of a problem encompasses everything that it must be—and nothing that it need not be. In 1905, Albert Einstein disrupted the world of physical nature by publishing works based on “thought experiments” rather than physical ones.[2] In thought experiments, he used his imagination to visualize how the variables in nature interacted with the constants to devise new theories to explain the challenges of our physical world. Here, we apply the same logic to human nature. If the constants of a problem constitute its nature, then the variables of the same problem provide its character. The doctrine and literature of the challenges associated with IW are heavily premised on the character, as historically, the application of overwhelming state power could typically shape the character of a situation into one deemed acceptable by the state. However, as the modern information age shifts relative power from states to populations, these character-based approaches are proving too difficult, costly, provocative, and fleeting. By first determining the distinct nature of a problem, we can better imagine how the variables of character might interact and then develop more accurate theories for understanding the myriad human dynamics within the family of challenges we call “irregular warfare.”

Let Us Be Clear: “Irregular Warfare” Is Not Something We Do; Irregular Warfare Is Something We Made

We are free to name and define manmade conceptual constructs like IW as we please. However, such is not the case with natural dynamics such as those found within IW. Fundamental human dynamics, such as insurgency, are rooted in the nature of mankind. These must be studied carefully, guarding against the pull of bias, emotion, and popular trends. Ultimately, we must understand our way to greater success, but if we are not mindful, we run the risk of defining our way to failure. The Department of Defense (DoD) has redefined IW yet again, yet efforts to develop a more accurate understanding of the diverse human dynamics within IW remain largely unchallenged and unexplored.

IW is a bureaucratic fiction—but is it a useful one? To know the definitions[3] of IW is a straightforward task. Over the past 20 years, the U.S. has paved a meandering path of definitions and doctrine to support this body of knowledge, and experts on IW abound. Yet, during this same era—guided, advised, and led by these experts—the U.S. has struggled mightily with a wide range of irregular challenges and adversaries. This is as true domestically as it is abroad and applies as much to state actors as to non-state actors. Clearly, a substantial gap remains between our knowledge of IW and our understanding of the diverse human dynamics bundled within. This is the gap between “the right answer” and “the good answer.” And in an era of unprecedented change, that gap between doing things right and doing things well has never loomed larger.

When creating a strategic construct, it should be simple, logical, necessary, and helpful to its intended purpose. It should provide a figurative table where diverse parties with shared problems but divergent missions can gather. It should stimulate new understanding, synergy, and opportunities for greater success. Unfortunately, IW has never quite met that standard. With the non-negotiable requirement that it be a form of warfare, the latest rendition of IW was purposely created by the DoD for the DoD. Rather than creating a table to gather around, it builds a wall that divides. Rather than fostering a greater understanding of the diverse dynamics within, it creates a false sense that IW is somehow a distinct entity unto itself.

The prescient challenge with IW lies in our understanding of the problems it seeks to address. These problems cannot be defined into submission, nor can our struggles in implementing IW solutions be redefined into success. Naturally occurring human dynamics are indifferent to what we wish them to be. Efforts to conform nature to bias are perhaps our greatest folly—and the central problem of conflicts inaccurately described as “endless wars the Generals can’t win.” These were not wars that could not be won; they were policies that could not be enforced. The essential failure occurred at the moments of decision but played out over decades of bloody, expensive, frustrating execution. A better understanding of underlying problems will inform better decisions.

Why? Because IW is not any one thing—it is a collection of things. While many of these share important characteristics, they vary tremendously in their nature. These nuances are becoming increasingly important, yet they are often ignored or misunderstood in doctrine. In a bygone era—prior to electronic communications, when much of our IW knowledge was formed—states could typically ignore and overcome these distinctions through the application of power and a monopoly on legal violence. And yes, through warfare. But that era has long since passed.[4] In truth, this has not been the case for some time. Show me an “endless war the Generals can’t win,” and I will show you a situation where military power was applied in vain attempts to coerce a government or population into accepting policies or laws they deemed illegitimate, inappropriate, unjust, or intolerable. The inertia of outdated doctrine, literature, and experiences is strong, and we have yet to fully grasp this modern reality: where policy is impossible, all approaches are infeasible. Our challenges are as much a matter of obsolete direction as they are outdated definitions. And in the military’s “can do” culture, these two forces feed upon each other.

Evolving Conditions, Shifting Definitions

Rarely has the adage, “where one stands depends upon where one sits,”[5] been more relevant than in the realm of IW definitions. This is reflected in the many redefinitions of IW by the DoD in recent years. For centuries, IW was simply warfare not conducted by regular forces. The DoD resurrected and repurposed the term to address the frustrations of the post-9/11 era.

In the early 2000s, we focused on the character of the contest at that time. In 2007, frustration set in, leading to the admission that “IW is a complex, messy, and ambiguous social phenomenon that does not lend itself to clean, neat, concise, or precise definition.”[6] By 2010, an attempt was made to impose a tighter framework, defining IW[7] as “a violent struggle among state and non-state actors for legitimacy and influence over the relevant population(s).” This definition, like many before it, included embedded explanations: “Irregular warfare favors indirect and asymmetric approaches, though it may employ the full range of military and other capabilities, in order to erode an adversary’s power, influence, and will.” At its core, IW was effectively defined as a violent struggle for legitimacy and influence.

By 2020, however, the emphasis on “violence” became problematic in the context of a new National Defense Strategy[8] that emphasized “competition below armed conflict” and mandated the application of IW[9] across every aspect of that competition. The solution was simple: delete the “violence” requirement. The new definition read, “Irregular warfare is a struggle among state and non-state actors to influence populations and affect legitimacy,” while keeping the second sentence unchanged. At this point, IW was essentially everything—and therefore explained nothing. It was now framed as a struggle to influence populations and affect legitimacy. At this point, IW was beginning to sound more like democracy than warfare, while including both. The growing population within the Department of Defense who see everything as some form of warfare, and warfare as what the Department of Defense does, were unhappy with this definition. With the coming of a new administration, two things were made clear: IW would be redefined yet again, and any Pentagon definition of IW would emphasize the “warfare” aspect of the concept.

