Cody Chick, Naval Postgraduate School, Monterey, California, USA

What began as a plan to establish weather stations in mainland China to support the U.S. Pacific Fleet quickly evolved into a vast resistance network aligned with Chinese guerrillas, disrupting Japanese forces across the country. The Sino-American Cooperative Organization (SACO, pronounced “Sock-O”) was a bilateral partnership between Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalist government and the U.S. Navy. It merged Chinese intelligence networks with American resources to create a combined-joint command capable of executing the full cycle of find, fix, and finish against Japanese targets. SACO initially focused on weather reporting but gained momentum after integrating with the Nationalists’ intelligence apparatus. The result was a coordinated effort that forced Japan into a strategic dilemma: confront the U.S. naval fleet in the East or face Allied armies advancing from the West.

CONTACT Cody Chick | kod91@aol.com

The views expressed in this publication are entirely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views, policy, or position of the Naval Postgraduate School, Department of the Navy, or Department of Defense. © 2025 Arizona Board of Regents / Arizona State University

Despite significant challenges within the China-Burma-India (CBI) Theater, by the end of World War II, SACO’s efforts culminated in measurable success and demonstrated the potential of future U.S.-backed guerrilla warfare campaigns. With only 2,500 U.S personnel, SACO managed to train nearly 100,000 guerrillas by mid-1945.[1] The development of necessary infrastructure, training camps, and theater-wide permissions took several years, but paid off once SACO was fully operational by 1944.[2] Although SACO was originally focused on meteorology and intelligence, its leadership ultimately exceeded expectations and fulfilled a broader strategic directive. SACO’s integration with China’s intelligence network and shifting U.S. strategic priorities allowed it to become a key actor in guerrilla warfare operations. As guerrilla columns were trained, they gained notoriety for sabotage, target acquisition, and their ability to disrupt large conventional forces on land and at sea.

SACO is a remarkable, yet often forgotten, piece of history that serves as a case study for the use of U.S.-supported guerrilla warfare with the Republic of China (ROC) against an overpowering aggressor—characterized by Japan yesterday, and potentially the People’s Republic of China (PRC) tomorrow. Like most crisis-generated WWII special operations, SACO was dissolved after the war ended. Still, SACO presents a unique case study to examine the challenges of bureaucratic infighting, coalition-building with national parties in political turmoil, and the factors that made the organization effective. This article uses qualitative research with select primary sources in a historical narrative to demonstrate how SACO’s mission, organizational model, challenges, and overall results provide an example of the advantages and risks relevant to unconventional warfare today. SACO’s unique U.S.-ROC partnership against an occupying power highlights enduring challenges—particularly relevant amid growing tensions between the People’s Republic of China, Taiwan, and the United States: contested logistics, command and control, population control, and cost imposition.

From Weather Stations to Guerrilla Armies: SACO’s Mission

In 1939, Commander Milton “Mary” Miles had returned from the Asiatic Fleet and was serving on the Navy’s Interior Control Board (ICB) in Washington, D.C. He had previously served in China on the Yangtze River Patrols, beginning in 1922 and again in 1934.[3] His experience fostered a deep fascination with Chinese culture, and he became fluent in Mandarin during his deployments. In 1941, Chief of Naval Operations Admiral Ernest King directed Commander Miles to “go to China and set up some bases as soon as you can for the U.S. Navy landings in three or four years. In the meantime, do whatever you can to help the Navy and to heckle the Japs.”[4] Acting on broad marching orders, Miles began by meeting his intelligence counterpart.

Upon arriving in China, Miles met with the U.S. Naval Attaché, Colonel James McHugh, and then went to meet Dai Li, the head of the Military Bureau of Investigation and Statistics (MBIS). Dai Li was Chiang Kai-shek’s chief of intelligence, known for his vast network across China and his fervent loyalty to Chiang—particularly in tracking Chinese communist activity and defending against Japanese forces. Prior to 1941, Dai Li had worked closely with Britain to train a guerrilla force tasked with conducting sabotage operations against Japan. However, the scheme ultimately failed, as Dai Li was deeply suspicious of outside organizations with colonialist pasts and was determined to maintain operational control over all actions taken within China.

Milton’s success depended heavily on his ability to gain Dai Li’s trust. Upon their first meeting, Miles understood the importance of rapport and gift-giving within Chinese culture, presenting Dai Li with a camera and a snub-nose revolver similar to his own. This simple act conveyed the message that he saw Dai Li as an equal he respected, not a subject to exploit for his own purposes. Following that meeting, James McHugh, the Naval Attaché, wrote to the Secretary of the Navy, “[Miles] has seen and done things I never thought any foreigner would be able to do.”[5] Miles’ cultural fluency, language skills, and ability to build rapport were critical to securing a foothold in China’s intelligence network.

Within weeks, Miles set off on an expedition to survey the Chinese coast. The expedition aimed to provide Admiral King with an initial report on Japanese control and the potential for establishing weather stations throughout southern China. During those weeks, Miles came to grasp the scale of Dai Li’s intelligence network—and with it, an opportunity to rapidly expand U.S. influence in China’s guerrilla campaign. On June 9, 1942, after arriving in Pucheng to meet with members of the Military Bureau of Investigation and Statistics (MBIS), their presence in the city was compromised, and Japanese aircraft continued bombing runs through the area.

It was at this moment that Dai Li offered Milton Miles the key to what would become a combined-joint U.S.-Sino irregular warfare campaign. Dai Li proposed that Miles help train 50,000 guerrillas to fight the Japanese. In return, Dai Li would help establish weather stations, provide intelligence, and appoint Miles a general in the Chinese Army to assist in commanding irregular forces.[6] Understanding Admiral King’s intent—and recognizing the rare opportunity offered by Dai Li—Miles agreed. He saw his initial objectives evolve from weather reporting into the creation of a combined-joint organization with tangible operational impact. Together, they saw real potential to coordinate resistance against Japan’s occupation and to attrit Japanese forces through sustained guerrilla pressure.