The latest effort to redefine IW is now complete. The all is warfare,[10] and warfare is all we do contingent won out. Now, IW is “a form of warfare where state and non-state actors campaign to assure or coerce states or other groups through indirect, non-attributable, or asymmetric activities.”[11] Nearly every aspect of this definition raises cause for concern. It overstates the role of warfare, redundantly highlights the inclusivity of the concept, and artificially categorizes the ways in which IW must be conducted. To be fair, this definition will likely serve its intended administrative purpose. To take definitions like this literally for what they convey, however, is problematic. After 20 years of struggling with mis-framed problems, obsolete doctrine, and overly symptomatic solutions yielding few durable, desired strategic effects, this is probably not the definition the nation needs to effectively address the challenges IW is intended to address.

Crossing the Rubicon: Not So Much Irregular as Illicit

We continue to struggle with the critical first step: identifying the problem. As a legitimate entity confronting illegal and often violent challenges, we carry an inherent bias. Viewing these challenges through a warfare lens naturally leads us to look for threats to defeat as a critical step to solving the problem. Too often, this results in waging warfare against symptoms while leaving underlying issues unaddressed—or worse, exacerbating them. We need to do better in understanding the challenges of IW.

The current landscape of IW challenges can be divided into four distinct categories: (1) transnational crime, (2) gray zone challenges, (3) insurgency-based challenges, (4) and terrorism. Each of these categories is fundamentally different by its nature but often overlaps or appears similar in character. Understanding these distinctions is critical for formulating the right strategic responses.

- Transnational Crime:[12] Illegal for profit. These activities, conducted by state or non-state actors, are illegal under the laws of the systems being challenged. Their primary purpose is for profit. Regardless of how violent or disruptive governance crime may become, it is not warfare or insurgency and cannot be resolved through warfare or counterinsurgency (COIN) approaches.

- Gray Zone Challenges:[13] Illegal to expand one’s sovereignty. These activities, conducted by state actors, are illegal under the laws of the systems being challenged. Their purpose is to advance sovereign privilege. When conducted legally, these challenges constitute competition, regardless of how frustrating they may be.

- Insurgency-based Challenges:[14] Illegal for politics. These are population-based activities leveraged by state or non-state actors. They are illegal under the laws of the system being challenged.[15]

- Terrorism: Illegal to coerce through fear. These activities, carried out by discrete organizations or individuals, are illegal under the laws of the system being challenged. Their purpose is to generate fear to affect changes in law or behavior. Despite expansive lists of terrorist organizations, true terrorist entities are rare.[16] Notably, organizations like al-Qaeda and the Islamic State are accurately classified as insurgency-based challenges rather than terrorism-based, as they wage unconventional warfare (UW) campaigns reliant on preexisting insurgencies.

Most of these challenges do not manifest as warfare, nor are their methods particularly irregular. However, these activities are problematic to U.S. interests and security, and the DoD must remain prepared to counter such activities.

To frame challenges accurately, we need to explore better questions. The nature of a challenge should drive policy and strategy, whereas its character (symptoms) should inform effective tactics. Certain questions are essential for understanding the nature of problems. When faced with a new situation, we should ask ourselves a series of framing questions:

- How much does this issue threaten or advance U.S. interests?

- Is this challenge legal under the laws of the system being challenged?

- Is this conflict within a single system of governance or between two or more?

- What is the primary purpose for the challenger(s)’s actions?

- What are the relationships between the parties?

- Are the laws and norms being violated necessary and just?

- What are the critical identities relevant populations are forming around?

- Have recent events shifted the priority of identities in significant ways?

- Do affected populations recognize both the legitimacy and character of the governance affecting their lives?

- How do populations feel about the governance affecting their lives and whom do they blame and/or credit?

- Do affected parties believe they have trusted, legal, and effective mechanisms to address their grievances or interests?

By asking better questions, we can more accurately classify and understand IW challenges to set the conditions for arriving at better answers.

A Pragmatic Alternative: An Alternative Definition and Recommendations

In pragmatic terms, IW is perhaps best understood as a collection of problematic, illicit challenges deemed important by the Department of Defense and their legitimate solutions. This perspective removes loaded, subjective words like “warfare” or “legitimacy” and instead focuses on the single, common aspect of the four distinct types of challenges bundled under the IW banner: legality—or, more accurately, their illegality under the laws of the system being challenged.

Shifting the focus to illicit activity moves attention away from a particular threat or preferred solution, opening the door to a more holistic and effective analysis of the fundamental problems at hand. The military is no longer a “hammer” that has preidentified “nails” with an implied leadership role. Instead, the military becomes a tremendous source of resources and capabilities, postured to support and advance U.S. national interests in this era of restive peace. Viewed through this lens, the following recommendations emerge:

- Shift the focus from the problematic symptoms labeled as “threats” and work to better understand the fundamental nature of the problems driving the current surge in illicit challenges.

- Clearly communicate that collectively, IW is much more an administrative construct than an operational one. IW ensures that the DoD remains prepared to assist in addressing illicit challenges today while maintaining the readiness to fight and win in potential future conflicts.

- Emphasize that most of these challenges are rarely acts of war and cannot be resolved through the application of warfare. These are not threats to “defeat,” nor are these conflicts to “win.” The primary role of the military is to help create time and space for relevant authorities to make appropriate adjustments, provide additional capacity where requested, and help deter, mitigate, and disrupt high-end illicit violence.

- Clarify that, outside the context of formal war, effective IW solutions are typically led by agencies other than the DoD or by other nations. The U.S. military does not “wage” IW; it conducts IW activities.

To this end, we must, to the best of our abilities, attempt to understand the implications of this rapidly evolving strategic environment—particularly, how these changes are shaping the character of competition and conflict. Most importantly, we must ensure that we understand the nature of the unique challenges we face.

What is nature? The nature of a situation is a capture of everything it must be, and the release of everything it need not be. However, determining the nature of a problem is not a reductionist process, it is a refining one. A refined understanding, free of unnecessary character-based impurities, serves as the foundation for durable, simple, and effective strategic concepts. Ultimately, all these challenges are human dynamics, and as such, like warfare, their strategic nature is rooted in human nature. The best safeguard against institutional, emotional, and situational bias is a clear understanding of the distinct and fundamental nature of various types of challenges. There is no substitute for getting the problem right from the outset. Why? Because standing in the emotional wake of events like 9/11, January 6, or October 7 is not the time to craft unbiased understanding or develop measured, effective responses given the outrageous character of what has occurred.

We stand at a historic inflection point, living in an era of unprecedented change where the advantage currently lies with the revisionists. Unlike the United States, which is wedded to sustaining a waning and increasingly challenged status quo, our revisionist adversaries recognize the opportunities inherent in the emergent strategic environment far better than we do. They intentionally dodge hard “red lines” and seek to provoke predictable responses to validate their narratives and advance their respective causes. When we cling to flawed or obsolete perspectives on the challenges we face, we accelerate our own decline. We must shift our efforts from redefining our solutions to reframing our problems. Once a problem is clear, new solutions will naturally follow.

Legitimate Solutions: Our Current Menu of IW Activities

Once we have identified the problems, we can then turn to the family of solutions. The latest version of IW includes a set of IW activities—each akin to musical notes that must be arranged and orchestrated to fit the nature and character of the problem at hand. Nuance is everything, and it begins with a fundamental understanding of the problem. Only once the problem is understood, and its objectives are clear and feasible, can we begin to design a campaign that purposefully orchestrates these activities. To say one “conducts irregular warfare” is a dangerous oversimplification—but we absolutely conduct IW activities and those must be tailored in ends, ways, and means for modern realities. These activities include:

- Civil Affairs Operations (CA)

- Counter Threat Network

- Security Cooperation

- Counter Threat Finance

- Security Force Assistance (SFA)

- Civil-Military Operations

- Military Information Support Operations (MISO)

- Counterinsurgency (COIN)

- Counterterrorism (CT)

- Foreign Internal Defense (FID)

- Stability Operations

- Unconventional Warfare (UW)

Each of these activities is defined and described in U.S. military doctrine. In this era of tremendous change, doctrine will naturally lag behind reality. Just as governments everywhere struggle with the friction of a governance gap, so too do militaries everywhere suffer from a doctrine gap. If our understanding of insurgency is indeed flawed, then the way we think about nearly all of these activities is flawed as well. Now is the time to ensure we understand the problems we seek to address in the most fundamental terms possible, by their respective natures. This will then allow us to tailor our activities to mitigate the problematic symptoms surrounding these problems while patiently advancing durable, desired solutions.

The Pursuit of Understanding

Figuratively speaking, the old playbook is obsolete. Throughout recorded history, nations have employed their power to exercise some degree of control over the people and places where they perceived their interests to lie. They aligned with, coerced, bought, or created governments willing to prioritize those foreign interests over those of their own people—and then protected those governments against all challengers, foreign or domestic. We think of ourselves as “exceptional,”[17] but this distinction lies more in the character of our actions than in the nature of our approach. The character of one’s actions can soften the sting and mitigate the response, but it is the nature of those actions that shape the nature of the response. For example, until we can appreciate how the failed U.S. involvement in Afghanistan shares fundamental similarities with the failed Soviet involvement in the 1980s, we will learn little from our experience. Some argue that we need to execute the old playbook more vigorously.[18] Certainly, we have the power to force our will upon whomever we please, but is that the nation we imagine ourselves to be? Instead, we need to understand why modern efforts fall short, and adjust our ends, ways, and means accordingly.

The definition of “winning,”[19] for most irregular problems has traditionally been defined as defeating a bad actor while ensuring challenged governments remain in power, unchanged, and uncoerced. This is not solving the problem; this is merely suppressing the symptoms. It is a measure of success drawn from 500 years of Western colonialism. Once success is framed in this context, it is natural to fixate on the problematic symptoms rather than the deeper causes. What was once, literally, “good enough for government work,” is no longer adequate to serve our interests at home or abroad. In fact, the pursuit of some degree of control has become an expensive, provocative, and unnecessary liability. The good news is that we can serve our interests far more effectively through relative positive influence, and the rules-based order advanced by the U.S. is uniquely suited to an influence-based approach. However, the bad news is that our current toolkit of IW activities is built on obsolete understandings of the problems they were designed to address. These tools are overly employed to create degrees of control rather than to foster shades of influence. If we are to remain effective in the modern era, we must update our toolkit, as well as our playbook.

A Hypothesis and Some Insights

A decade ago, when General Joseph Votel was the Commander of the United States Special Operations Command (USSOCOM), he faced a problem. With a growing gray zone challenge facing the nation, he had to find a way to shift Special Operations Forces (SOF) engagement to be less reactive. The challenge, however, was how to validate shifting efforts to the “left of bang” when the Special Operations Forces were already operating at full capacity—100 percent committed right of bang while meeting 50 percent of operational requirements. It was in this environment that Doctor Tom Nagle and I prepared the Strategic Appreciation[20] signed by General Votel in 2015. To achieve better answers, we needed to ask better questions. We needed a new theory of the case.

Our hypothesis was simple: we were living in an era of rapidly shifting power while wrestling with the friction caused by slowly adjusting policies, governance, and redistribution of sovereign privilege. In simple terms, we were in a governance gap. The resultant grievances from these perceived imbalances were creating a growing energy for conflict both within and between states. These challenges were as old as humankind, but in the modern information age, the speed, scope, and scale were unprecedented. Traditional approaches were proving too controlling, more provocative, and less effective. Governments everywhere were struggling to adapt, and revisionist actors saw opportunities where status quo actors saw threats. To get in front of these problems we had to think like a revisionist.