China was well-positioned for guerrilla warfare. Since the fall of the Chinese empire in 1911, the country had endured feuding warlords, economic hardship, and an internal civil war between the Chinese Nationalists and Communists. While China had a large population willing to fight, it lacked institutional training and resources. In 1937, following near-extinction at the hands of the Nationalists and occupation by the Japanese, Mao Zedong wrote On Guerrilla Warfare. In his essay, he astutely notes:

Guerrilla warfare has qualities and objectives peculiar to itself. It is a weapon that a nation inferior in arms and military equipment may employ against a more powerful aggressor nation. When the invader pierces deep into the heart of the weaker country and occupies her territory in a cruel and oppressive manner, there is no doubt that conditions of terrain, climate, and society in general offer obstacles to his progress and may be used to advantage by those who oppose him. In guerrilla warfare, we turn these advantages to the purpose of resisting and defeating the enemy.[7]

While China did not have the materiel or training necessary, it could leverage its advantages in manpower and territorial size to hamper Japanese military objectives. When paired with U.S. training and coordinated with “the operations of… regular armies,” China would be positioned to resist—and eventually overcome—Japanese occupation.[8] In light of the advantages of a U.S.-Sino partnership, Milton Miles and Dai Li shaped a mission for their organization. The two men began formalizing the partnership, drafting a bilingual document that combined Chinese military and U.S. naval interests: establishing an organization to train, equip, and conduct guerrilla warfare, in addition to intelligence collection and weather forecasting. On April 1, 1943, the agreement for the Sino-American Special Technical Cooperative Organization (later shortened to SACO) was signed and approved by U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt and Chinese Nationalist President Chiang Kai-shek.[9]

Organizing a Combined-Joint Agency

Dai Li was designated as the director of SACO, and Captain Miles was appointed as the deputy director, but both had veto power for major decisions.[10] Appointing a Chinese director was essential to maintaining the partnership, given China’s historic distrust of foreign motives rooted in past alliances. Given the divergent goals that often accompany irregular warfare, carefully structured frameworks are essential for building mutually beneficial partnerships. This structure dignified the Chinese position and ensured they were fully invested, while incorporating checks and balances to align each nation’s goals. For Dai Li and Miles, their roles were distinct, but they shared operational decisions. Both leaders maintained administrative control of their respective countries’ soldiers, but operational decisions were first mutually agreed upon by both leaders and approved by Chiang Kai-Shek himself, with oversight from the U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff.[11] SACO’s chain of command shifted after General Stilwell was replaced by General Wedemeyer, who amended the agreement to place SACO under U.S. theater control rather than under Chiang Kai-shek.[12]

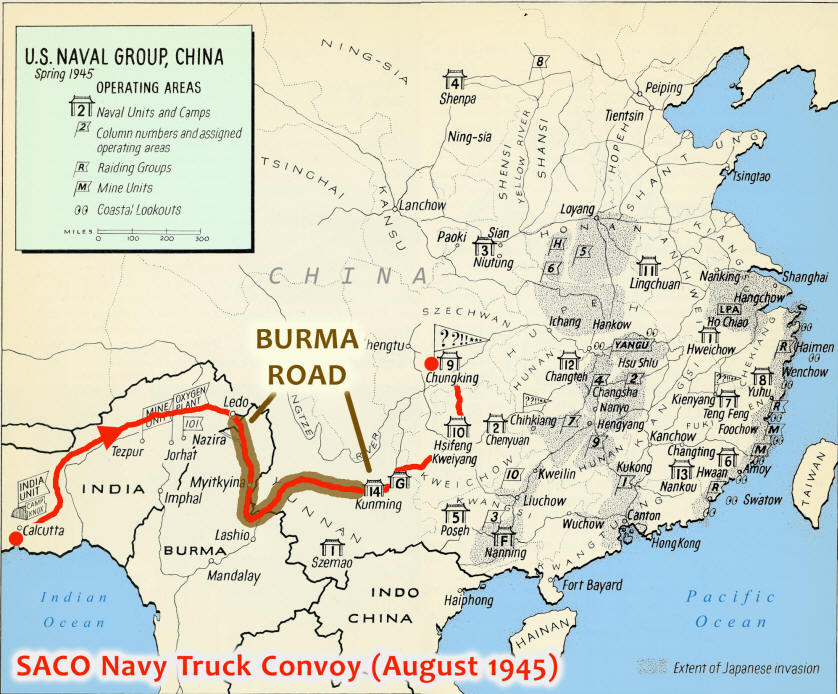

SACO slowly expanded from its headquarters in Happy Valley near Chungking, ultimately stretching from the edge of Indochina to Mongolia by the end of 1945. What began as a small schoolhouse to train guerrillas and intercept radio messages grew into a broader network, with the establishment of thirteen training camps, as shown in Figure 1. According to author Linda Kush in The Rice Paddy Navy:

While the curriculum varied by location, all camps taught small arms, grenades, demolition, scouting and patrol, ambush, close-range fighting, and teamwork in the field. Camps close to water included instruction in coast watching, ship identification, mining, and underwater demolition, while those near air routes added aircraft identification. Soldiers likely to work in urban areas got special training in street fighting.[13]

Within Happy Valley, SACO mirrored traditional staff structures, appointing Chinese and American directors and deputies based on expertise, and eventually establishing a combined-joint headquarters to streamline communication.[14] As SACO established training camps, each one was placed near Japanese lines of control. Each camp partnered with guerrilla columns, allowing trainees to plan operations during instruction and join combat missions immediately after graduation.[15]

Figure 1: SACO Operations and Logistics Route by Spring 1945[16]