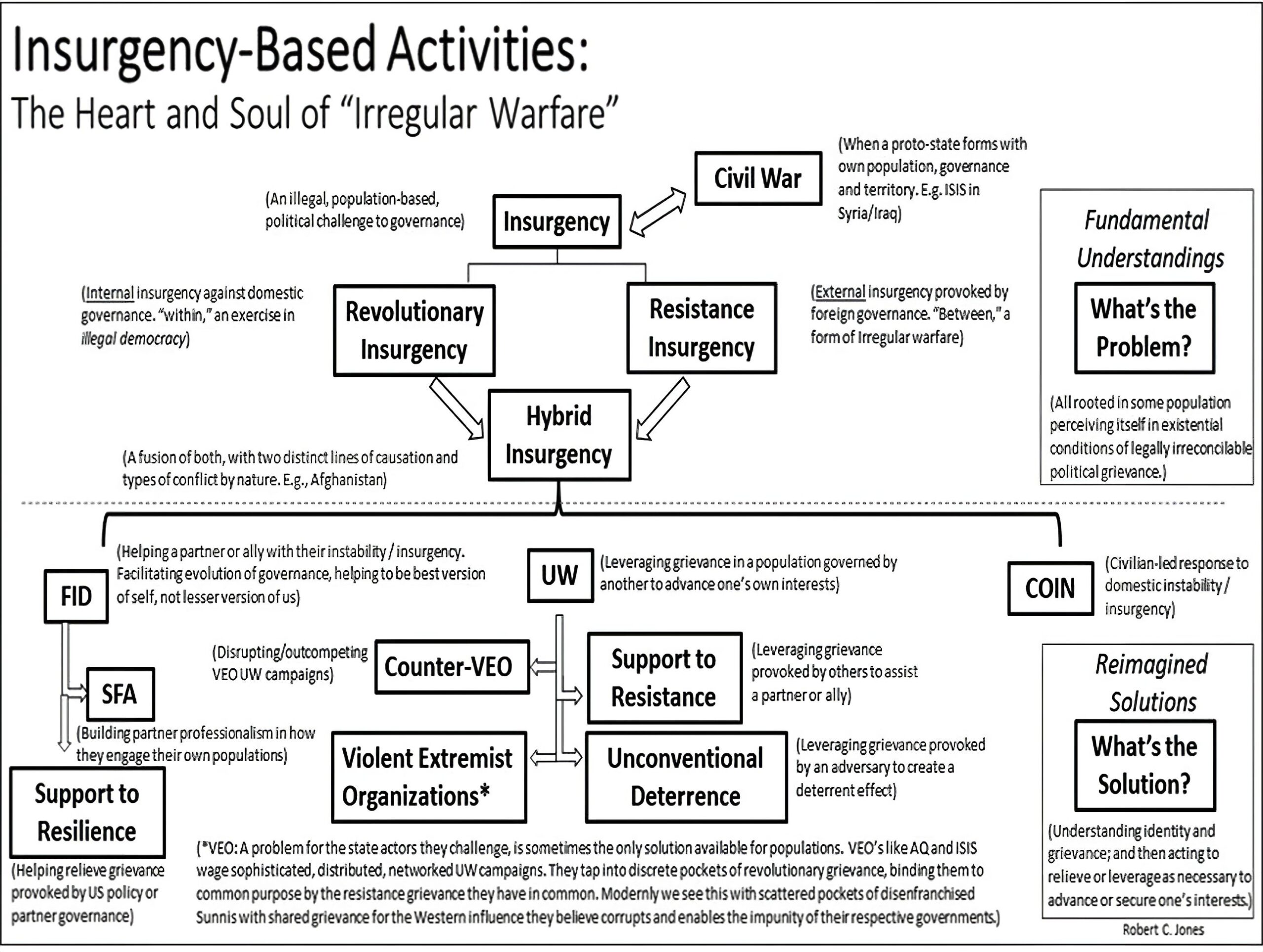

Thinking like a revisionist and conducting “thought experiments,” I have come to the following insights on population-based conflicts. Many of these perspectives challenge long-held positions and are difficult to prove correct—but they could easily be proven wrong if flawed. They are presented here for consideration, discussion, and challenge. These insights also inform the attached chart (see Figure 1) and are shaped, but not constrained, by U.S. military doctrine, professional literature on insurgency, and my experience as a Special Operator.

- Conflict within a single system is fundamentally different from conflict between two or more systems. This distinction is a function of the relationships between the parties. War theory is rooted in conflicts between two or more systems and is largely sound. Where we run into trouble is applying war theory to non-war problems, particularly those occurring within a single system of governance, where relationships endure. Revolutionary insurgency, for example, may look like warfare by its character, but by its nature, internal revolution is more akin to democracy, albeit illegal democracy. While perhaps violent, it is an expression of democracy all the same. Revolutionary symptoms can be suppressed through warfare, but the drivers of revolutionary problems are invariably made worse by such efforts. Fully appreciating this single point of understanding is arguably the keystone to resolving most of our IW challenges.

- Population-based challenges are like water. The character of water can be gas, liquid, or solid within a very narrow range of conditions. The same is true of challenges rooted in a population perceiving itself to be in legally irreconcilable political grievance. These conditions can shift rapidly in character—ranging from artificially stable to active illicit challenges to full-scale civil war. It is far easier to change the character of the conflict than it is to resolve the nature of the problem—particularly when solutions are designed to treat the population’s symptoms rather than addressing governance as the primary cause.

- The vast majority of IW is a derivative of insurgency. Our doctrine and literature on insurgency are a collage of loose terms and overly descriptive definitions, replete with gaps and overlaps. We describe how things look, rather than seeking to understand what they are and why they occur. The heavy bias of colonialism and the outrage of governments and populations facing illegal, often violent challenges have historically cast the state as the victim, rather than the provocateur.[21] Getting to a better understanding of the nature of insurgency is the most vital task for improving our ability to resolve irregular problems or implement irregular campaigns of our own.