Although China offered vast terrain for operations, Captain Miles had to import nearly all equipment due to the country’s limited internal resources. Japan controlled and closed the Sea Lines of Communication along the Chinese coast, making maritime supply routes inaccessible. As a workaround, U.S. forces shipped equipment to Calcutta, India, then airlifted it “over the Hump” of the Himalayas. Describing this route, the National Museum of the United States Air Force noted, “despite being the closest point for supply distribution, the Assam Valley in India was still 550 miles from China. To fly the ‘Hump,’ transport aircraft would take off from just 100 feet above sea level in India and climb at a drastic rate of 300 feet per minute until they reached 18,000 feet to navigate the Himalayan Mountains.”[17]

Barbara Tuchman, in her biography of General Stilwell, Stilwell and the American Experience in China, 1911–1945, emphasized that for every ton of munitions dropped by General Chennault’s Air Force, 18 tons of supplies were required to support it. The Hump alone caused approximately 13 plane wrecks per month, meaning that by the time materiel completed the journey—via ocean shipping, railroads, flights, and final transport by rivers and roads—much of it never reached the resistance forces at the end of the 13,500-mile trip.[18] Additionally, SACO had to compete for materiel with General Stilwell’s forces, who were charged with outfitting 30 Chinese divisions.

From 1941 to 1945, there was no direct way to ship materiel to China. With no direct maritime option, SACO and the Navy relied entirely on the Army to transport personnel and supplies from India. SACO even contributed to the effort by supplying additional oxygen, which increased the Army’s monthly tonnage capacity from 3,500 to 22,000 tons. [19] Unfortunately, SACO remained a low priority and received far less tonnage than General Stilwell had originally allocated.

This scarcity severely hindered U.S. efforts to support Chinese resistance forces and contributed to General Stilwell’s relentless push to reopen the Ledo Road from India to China through Burma. The Allies lost control of the Ledo Road in the spring of 1942—the only land line of communication into China—and did not regain it until 1945.[20]

Despite its modest size, SACO required extensive logistical infrastructure to sustain operations across a wide geographic footprint. In response to transport delays, SACO established facilities in Calcutta, India, to hold personnel and equipment until they could be flown over the Hump. In India, SACO built housing for incoming personnel, a radio relay station, an oxygen plant to support air transport, and a printing facility for maps, training materiels, and operational forms.[21] With the flow of personnel bottlenecked in India, these facilities enabled SACO to put idle staff to work until they could fly onward to headquarters.

Challenges for an Emerging Organization

SACO faced considerable challenges: it was a Navy unit operating in an Army-controlled theater, partnered with Chinese forces, and constrained by limited space and resources. Though united in their goal of defeating Japan, each party had different ideas about how to achieve it—and competed for influence wherever possible. In this environment, SACO struggled to execute its mission amid bureaucratic infighting, constrained logistics, and battlefield limitations. These challenges consumed valuable time and energy, ultimately reducing SACO’s overall impact. By the time SACO was fully operational and capable of conducting large-scale guerrilla warfare, the Axis had fallen in Europe, and the Pacific war was winding down.

SACO’s most significant obstacle was inter-service rivalry over who controlled the unit and its capabilities. Initially, Miles served as head of Naval Group China, operating under the U.S. Navy with oversight from the China-Burma-India (CBI) Theater Commander, General Stilwell. General Claire Chennault, in a letter to Miles, captured the frustrations many leaders faced in the CBI Theater:

I always found the Chinese friendly and cooperative. The Japanese gave me a little trouble at times, but not very much. The British in Burma were quite difficult sometimes. But Washington gave me trouble night and day throughout the whole war![22]

Under the SACO agreement, Miles reported directly to Chiang Kai-shek and the Joint Chiefs of Staff—not to the theater commander. This frustrated both General Stilwell, who eventually accepted it, and General George Marshall, who favored a consolidated command structure for land forces.[23] Miles also held the title of Chief Naval Observer at the American Embassy—a position the embassy interpreted as placing him under its authority. These overlapping chains of command—each with competing objectives—were further complicated by the arrival of the Office of Strategic Services (OSS).

Following Japan’s strike on Pearl Harbor, “Wild” Bill Donovan, head of the OSS, moved quickly to establish an intelligence network in East Asia. Recognizing a gap in U.S. intelligence efforts in China, he sought to develop clandestine operations and intelligence collection directly under his command. Frustrated by the Navy’s reliance on Chinese intelligence, Donovan envisioned a single, globally integrated network under U.S. control. Under his agent, Esson, he launched the “Dragon Plan,” which aimed to build a network in China and along Japan’s borders, ultimately using Korean partisans to operate against the Japanese mainland and occupied territories.[24]

However, with SACO already operating in China, Miles was designated the OSS coordinator for activities within the country. Like Donovan, Dai Li sought total control over intelligence and aimed to eliminate all foreign organizations outside his jurisdiction. By 1942, Dai Li succeeded in folding U.S. intelligence activities into the SACO agreement with the Nationalist government. At first, Donovan accepted this arrangement. The OSS even supported SACO by providing equipment and training, including 100,000 single-shot pistols known as Woolworths—a contribution the Navy would have struggled to procure independently.

Although initially cooperative with SACO to avoid Army interference, Donovan quickly resumed efforts to establish OSS autonomy. He resisted having OSS operations subject to Miles and Dai Li, particularly as he sought cooperation with the Chinese Communists—a prospect both SACO leaders rejected outright. On October 27, 1943, the Joint Chiefs of Staff issued directive JCS 11/11/D, placing all OSS activities under the control of the relevant theater commander.[25] At this point, Donovan had alienated Miles but still needed a way to conduct independent operations in China—something neither Miles nor the Nationalists would permit. In a final effort to remove Miles, Donovan attempted to have him relieved from both SACO and the OSS. To protect Miles and preserve SACO’s autonomy, Admiral King convinced President Roosevelt to promote him to Commodore—equal in rank to Donovan—and to remove him from embassy oversight. This move prevented the embassy from claiming him and ensured Donovan could not usurp his authority in SACO.[26]

One of SACO’s greatest challenges involved defining the U.S. advisor role within the Chinese partner force. Dai Li initially insisted that American personnel train guerrillas but refrain from accompanying them into combat. He justified this as politically necessary and a matter of honor—arguing that Chinese forces would not tolerate U.S. trainers being killed under their watch. Critics of Dai Li, however, claimed this restriction allowed him to divert resources toward anti-Communist efforts instead of fighting the Japanese.[27] In the case of one instructor, he “led his guerrillas up to the moment of attack, at which point they shunted him to the rear for fear that he would be wounded or worse.”[28] Under these conditions, SACO’s American personnel could only provide equipment and instruction. After repeated mission vetoes and growing frustration, Dai Li eventually allowed U.S. servicemembers to accompany guerrilla forces in the field. This marked a major turning point, transitioning SACO from an “advise-only” model to an “advise-and-assist” role—though the greatest resistance had come from the partner force itself.

The challenges SACO faced—interservice rivalry, logistical constraints, conflicting authorities, and friction with partner forces—remain highly relevant today. SACO’s experience underscores both the enduring value and persistent challenges of irregular warfare in combined-joint, multi-domain environments.

The Effects From SACO

Within a few years, SACO’s efforts bore fruit, emerging as the primary force harassing Japanese occupation forces in China. The organization grew to encompass thousands of guerrillas operating behind Japanese lines, supported by a vast intelligence network that extended as far as Tokyo. SACO’s effectiveness expanded through its partnership with the 14th Army Air Force and by integrating U.S. advisors into combat missions with Chinese guerrilla units.

Shortly after Miles met General Claire Chennault, who led offensive air operations across China, it became clear their organizations would benefit from close coordination. Chennault’s 14th Army Air Force, working with SACO photographers, captured aerial intelligence on enemy force dispositions.[29] When pilots were shot down—a common occurrence—SACO’s network enabled rapid personnel recovery. Even OSS agents captured in Japanese-occupied Shanghai were sometimes recovered within ten hours. As Milligan recounts in By Water Beneath the Walls, “the bicycle couriers would deliver the [counterfeit] cash in exchange for the prisoner, unfold [a] second bicycle for the prisoner to ride, and lead him to a waiting agent outside the city.”[30] Aerial intelligence and personnel recovery helped the conventional forces better understand their enemy and stay in the fight.

SACO’s partnership with the 14th Army Air Force enabled effective ground-to-air communications and precision targeting. SACO advisors grew adept at coordinating with pilots, relaying intelligence, and guiding airstrikes via radio. At times, they used ground signals to identify specific strike points. With small teams of Chinese and American outposts known as coast watchers, the Army Air Force and Navy destroyed up to 141 Japanese ships.[31] In Xiamen (formerly Amoy), a major port in southern China, coast watchers directed bombers to strike an airfield, a fuel depot, and a Japanese destroyer. These naval targeting efforts—alongside harbor and riverine mine emplacements—forced the Japanese to reroute shipping to areas more vulnerable to submarine attack.[32] SACO’s integrated intelligence and reporting were critical to naval and air operations in identifying and targeting enemy assets.

SACO’s works of sabotage and guerrilla warfare successfully disrupted and fixed numerically superior Japanese forces, preventing their redeployment elsewhere in the Pacific. One summary, compiled by SACO veteran Roy Stratton from alumni records, reported that: “From June 1, 1944 to July 1, 1945, SACO guerrillas, at times led by Navy and Marine Corps personnel, killed 23,540 Japanese, wounded 9,166, captured 291… Destroyed 209 bridges, 84 locomotives…141 ships and rivercraft…Aided in the rescue of 30 Allied pilots and 46 air crewmen.[33] Accounts vary, but some estimates suggest up to 97,000 Chinese were trained and 71,000 Japanese killed.[34] The majority of these actions took place only in the last fourteen months of the Pacific Campaign.

In 1944, Column Four demonstrated SACO’s operational impact. Over three months, the column ambushed a 10,000-man Japanese force, killing 967 with only 14 guerrilla casualties.[35] In one combined-joint operation, a SACO column utilized guerrillas as informants within the city to identify patterns of life and used sabotage to destroy Japanese stockpiles with the perception that the Japanese were surrounded. A force of 6,000 Japanese soldiers ultimately surrendered to a column of just 300 guerrillas.[36] At the end of the war, over 4,000 Chinese puppet troops (working for the Japanese) surrendered to SACO’s First Guerrilla Field Unit in the span of a month. The guerrilla columns were conducting sabotage and ambushes in full force by the beginning of 1945.

SACO’s operations demonstrated the asymmetric advantage of guerrilla warfare in secondary theaters. At the height of their operations, SACO saw a significant return on its investment, disrupting supply lines and the movement of Japanese units. Under darkness, Ensign John Mattmiller pushed off from shore on a “junk” boat with his four guerrillas in “Operation Swordfish” to sabotage a Japanese freighter in Amoy harbor.[37] From their boat, the guerrillas slipped into the water, quietly swimming to the freighter, attaching two magnetic limpet mines. Minutes after their return, the ship erupted in flames. Lieutenant Joe Meyertholen, a coast watcher in Amoy, coordinated airstrikes and ambushes that harassed 4,000 Japanese troops, reportedly reducing the force by 1,018.[38] Lieutenant Phil Bucklew, an experienced diver who had conducted coastal reconnaissance at Normandy and Salerno, planned an ambitious amphibious raid on Amoy Island.[39] His experience would prepare him for additional amphibious missions in the future, eventually establishing the Navy SEALs and becoming known as the father of Naval Special Warfare.[40]

From 1941–1945, U.S. and British conventional forces focused their efforts on the Ledo Road to secure a logistical land bridge that could supply China. During this period, Chiang Kai-Shek largely relied on Chennault’s 14th Army Air Force to strike Japanese positions across China. With very little defense, intelligence, or ground support from conventional forces, SACO and the Chinese guerrillas filled a role that was crucial for disrupting Japanese forces. As historian Andrew Hargreaves of King’s College London writes in Special Operations in World War II, the purpose of irregular warfare is “to compel the enemy to alter their force dispositions unfavorably and expend resources unnecessarily, tying up men and materiel in wasteful tasks.”[41] Within this realm, SACO did an extraordinary job in their last year to attrit Japanese forces and keep them in China instead of reallocating them across the Pacific islands.