Figure 1: Insurgency-Based Activities

Some Insights on Insurgency

If one looks at insurgency in the way framed above, certain things become clear. First, all insurgencies must possess the following three characteristics: illegal under the laws of the system being challenged; primarily political in purpose; and population-based in nature. Though the character of insurgency takes on myriad forms, they fundamentally fall into two distinct types (along with a hybrid form):

- Revolutionary insurgency: Internal to a single system of governance and therefore best understood and addressed as an act of illegal democracy. If war is the final argument of kings, then revolution is the final vote of the people. Revolution is within. Perhaps the most critical insight for IW may be this: the only fundamental difference between revolutionary insurgency and democracy is legality!

- Resistance insurgency: Insurgency provoked by external sources of governance, and therefore a form of irregular war. Resistance is between.

- Hybrid insurgency: A fusion of revolutionary and resistance causation and reaction among the same populations. This demands recognizing both distinct problems in forming policy and solving for each in strategy. Tactically, it all looks the same on the ground. To solve for only one is folly (e.g., Afghanistan, 2001-2021).

- Center of Gravity: The driving energy behind insurgency is a population perceiving itself in existential conditions of legally irreconcilable political grievance. Understanding causation allows for early assessment of a population’s relative resilience or exploitability long before conflict exists. A greater appreciation of political grievance allows governments to proactively reduce unnecessary provocations and foster natural stability.[22]

- Ideology: A critical requirement to enhance, direct, or accelerate grievances, but is rarely causal in and of itself. An effective ideology speaks to the culture and grievances of the target population(s) and takes positions the challenged government(s) are unable or unwilling to adopt. (Therefore, the most effective way to disempower an insurgent narrative is not to “counter” it, but rather to agree with the rational aspects, incorporating them into one’s own narratives and actions.)

- Character: Variable factors, such as geography, history, culture, the use of violence, the type of ideology employed, and the stated goals of the insurgent group all appear to be merely aspects of the character of an insurgency. These factors are important for refining tactics but are largely irrelevant in determining the nature of the problem at hand, or in shaping feasible policies or effective strategies.

- Civil War: Too often linked to the scale of a conflict or the degree of violence, civil war begins when a proto-state emerges from insurgency with its own territory, population, governance, and security. This is the “ice” (solid) form of insurgency. To defeat the character of a civil war by deconstructing the proto-state, simply convert the conflict back to “liquid” (active insurgency) or “gaseous” (latent insurgency) forms—e.g., The Islamic State in Syria/Iraq.

- Winning: For a challenged government to truly win, it must address the governance factors driving the insurgency. Historically, focusing on defeating the insurgents while preserving an unchanged status quo has merely suppressed the symptoms of insurgency rather than resolving its root causes, an approach rarely viable in the modern information age. This is a lesson the U.S. should have learned from its post-9/11 misadventures, and one that Israel needs to strongly consider today as they respond to the attacks of October 7, 2023. While insurgents can win at any point in the contest if they can coerce the challenged government to change, a government can only win once it evolves sufficiently to bring grievance and trust within manageable norms.

- Popular Legitimacy: This is the recognition of a governing authority’s right to affect people’s lives. This is perhaps the most significant factor in the cure/cause of insurgency. U.S. doctrine overly fixates on legal legitimacy, which is the recognition of a government by external institutions and actors. This has been a particularly problematic issue for the U.S. in recent conflicts. Believing the foreign governments, we attempt to create and protect are legitimate, rather than appreciating them as collaborative, has blinded us to the infeasibility of policy decisions for regime change or nation-building. The reality is that any government born of a foreign power is de facto illegitimate—making it a natural target for revolutionary insurgency. Likewise, our own efforts as foreign actors are equally de facto provocative of resistance insurgency towards ourselves. While our valid motivations for engaging in such behavior, our good intentions, and efforts to avoid excessive violence and collateral damage are noble – it is the nature of our actions that drove the nature of the affected population’s response.

On the bottom half of Figure 1, proposed reimagined solutions are presented. Here, I apply the fundamental understanding of insurgency, as captured in the upper half of the figure, to the goals and guidance of our most recent strategic documents—all within the context of the modern information age. Viewed in this manner, IW—particularly the insurgency-based aspects of irregular warfare—becomes a powerful array of activities for advancing and securing interests in competition, as well as deterring gray zone challenges and major conflicts. These break out under three major headings: Foreign Internal Defense (FID), Unconventional Warfare (UW), and Counterinsurgency (COIN).

Historically, FID has been focused on preserving a partner government or keeping an ally in power, typically over the objections of a significant segment of its own population. This approach, straight out of the old colonial playbook, is premised on maintaining control to preserve foreign governments in power we see as favorable to our interests. However, in today’s modern world, this has been an increasingly expensive, confrontational, and unnecessary provocation. FID to control foreign political outcomes is nearly fully obsolete in the post-Cold War era. Moving forward, FID must be more about fostering positive influence, respecting sovereignty, and promoting self-determination. It should be focused on empowering partners to become better, more inclusive versions of themselves—not lesser versions of us.

Additionally, SFA has historically sought to foster durable relationships through training, equipping, and advising foreign military. Yet, when conducted in developing countries, this approach too often resulted in creating smaller, lesser versions of U.S. forces that tended to be culturally unsuitable and fiscally unsustainable. When these forces were crafted for governments lacking a broad writ of popular legitimacy, they rarely possessed the fighting spirit of the insurgent forces they were meant to counter. One observation from Operation Enduring Freedom–Philippines was the power of respecting host nation sovereignty and focusing on improving the relationship between security forces and the populations they encounter. Our SFA efforts, severely constrained by narrow authorities, permissions, and funding, forced us to be more strategic than we otherwise wanted to be.[23] It turns out that showing a greater respect for the sovereignty of the host nation forced us to empower, rather than transform, thereby reducing the resistance-producing provocations of our efforts. Simply improving the professionalism and character of the interactions between Philippine security forces and the populations in remote areas soon resulted in dramatic improvements in the stability of the region.