Contemporary Applications

SACO’s experience during World War II offers a valuable case study for addressing the challenges of irregular warfare today. Its relevance spans enduring geographic challenges in East Asia, persistent inter-service friction over operational control, and the strategic utility of guerrilla warfare in both peripheral and primary theaters. For the ROC, the asymmetric characteristics of guerrilla warfare present a unique deterrence to the PRC.

As tensions rise in the Taiwan Strait, Taiwan continues to seek ways to deter aggression and defend the island. In January 2022, the ROC established the All-Out Defense Mobilization Agency (ADMA), envisioning a whole-of-society approach to supporting its national defense. Since the onset of the war in Ukraine, Taiwan has reinforced the population with the tools and mindset for defending its country and resisting any occupiers. Just as Ukrainian civilians have sabotaged and impeded Russian advances, Taiwan aims to prepare its population for similar resistance in the event of a PRC invasion. In its 2023 National Defense Report, the ROC outlined a layered “all-out” defense strategy that integrates main forces, garrison units, reserves, and civil defense.[42] The ROC has shifted its defense strategy from primarily investing in high-tech defensive capabilities to include Integrated Air Defense System (IADS), ships, and airpower, to a comprehensive approach that uses the support of its public. SACO’s intelligence network, which grew from Dai Li’s FBI-like Military Bureau of Investigation and Statistics, provides a historical parallel. Similarly, the ROC is now identifying how to incorporate its population into a layered defense framework by building mobilization structures before conflict begins.

Logistics in a Denied Environment

Fundamental to guerrilla warfare is the necessity for a stable logistical backbone. Admiral King is famously credited with saying, “I don’t know what the hell this ‘logistics’ is that Marshall is always talking about, but I want some of it.”[43] For SACO, logistical challenges began with the complex task of shipping personnel and supplies across the Pacific Ocean, through India, and then flying materiel “over the hump” of the Himalayan Mountains. Hindered by mountains in the west and a Japanese-controlled coast on the east, all materiel and supplies were bottlenecked, limiting SACO’s growth.

Today’s contested regions present similarly difficult conditions. The ROC is confined to an island just over 100 miles from the PRC’s coastline—approximately the same distance undertaken on D-Day for the Normandy invasion.[44] Since 2024, the PRC has significantly strengthened its IADS, extending coverage up to 300 nautical miles from its coast, severely limiting the ability to provide conventional support to the ROC if the PRC decides to blockade or isolate the island.[45]

Like SACO’s experience of sustaining operations in a denied environment, modern guerrilla warfare requires a multi-faceted logistics strategy. Pre-conflict preparation is essential to any large conflict; guerrilla warfare depends on outlasting the enemy’s will, which can only be done if they have the supplies to last.[46] During competition, to deter and prepare for potential conflict, the government must prepare secure stockpiles for food, ammunition, and equipment.[47] While much of this can be stored in centralized warehouses, it requires distribution across Taiwan to support local communities and potential guerrilla forces.[48] This can be supplemented with external support through pre-positioned stock. During wartime, guerrilla forces may find most of their auxiliary networks and materiel resupplied through battlefield recovery or acquisition, conducting raids and ambushes on supply lines to support their own unit.

Isolated regions like Taiwan also need to identify unconventional approaches to resupply and sustainable practices in agriculture and food production.[49] While traditional air resupply might not be feasible in the face of PRC IADS, materiel could be delivered in small quantities by unmanned, potentially autonomous vehicles with reduced signatures compared to larger ships or planes.[50] Likewise, building strong auxiliary and underground networks to sustain guerrilla forces will be essential. Learned by necessity, SACO understood the importance of developing its own infrastructure in the region to reduce dependence on external support and to build a close relationship with the native population.[51] Supporting networks can also enable sustainable agricultural practices in remote areas and leverage additive manufacturing to produce drones, replace parts, and support continued combat operations.

The greatest sources of friction for SACO occurred at the strategic-to-operational levels, where political interest and service rivalry threatened SACO’s capabilities.[52] SACO had to navigate competing demands from multiple entities—including each military service and the American embassy—all of which sought some degree of control, oversight, or influence over its activities. These competing interests significantly hindered operational efficiency. Much of the time spent by Miles and his staff was spent working on additional requirements and meetings to clarify the organization’s command and control.

While there is a greater appreciation for combined-joint operations today, future crises will produce new organizations with novel command and control structures. Operational control of units needs to be clearly delineated and supported with the necessary resources to fulfill their mission. Although Operational Plans (OPLANs) often outline command structures in advance, they do not account for organizations established in response to changing conditions. For units to focus on combat operations, it is essential for higher elements to clearly define and set subordinate missions and subsequent requirements.

Training exercises and wargames tailored to contingencies in the South China Sea can help alleviate some of the issues experienced in Stilwell’s theater of operations. Multinational Joint Chiefs of Staff exercises and strategic-to-operational level wargaming exercises both play a key role in identifying organizational tensions and defining clear delineations of command and control. In China during WWII, SACO took advantage of the shift in resources initially, while General Stilwell and later General Wedemeyer sought to keep control of both unit missions and resources. SACO’s mission was effectively hindered because the bulk of its resources went to Army units, and Miles had to spend most of his time fighting for SACO autonomy and navigating the changes from theater commanders and the OSS. Bureaucratic infighting remains a risk today—particularly during conflict in a denied maritime environment, where operational resources may be diverted away from land-based or irregular forces.

Population Displacement in Relation to Guerrilla Warfare

It is important not only to study the role that SACO took in guerrilla warfare, but also Japan’s response and subsequent counterinsurgency methods. Within China, Communist and other rebel forces switched from conventional-style attacks to guerrilla warfare. One Japanese soldier recalled, “wherever we went, we won. The difficulty was that although you beat the Chinese in one place, they were still everywhere else. Every night, we were liable to be harassed by guerrillas.”[53] In 1940, the Communist forces organized a conventional assault known as the “Hundred Regiments” battle, taking the Japanese by surprise. While initially impactful, Japanese forces eventually repelled and broke down the Communists’ conventional military, forcing them to return to guerrilla warfare. In turn, Japanese forces adopted a new counterinsurgency policy known as the “Three All”—kill all, burn all, loot all—which indiscriminately sought to destroy guerrilla safe havens and their civilian support networks.[54]

Beyond physical destruction, the policy emphasized the strategic use of population control and guerrilla warfare. Japan used a stronghold strategy, securing key lines of communication and urban centers to preserve resources and control the Chinese coast.[55] To break down areas of resistance, Japanese forces implemented population control measures to undermine the will to resist. While the utter destruction of towns was part of the counterinsurgency policy, it also involved massive relocations of people to other areas, including detainment and labor camps in China, Manchukuo, and Japan.[56] In the case of one border region, over 17,000 people were deported to Manchuria.[57] In total, 41,862 Chinese were “sent to become slave labourers in Japan.”[58] Historian Mark Selden notes that by 1942, “in North China, Japanese intelligence sources estimated that the population of the base areas had shrunk by almost half from 44,000,000 to 25,000,000.”[59] In addition to the physical removal of potential support for guerrillas, Japan also imported Japanese civilian workers to dilute the population and reduce potential areas of resistance.[60] Within population centers where the Japanese implemented such control measures, both SACO and the Chinese Communists had little leverage outside of intelligence collection. By the end of the war, there were one million Chinese and Koreans relocated to Japan, with 1.5 million Japanese (including soldiers) living within China.[61] The importation of Japanese workers and the relocation of Chinese civilians are often seen as practices of Japanese imperialism and colonization, but they also played a key role in their counterinsurgency campaign to reduce public support for guerrilla fighters.

Population displacement and control measures, historically used to deny support for guerrillas, continue to be effective tactics used today. Population control can significantly intimidate areas to limit interactions with guerrillas based on the opposing actor’s control. Japan’s tight control through the “Three All” policy in large urban areas significantly reduced the population’s interactions with guerrilla forces. On the other hand, increased violence against the public can have the opposite of the desired effect, inciting more people to fight against the occupier. Russia has used population displacement and relocation heavily since 2022, removing Ukrainian civilians from the contested border regions. According to U.S. officials, in 2022, Russia had moved “tens of thousands,” with local reports stating over 402,000 people had been removed from the conflict areas and placed in different camps within Russia.[62] Russian news reported that over 1.9 million people were deported from Ukraine into Russia, which could have a significant effect in undercutting public support against the Russian offensive.[63] Similarly, in the PRC’s anti-extremism campaign in Xinjiang province, over 1.1 million Han government officials were imported to integrate with the local populace in 2017, while over 600,000 Uyghurs were relocated across China to work in government factories.[64] This population displacement is supplemental to the 10% of the Uyghur minority, approximately 1.8 million, that have been settled in “vocational and training centers.”[65]

If Taiwan became forcefully occupied by the People’s Liberation Army (PLA), it would be highly likely the PRC would establish similar population displacement procedures during stability operations in a counterinsurgency campaign. Forces like the People’s Armed Police, which operates heavily in Xinjiang to enforce population control measures, would detain and relocate Taiwanese within areas conducive to guerrilla safe havens, also importing PRC civilian workers and officials into the large population centers to reduce the likelihood of coordinated resistance. For SACO, the guerrillas had the advantage of China’s massive land size to avoid total Japanese control. For Taiwan, the island’s separation by the strait poses an advantage for now, but could quickly become a weakness if the PRC vied for total control.

The Cost Imposition of Guerrilla Warfare

The CBI Theater was not the primary, nor secondary, focus for Allied operations. As a coalition, the Allied forces balanced the Atlantic (European, North African, Mediterranean, Soviet fronts) and Pacific (CBI, Southeast Asia, Pacific Rim Islands) Theaters precariously. Prime Minister Churchill had adopted a peripheral strategy that directed the first half of WWII: to “weaken Germany by attacking its more vulnerable periphery, opening up new fronts in distant theaters… bringing new support for the British-French-Russian Triple Entente, while [forcing] Germany and the other Central Powers to rearrange their military and economic resources to the detriment of their western defenses.”[66] Peripheral campaigns focused on airpower, guerrilla warfare, and attrition—militarily and economically—of the Axis’ strength.[67]

The United States established a “Germany first” policy with England, looking to the war against Japan as secondary. As such, “The U.S. Army’s main role in China was to keep the Chinese in the war through the provision of advising and materiel assistance. As long as China stayed in the war, hundreds of thousands of Imperial Japanese Army soldiers could be tied down on the Asian mainland.”[68] In fact, it is recorded that at the height of occupation, over one million Japanese soldiers were in China, alleviating other fronts of the Pacific.[69] According to historian Max Hastings, the amount was estimated to be 45% of Japanese forces in China.[70] Engaged in a global war against the Axis, guerrilla warfare was instrumental in U.S. strategy through organizations like SACO to attrit and delay Japanese forces and eventually build momentum to provide additional options to take the offensive against the mainland of Japan. If war were to break out across the Taiwan Strait, units trained in unconventional and guerrilla warfare would provide both military options and an indigenous avenue for the people to defend themselves while sabotaging an occupying power.