There is also support to resilience. Historically, resilience efforts have tended to focus on basic human needs, and while this remains a vital area of assistance, moving forward, we must be far more attuned to political resilience. The former relates more to the lower half of Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, while the latter aligns with the upper half. Improving our understanding of the fundamental nature of insurgency allows us to more accurately assess whether a population is resilient or exploitable and adjust our efforts accordingly. Invariably, the political resilience of a society is far less about the conditions in which a population lives and far more about how they feel about living in those conditions—and whom they blame for their situation.

Next up is COIN. Our COIN successes are typically fleeting at best, and our COIN failures are humiliating disasters of epic proportions. Why? Because we relied on flawed and obsolete perspectives and applied the same term—“COIN”—to the activities of both the host nation and the external nations or forces involved. This may seem like a minor point, but the negative consequences of this conflation of roles cannot be overstated. When the roles are conflated, it is far too easy for a more capable external power to take an inappropriate leading role. This subjugation of the host nation invariably serves to validate the grievances of the relevant populations, amplify the narratives of the insurgent or UW organizations supporting those populations, and foster resistance energy towards the external power.

This is precisely why COIN is best thought of as a civilian-led, domestic operation, in which the role of the military is the same as in any civil emergency: to be last in and first out; to provide the necessary extra capacity; to never supplant civil authorities; and to always remember there is no military victory to be had. The military serves primarily to mitigate and disrupt the high end of violence and to help create the time and space civil authorities need to adjust their governance, as necessary, to reduce provocations and restore order. Foreign powers do not conduct COIN, they conduct FID and must do so in a manner designed to foster positive influence, always careful not to provoke resistance or inadvertently enhance revolutionary grievances against the host nation.

UW – Leveraging Insurgency for Purpose

Perhaps the most misunderstood activity of all is UW. The reasons for this misunderstanding fall primarily on the special operations community. We have become so enamored with and trapped by our historical applications of UW that we struggle to free our understanding from the artificial constraints imposed by that bold history. While there are a handful of variations of the UW definition, they typically involve several artificial constraints drawn from historical examples, such as those in occupied Europe during WWII or the bold “horse soldiers” who leveraged the Northern Alliance to topple the Taliban government in Afghanistan. The standard components of these definitions focus on activities occurring in a denied space, working with some blend of local underground, auxiliary, or guerrilla organizations, and efforts to coerce or overthrow adversary regimes. But UW is far more than just supporting a resistance or revolutionary insurgency.

To fully appreciate both the challenges and opportunities of UW, we must first free this concept from unnecessary factors of its historic character and come instead to understand it in terms of its fundamental nature. We must capture everything it must be and release everything it need not be. UW is perhaps the most powerful tool in our IW activities tool kit and is simply, fundamentally, naturally, just this: UW is any activity designed to leverage the legally irreconcilable political grievance in a population governed by someone else, to advance one’s own interests.

There is no adversary approach more frustrating to the U.S. in the post-Cold War era than the modern application of UW. The Russians employed UW when they seized Crimea without a fight and again through its use of social media to inflame political grievances, shape elections, or foster instability in the United States. Both al-Qaeda and the Islamic State have waged UW since their respective inceptions. Iran conducts UW in their support of Hamas in Gaza or the Houthis in Yemen. Yet, none of these adversaries care a whit what our special operations doctrine writers or senior leaders wish our nostalgic vision of UW to be. Our definitions and doctrine have become a trap we have built for ourselves and willingly climbed inside. The certainty of our knowledge blinds us to the unconstrained approaches applied with tremendous success by our adversaries. We are trapped by the “right answer,” while alternative approaches are in practice all around us.

One such alternative approach is unconventional deterrence.[24] In simple terms, this is posturing to create a credible threat of UW in the mind of an adversary. Traditional approaches to deterrence are of little use in deterring the illicit “gray zone” acts of competition that erode the sovereignty of important partners and allies and undermine the credibility of the rules-based international order. However, illicit competition and the corruption it fosters are also powerful sources of legally irreconcilable political grievances that SOF is uniquely trained to identify and leverage. This capability can be used to help an at-risk partner foster greater resilience or to create uncertainty in adversaries about SOF’s abilities to destabilize dozens of global efforts they see as essential to their ambitions. By freeing UW from its artificial constraints, we empower SOF to create new lines of deterrence. These new forms of irregular deterrence help shrink the gray zone and integrate into broader deterrence strategies designed to reduce the risk of war.

Labeling organizations like al-Qaeda or the Islamic State as “terrorist” groups is perhaps our greatest modern example of framing a problem for how it looks, rather than for what it is. By recognizing that these Violent Extremist Organizations (VEOs) are most accurately illegal, non-state political action groups, waging sophisticated, distributed, and networked approaches to UW (and yes, employing terrorist tactics), we free our minds to craft new and more promising solutions.

VEO campaigns are wholly reliant upon hybrid insurgency. This involves a combination of populations desperate for help in addressing their revolutionary grievances with domestic governance, then uniting around common resistance grievances against foreign governance. Recognizing the nature of this problem empowers us to shift our focus from the problematic symptoms associated with these campaigns, focusing instead on solving the actual problems of obsolete and inappropriate policies and governance. We must disrupt these campaigns and mitigate their violence—but do so in ways that create time and space for civil authorities to address the policy and governance failures that resistance and revolutionary insurgency-based VEO UW campaigns exploit. We must create better narratives, rather than simply countering theirs. A key approach is to co-opt effective elements of the VEO narrative while presenting a superior alternative. Lastly, we must outcompete these organizations as the partner of choice for advancing the evolution of better and more inclusive governance for disenfranchised populations around the planet. We must counter their UW campaigns, not just their terrorist tactics.

One powerful way to improve IW, therefore, is to reframe and expand UW. Ultimately, whether one is conducting UW to coerce or overthrow some adversary; create new lines of deterrence; become more strategically effective in dealing with VEOs; or foster resilient populations at home and abroad, these actions are all rooted in insurgency and variations on a fundamental perspective of UW.