Guerrilla warfare remains a relevant method that provides options to state and non-state actors seeking to avoid or amplify direct military confrontation. Prior to World War II and after, guerrilla warfare has been a major part of combat operations. During the Cold War, proxy warfare became the main instrument between the nuclear powers of the United States and the Soviet Union, as they supported nearby allies to shape the strategic environment. In the Korean War, guerrilla warfare was prominently used by the Chinese People’s Volunteer Army, as well as the North Korean partisans that the United States supported in 1950 with the 8240th Army Unit under Eighth U.S. Army.[71] Similar guerrilla units were raised with the Mujahideen in Afghanistan and the Montagnards in Vietnam. In the 21st century, non-state and paramilitary forces are similarly used as a method to claim non-attribution and reduce direct military conflict. These smaller, asymmetrical units continue in organizations like the Chinese Maritime Militia, Yemen Houthis, or Hamas in the Gaza Strip.

Conclusion

SACO represents a unique case study of U.S. guerrilla warfare during WWII within a periphery campaign, with a Chinese Nationalist leader as its director. From its inception, SACO was the Navy’s reach into mainland China to provide intelligence, eventually trying to capitalize on Dai Li’s vast network to conduct guerrilla warfare.[72] SACO was plagued with logistical issues and competing interests from the U.S. military services and the OSS. Examining the Japanese occupation highlights the use of population control to reduce the viability of guerrilla warfare—while possibly having the unintended effect of encouraging local resistance. Ultimately, SACO reveals the potential that guerrilla warfare can provide in a secondary theater, utilizing the latent power of the indigenous population to harass the enemy, forcing them to dilute resources from other campaigns.

[1] Benjamin H. Milligan, By Water Beneath the Walls: The Rise of the Navy SEALs (New York: Bantam Books, 2021), 228.

[2] U.S. Department of the Navy, “SACO.”

[3] Linda Kush, The Rice Paddy Navy: U.S. Sailors Undercover in China: Espionage and Sabotage behind Japanese Lines during World War II (Oxford, UK: Osprey Publishing, 2012), 4.

[4] Milton Miles, A Different Kind of War: The Little-Known Story of the Combined Guerrilla Forces Created in China by the U.S. Navy and the Chinese during World War II (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1967), 18.

[5] Benjamin H. Milligan, By Water beneath the Walls: The Rise of the Navy SEALs (New York: Bantam Books, 2021), 192.

[6] Miles, A Different Kind of War, 51.

[7] Mao Zedong, On Guerrilla Warfare (Baltimore, MD: Nautical & Aviation Pub. Co. of America, 1992), 70.

[8] Mao, 69.

[9] U.S. Department of the Navy, “SACO [Sino-American Cooperative Association] in China during World War II,” Naval History and Heritage Command, September 13, 1945, https://www.history.navy.mil/research/library/online-reading-room/title-list-alphabetically/s/saco.html.

[10] Miles, A Different Kind of War, 111.

[11] Kush, The Rice Paddy Navy, 28, 109; T.V. Soong, “Message to Generalissimo Chiang Kai-Shek from the President,” July 14, 1942, Map Room File, Box 10, Folder 1, FDR Library, http://www.fdrlibrary.marist.edu/_resources/images/mr/mr0059.pdf.

[12] Kush, The Rice Paddy Navy, 118–19.

[13] Kush, 129.

[14] Kush, 81-83.

[15] Kush, 67-68.

[16] Source: Del Leu, “SACO: The Sino-American Cooperative Organization,” Dels Journey (blog), accessed October 20, 2024, https://delsjourney.com/saco/saco_home.htm.

[17] “Flying the ‘Hump’ Lifeline to China,” National Museum of the United States Air Force, accessed May 10, 2024, https://www.nationalmuseum.af.mil/Visit/Museum-Exhibits/Fact-Sheets/Display/Article/3627010/flying-the-hump-lifeline-to-china/.

[18] Barbara W. Tuchman, Stilwell and the American Experience in China, 1911-1945 (New York: Random House, 2017), 308–9.

[19] Kush, The Rice Paddy Navy, 87.

[20] Troy J. Sacquety, “Over the Hills and Far Away: The MARS Task Force, the Ultimate Model for Long Range Penetration Warfare,” Veritas 5, no. 4 (2009): 2–18.

[21] Kush, The Rice Paddy Navy, 85-86.

[22] Miles, A Different Kind of War, 259.

[23] Kush, The Rice Paddy Navy, 109.

[24] William Donovan, “Memorandum for the President,” January 24, 1942, PSF, Box 147, #186, FDR Library, http://www.fdrlibrary.marist.edu/_resources/images/psf/psf000768.pdf.

[25] Maochun Yu, OSS in China: Prelude to Cold War (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute, 2011), 121.

[26] Yu, 143.

[27] Yu Shen, “SACO Re-Examined: Sino-American Intelligence Cooperation during World War II,” Intelligence and National Security 16, no. 4 (2001): 159, https://doi.org/10.1080/02684520412331306320.

[28] Milligan, By Water beneath the Walls, 207.

[29] U.S. Department of the Navy.

[30] Milligan, By Water beneath the Walls, 239.

[31] Milligan, By Water beneath the Walls, Note 228.

[32] Kush, The Rice Paddy Navy, 153, 226.

[33] Roy Olin Stratton, Saco-The Rice Paddy Navy (Pleasantville, NY: C.S. Palmer Publishing, 1950), vii.

[34] John Whiteclay Chambers II, OSS Training in the National Parks and Service Abroad in World War II (Washington, DC: U.S. National Park Service, 2018), 416, https://www.ossreborn.com/files/OSS%20Training%20Areas%20in%20the%20National%20Parks%20Chambers.pdf.

[35] Kush, The Rice Paddy Navy, 135.

[36] Kush, 185–86.