Special Warfare – That Distinct Subset of Irregular Warfare Unique to SOF

Competition is the framework for a whole-of-society effort to advance and secure our national interests. Irregular warfare nests within this framework as a responsibility of the entire Joint Force. One way to appreciate the role of SOF is to view special warfare as a distinct subset of IW. To be clear, special warfare is not a form of warfare, per se, but rather a mechanism for clarifying roles, missions, and activities appropriately tasked to our Special Operations Forces from those better executed by conventional forces or other entities.

From inception, USSOCOM was directed by law to focus only on certain activities “in so far as it relates to special operations.”[25] Joint Doctrine clarifies this mandate by explaining how “special” is situational and rooted in a unique set of conditions that must combine to make any activity a “special operation.”[26] This is enlightening on several levels. First, no operation is inherently “special” simply because of the character of the unit performing the task or the type of task being performed. Secondly, this perspective challenges the idea that the conventional force somehow became “more SOF-like” during the post-9/11 era. As missions traditionally assigned to SOF units expanded to the rest of the Joint Force, it was SOF that inadvertently became more conventional, rather than the other way around.

By the time the U.S. left Afghanistan, SOF had evolved, taking on a hyper-conventional focus. We were far more focused on threats than problems, and our population-based roots had atrophied. USSOCOM was giving the nation the SOF it wanted, but were we giving the nation the SOF it needed? Even today the demand signal from our nation’s capital remains weighed toward the hyper-conventional. The challenges in breaking this inertia of expectations are significant. Yet, the question facing USSOCOM today is: What modern roles, missions, and activities are not only “special” but also relevant to addressing emerging challenges and serving current strategic guidance? Reshaping and refocusing our SOF presents challenges wholly distinct from the one of reimagining irregular warfare, but ones also demanding a firm grasp of the fundamental nature of the problems facing our nation and the world.

Conclusion

To be clear, man-made, administrative constructs like “integrated deterrence” or “irregular warfare” are all vitally important to the defense community. They help highlight challenges and organize our thinking. But when we create these constructs, they must be accurate, simple, and helpful for their intended purposes. We must also remain humble in our thinking and pragmatic in our actions. Too often we lose sight of this—particularly when the challenges before us appear overwhelming and unresponsive to our efforts. This is why we must strive to see through complexity and understand the fundamental aspects of these challenges. These are challenges that cannot be defined into submission, nor do they care a whit about our biases, fears, or preferences. They simply are, and we have a duty to understand them for what they are and address them accordingly. In the current environment—in the current era of competition—the most important human dynamic to understand accurately is that of “insurgency.” This is truly that proverbial nail, for want of which the kingdom might be lost.

Insurgency is a dynamic with many closely related cousins. Here, I write for the defense community in the context of irregular warfare, so I focus on the insurgency variant. If writing for other audiences, I could just as easily focus on resilience or political stability. Ultimately, we look at similar problems, describing them in differing terms, but we must understand them for what they truly are. When people perceive themselves to be in existential conditions of legally irreconcilable political grievances, a force for instability grows within them. These conditions cannot be wished or defined away, or solely attributed to our adversaries—but they are conditions we can understand, resolve, or leverage for purpose.

Governments around the world are struggling with the growing challenge of populations, formed around discrete identities, perceiving themselves as trapped in conditions of legally irreconcilable political grievance. When these conditions exist, the exploiters of grievance will emerge. Armed with clever narratives designed to raise those perceptions to existential levels, these exploiters seek to mobilize at-risk populations for malign purposes. It is natural to cast blame, perpetuate victimhood, and seek to punish, suppress, or defeat the actors, rather than to defuse the conditions. After all, the state will always be the legal actor and has the right and duty to enforce the rule of law. However, shifting blame and attacking only the symptoms primarily serves to validate exploiters’ narratives and deepen the population’s grievances. In the past, suppression of symptoms was often good enough. Increasingly, it is not.

Perhaps the greatest obstacle in getting good answers to modern challenges is the guardians of the right answers derived from pre-information age experiences. Recently, when General Fenton suggested that USSOCOM’s contribution to a comprehensive scheme of integrated deterrence included fostering new lines of irregular deterrence,[27] it sent Pentagon staff officers scrambling for their military dictionaries. Because it was not in “the book,” the concept was dismissed and left to whither. It is time to challenge “the book.” It is time to re-examine long-standing assumptions –ideas believed to be facts—and question whether they are merely calcified assumptions colored by the biases of a bygone era. As the modern information age shifts the balance of power, new truths are being revealed, and many old practices are rendered obsolete.

At no time in history has there been a larger gap between the “right answers” of the past and the “good answers” needed for the future. This is particularly true in the inherently human dynamics of governance, competition, and conflict. Now is not the time to draw false comfort from doctrine and definitions. Now is the time to understand how the current information age is affecting the character of these dynamics and to craft new approaches that foster stability, which increasingly eludes our efforts. Ultimately, human dynamics are shaped by human nature and played out across countless scenarios—indifferent to what we wish them to be or what side we are on. Make no mistake: the challenges and solutions bundled within IW are incredibly important. We have a new definition but let us be clear-eyed about the work that remains. Now is the time to shift our focus to understanding problems for what they are—and to designing and applying solutions that will produce the results our security and interests demand.

Robert C. Jones is a retired U.S. Army Special Forces Colonel and currently serves as a U.S. Special Operations Expert with the Ministry of Defense, Tunisia. Previously, he spent over a decade as a senior strategist for U.S. Special Operations Command. He holds a Juris Doctorate from Willamette University College of Law and a Master’s in Strategic Studies from the U.S. Army War College. Additionally, he is a non-resident fellow at the Center for Advanced Defense Studies (C4ADS).

[1] Admiral Eric T. Olson and Michele Flournoy, “Back to the Future: Resetting Special Operations Forces for Great Power Competition,” Podcast, Irregular Warfare Initiative, 2020.

[2] Norton, John (1991), “Thought Experiments in Einstein’s Work,” in Horowitz, Tamara; Massey, Gerald J. (eds.), Thought Experiments in Science and Philosophy (Maryland; Rowman & Littlefield; November 1991), 129–148. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 June 2012.

[3] Jared M. Tracy, “From “irregular warfare” to Irregular Warfare – History of a Term,” Veritas, Vol. 19, no. 1, (2023), https://arsof-history.org/articles/v19n1_history_of_irregular_warfare_page_1.html.

[4] Lawrence Korb, “The Real Reason We Can’t Win Wars Anymore,” National Review, 21 March 2021, https://news.yahoo.com/real-reasons-u-t-win-103057654.html?guccounter=2.

[5] Rufus Miles, “The Origin and Meaning of Miles’ Law,” Public Administration Review. 38 (5): 399–403, September 1978.

[6] IW Joint Operating Concept (JOC) 1.0, 2007.

[7] “Irregular Warfare: Countering Irregular Threats,” Joint Operating Concept, Version 2.0, 17 May 2010, /https:/www.jcs.mil/portals/36/documents/doctrine/concepts/joc_iw_v2.pdf?ver=2017-12-28-162021-510.

[8] “Summary of the 2018 National Defense Strategy of the United States of America – Sharpening the American Military’s Competitive Edge.”

https:/dod.defense.gov/Portals/1/Documents/pubs/2018-National-Defense-Strategy-Summary.pdf

[9] “Summary of the Irregular Warfare Annex to the National Defense Strategy,” 2020. https:/media.defense.gov/2020/Oct/02/2002510472/-1/-1/0/Irregular-Warfare-Annex-to-the-National-Defense-Strategy-Summary.PDF

[10] Micah Zenko, “How Everything Became War: A Conversation With Rosa Brooks,” Council on Foreign Relations, 7 November 2016, https://www.cfr.org/blog/how-everything-became-war-conversation-rosa-brooks.

[11] Joint Publication 1, Vol 1: Joint Warfighting (CJCS, August 2023).

[12] U.S. Department of Defense, DoD Counter-Drug and Counter-Transnational Organized Crime Policy, DoD Instruction 3000.14, (Washington, D.C.: Department of Defense, 2020) https://www.esd.whs.mil/Portals/54/Documents/DD/issuances/dodi/

300014p.pdf?ver=2020-08-28-112340-617.

[13] Summer Myatt, “2022 National Defense Strategy to Prioritize Gray Zone and Hybrid Warfare Plan, Optimized Data Sharing,” GovConWire, 25 January 2022, https://www.govconwire.com/2022/01/

2022-national-defense-strategy-to-prioritize-gray-zone-hybrid-warfare-and-data/.

[14] Joint Chiefs of Staff, Counterinsurgency, JP 3-24 (Washington, D.C.: Joint Chiefs of Staff, April 2008), https://www.jcs.milPortals/36/Documents/Doctrine/pubs/jp3_24.pdf?ver=

giaAj5fgP4SGt_BdkOrkNA%3d%3d.

[15] Robert C. Jones, “Deterring ‘Competition Short Of War’: Are Gray Zones The Ardennes of Our Modern Maginot Line of Traditional Deterrence?” Small Wars Journal, 14 May 2019. https://smallwarsjournal.com/index.php/jrnl/art/deterring-competition-short-war-are-gray-zones-ardennes-our-modern-maginot-line

[16] Terrorist Designations and State Sponsors of Terrorism – United States Department of State https://www.state.gov/terrorist-designations-and-state-sponsors-of-terrorism/

[17] Mary McMahon, “What is American Exceptionalism”? United States Now, 6 November 2023, https://www.unitedstatesnow.org/what-is-american-exceptionalism.htm.

[18] Jacqueline L. Hazelton, “Book Excerpt, ‘Bullets Not Ballots, Success in Counterinsurgency Warfare,’” Military Times, 17 May 2021, https://www.militarytimes.com/opinion/commentary/

2021/05/17/book-excerpt-bullets-not-ballots-success-in-counterinsurgency-warfare/.

[19] Christopher Paul, Colin P. Clarke, and Beth Grill, “Victory has a Thousand Fathers: Success in Counterinsurgency,” Rand Corporation, https://www.rand.org/pubs/monographs/MG964.html.

[20] United States Special Operations Command, “Strategic Appreciation,” 2015,

[21] Joint Publication 3-24, “Counterinsurgency,” 25 April 2018.

[22] Robert C. Jones, “Lies, Damn Lies and Assessments,” pp. 9-17, Strategic Multilayer Assessment White Paper “What Do Others Think and How Do We Know What They Are Thinking?”, Joint Staff J39, March 2018.

[23] David P. Fridovich and Fred T. Krawchuk, “Special Operations Forces: Indirect Approach,” Joint Forces Quarterly, 2007.

[24] Robert C. Jones, “Strategic Influence: Applying the Principles of Unconventional Warfare in Peace,” Strategic Multilayer Assessment, Joint Staff J39, June 2021.

[25] U.S. Code Title 10, Section 167: “special operations activities include each of the following insofar as it relates to special operations.”

[26] Joint Chiefs of Staff, Special Operations, JP 3-05 (Washington, D.C.: Joint Chiefs of Staff, July 2014), GL-11, https://irp.fas.org/doddir/dod/jp3_05.pdf. Special Operations is defined as “Operations requiring unique modes of employment, tactical techniques, equipment and training, often conducted in hostile, denied, or politically sensitive environments and characterized by one or more of the following: time sensitive, clandestine, low visibility, conducted with and/or through indigenous forces, requiring regional expertise, and/or a high degree of risk.”

[27] Katie Crombe, Steve Ferenzi and Robert Jones, “Integrating Deterrence Across the Gray – Making it More Than Words,” Military Times, 8 December 2021, https://www.militarytimes.com/opinion/

commentary/2021/12/08/integrating-deterrence-across-the-gray-making-it-more-than-words/.