[37] Stratton, Saco- The Rice Paddy Navy, 230.

[38] Miles, 502–3.

[39] Stratton, Saco- The Rice Paddy Navy, 239.

[40] Kush, The Rice Paddy Navy, 275.

[41] Andrew L. Hargreaves, Special Operations in World War II: British and American Irregular Warfare (Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 2013), 227.

[42] Editorial Committee, Republic of China, ROC National Defense Report 2023 (Taipei City, Taiwan: Ministry of National Defense, 2023), 94–96, https://s3.documentcloud.org/documents/23973306/taiwan-national.pdf.

[43] John E. Wissler, “Logistics: The Lifeblood of Military Power,” Heritage Foundation, October 4, 2018, https://www.heritage.org/military-strength-topical-essays/2019-essays/logistics-the-lifeblood-military-power.

[44] Jim Thomas, John Stillion, and Iskander Rehman, Hard ROC 2.0: Taiwan and Deterrence through Protraction (Washington, DC: Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments, 2014), 6, https://csbaonline.org/uploads/documents/2014-10-01_CSBA-TaiwanReport-1.pdf.

[45] U.S. Department of Defense, Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China (Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Defense, 2023), 89, https://media.defense.gov/2023/Oct/19/2003323409/-1/-1/1/2023-MILITARY-AND-SECURITY-DEVELOPMENTS-INVOLVING-THE-PEOPLES-REPUBLIC-OF-CHINA.PDF.

[46] Gabriel W. Pryor, “Logistics in the Indo-Pacific: Setting the Theater for a Conflict Over Taiwan,” Army Sustainment 56, no. 1 (Winter 2024): 20.

[47] Alex Wang Ting-yu, “Fortifying Taiwan: Security Challenges in the Indo-Pacific Era,” China Brief 24, no. 4 (February 16, 2024), https://jamestown.org/program/fortifying-taiwan-security-challenges-in-the-indo-pacific-era/.

[48] Marco Ho Cheng-Hui, “Civil Society Defense Initiatives,” China Brief 24, no. 4 (February 16, 2024), https://jamestown.org/program/civil-society-defense-initiatives/.

[49] Leo Blanken and Ben Cohen, “Reviving the Victory Garden: The Military Benefits of Sustainable Farming,” War on the Rocks, January 20, 2022, https://warontherocks.com/2022/01/reviving-the-victory-garden-the-military-benefits-of-sustainable-farming/.

[50] Patrick Griffin, “Contested Logistics: Adapting Cartel Submarines to Support Taiwan,” US Naval Institute Proceedings 150, no. 1 (January 2024), https://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/2024/january/contested-logistics-adapting-cartel-submarines-support-taiwan.

[51] Kush, The Rice Paddy Navy, 77, 164.

[52] David W. Hogan, U.S. Army Special Operations in World War II (Honolulu: University Press of the Pacific, 2004), 122.

[53] Max Hastings, Retribution: The Battle for Japan, 1944-45 (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2008), 207.

[54] Wei Wu T’Ien and Steven M. Goldstein, China’s Bitter Victory: The War with Japan, 1937-1945, ed. James Chieh Hsiung and Steven I. Levine (Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe, 1992), 88.

[55] Edward J. Drea, Japan’s Imperial Army: Its Rise and Fall, 1853-1945 (Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas, 2009), 214.

[56] Drea, 214.

[57] Mark Selden, China in Revolution: The Yenan Way Revisited (New York: Sharpe, 1995), 145.

[58] Hastings, Retribution, 346.

[59] Selden, China in Revolution, 145.

[60] U.S. Department of State, “Memorandum: Background on Situation in China,” Collection HST-PSF: President’s Secretary’s Files (Truman Administration), Foreign Affairs File, 1940-1953 (National Archives and Records Administration, July 31, 1946), 5, https://catalog.archives.gov/id/205716162.

[61] Drea, Japan’s Imperial Army, 261.

[62] “International Institutions Mobilize to Impose Accountability on Russia and Individual Perpetrators of War Crimes and Other Abuses,” American Journal of International Law 116, no. 3 (July 2022): 641, https://doi.org/10.1017/ajil.2022.29.

[63] “More than 307 thousand children have been evacuated to the Russian Federation from the territory of Ukraine, the DPR and the LPR since the end of February,” Interfax, June 18, 2022, https://www.interfax.ru/world/846957.

[64] Vicky Xiuzhong Xu, James Leibold, and Daria Impiombato, The Architecture of Repression: Unpacking Xinjiang’s Governance, Policy Brief No. 51 (Barton ACT, Australia: Australian Strategic Policy Institute, 2021), 53–54, https://www.aspi.org.au/report/architecture-repression.

[65] Bradley Jardine, Great Wall of Steel: China’s Global Campaign to Suppress the Uyghurs (Washington, DC: Wilson Center, 2022), 66.

[66] Joshua Silverstein, “Grand Strategies of the Great Powers: Churchill in World War I,” International Churchill Society, July 14, 2009, https://winstonchurchill.org/uncategorised/finest-hour-online-student-papers/grand-strategies-of-the-great-powers-churchill-in-world-war-i/.

[67] Hogan, U.S. Army Special Operations in World War II, 137.

[68] Mark D. Sherry, China Defensive (Washington, DC: Center of Military History, 1996), 24, https://history.army.mil/brochures/72-38/72-38.HTM.

[69] Saburō Hayashi and Alvin D. Coox, Kōgun: The Japanese Army in the Pacific War (Westport, CT: Greenwood press, 1978), 150.

[70] Hastings, Retribution, 201.

[71] Ben S. Malcom and Ron Martz, White Tigers: My Secret War in North Korea (Herndon, VA: Potomac Books, 2016), 26.

[72] John Arquilla, ed., From Troy to Entebbe: Special Operations in Ancient and Modern Times (Lanham, MD: University Press of America, 1996), 255.